Henry Lehman (Simon Russell Beale) is the first Lehman brother to arrive in America in epic play at Park Ave. Armory (photo by Stephanie Berger)

Park Ave. Armory, Wade Thompson Drill Hall

643 Park Ave. at 67th St.

Tuesday – Sunday through April 20

212-933-5812

www.armoryonpark.org

The prospect of sitting through a nearly three-and-a-half-hour play about the history of Lehman Brothers performed by a mere three actors might not necessarily be your idea of fun, but the US premiere of Ben Power’s adaptation of Stefano Massini’s Italian original is an epic masterpiece, must-see theater at its finest. Running in the massive Wade Thompson Drill Hall at the Park Ave. Armory through April 20 — advance tickets are sold out but a limited number of $45 rush tickets are available day of show — The Lehman Trilogy begins with a prologue in 2008 as a man packs boxes following the Black Thursday stock market crash on Es Devlin’s breathtaking set, a large, revolving transparent cube with several office-like rooms. Video designer Luke Halls projects geographic scenes onto the huge semicircle at the back of the stage and onto the floor around the cube, from the vast sea and plantation estates to cotton fields and the New York City skyline.

The first act, “Three Brothers,” quickly shifts to the past, to September 1844, with the arrival of twenty-one-year-old Henry Lehman (Simon Russell Beale) from his native Rimpar in Bavaria. He opens a small fabric store in Montgomery, Alabama, amid the plantations and is determined to live the American dream. “He left with an idea of America in his head / and got off the boat with America before him: / no longer in his mind but there in front of his eyes. / AMERICA. / Baruch HaShem,” Henry says about himself. Much of the play is related in poetic language spoken in the third person, interwoven with dialogue. Through it all, Candida Caldicot plays the piano just offstage, adding atmosphere and playful humor.

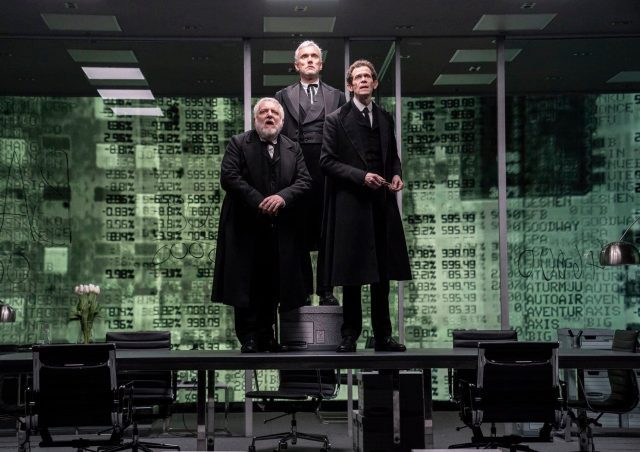

Henry (Simon Russell Beale), Emanuel (Ben Miles), and Mayer Lehman (Adam Godley) change the face of American capitalism in The Lehman Trilogy (photo by Stephanie Berger)

Henry is joined three years later by middle brother Emanuel (Ben Miles), who was twenty at the time, and then by nineteen-year-old Mayer Lehman (Adam Godley) in 1850; Henry is considered the head, Emanuel the arm, and Mayer the potato, an unequal partner sent to mediate any disputes between his older siblings. Henry has a brilliant mind for adapting to evolving market conditions, including inventing them in order to help the company flourish as it goes from selling fabrics to raw cotton, coffee, and coal to, ultimately, trading money itself once they move to New York City, setting up shop at 119 Liberty St. With each advance, they change their business sign, represented by writing the company’s new name on the glass wall. In the second act, “Fathers & Sons,” the next generation grows up and enters the organization: Emanuel’s son, Philip (Beale), and Mayer’s son, Herbert (Miles), who continue to expand the family’s holdings while getting further away from their heritage. “He was born in New York: / in his blood, not even a drop / of Germany or Alabama. / New Herbert. / Very new Herbert. / Son of New York, Herbert,” Mayer says. Act three, “The Immortal,” starts with a harrowing depiction of the suicides that came with the crash of 1929 as the more flashy Robert “Bobby” Lehman (Godley), Philip’s son, becomes the face of the company. Eventually, the firm runs out of Lehmans, instead being led by Pete Peterson (Beale) and Lewis Glucksman (Miles) as the 2008 mortgage crisis awaits.

Es Devlin’s set is another character in The Lehman Trilogy at Park Ave. Armory (photo by Stephanie Berger)

Power (Husbands and Sons, Medea) and Oscar-, Tony-, and Olivier Award–winning director Sam Mendes (The Ferryman, American Beauty) have streamlined Stefano Massini’s five-hour Italian original, which featured a much larger cast. Beale (Candide, Uncle Vanya), Miles (The Norman Conquests, Coupling), and Godley (Rain Man, Anything Goes) are a sight to behold, each onstage for nearly the entire play; they remain in Katrina Lindsay’s business-suit costumes, but it’s clear which of the many characters they are portraying at any given moment. Devlin’s cube is its own star, especially when, late in the show, it starts whipping around faster and faster, at speeds that will make you dizzy, never mind the three remarkable actors, who take it all in stride and as if they are one entity. The script doesn’t judge the Lehmans’ morality; it doesn’t mention that the Lehmans owned slaves in Alabama, and it avoids focusing on the ethical issues inherent in their rise to the heights of the financial world. “I don’t think I’m hated,” Bobby says, concerned about what his employees think of him. “No slave likes his master,” his wife, Ruth (Beale), says. “Am I the master?” Bobby asks.

The Lehman Trilogy also doesn’t turn the siblings into heroes or villains; each family member has his or her flaws and proclivities, and they become evident throughout the show, as does their genius when it comes to making money. It’s a riveting story of immigration and assimilation, with a particularly Jewish flavor as the Lehmans pave a path to fortune and wealth from a Bavarian shtetl to the cotton fields of the South and the golden streets of New York City. Henry touches the mezuzah and kisses his hand every time he enters and leaves his shop/office and often punctuates his desires by saying, “Baruch HaShem” (“Thank G-d”) — it’s as if his place of business is sacred ground, a holy temple — and the brothers sit shiva (a mourning ritual) whenever a family member passes. Although you know how it all ends in 2008, The Lehman Trilogy shines an absorbing light on just who the Lehman brothers were and how they made the most of their American dream.