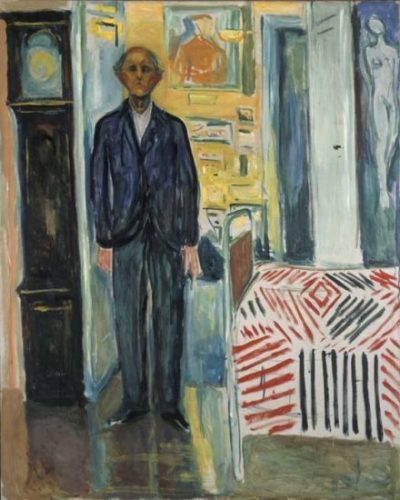

Edvard Munch, “Self Portrait between the Clock and the Bed,” oil on canvas, 1940–43 (© 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo © Munch Museum)

The Met Breuer

945 Madison Ave. at 75th St.

Tuesday – Sunday through February 4, suggested admission $12-$25

212-535-7710

www.metmuseum.org

The Met Breur’s exemplary exhibition “Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed” is anchored by the Norwegian artist’s remarkable “Self-Portrait between the Clock and the Bed,” which Munch worked on from 1940 to 1943. When the painting was completed, Munch was eighty; he passed away the following year. His last major self-portrait, it’s an exquisite reckoning of a man’s life. Munch pictures himself standing straight, eyes slightly closed, his hands at his sides. To his right is a grandfather clock that is a virtual doppelgänger for the artist, the round face and three sections mimicking Munch’s head, upper body, and legs. He knows his time is running out, and in true Munch style, he is none too happy about it, though seemingly resigned to his fate. To his left are representations of some of his other paintings as well as a bed with black and red cross hatches, which may be where he goes to sleep for the last time and never wakes up. The wide range of colors counterbalance the somber mood; this might be a kind of farewell from Munch, but it could be anybody facing mortality. At the beginning of his catalog preface “On Edvard Munch,” novelist Karl Ove Knausgaard writes, “‘My art has been an act of confession.’ So said Edvard Munch at the end of his life. I believe that anyone who has seen Munch’s paintings will understand that remark. Not only because he painted so many self-portraits, or because so many of the stock scenes he returned to again and again have clearly autobiographical elements, but because it’s as if something is revealed in everything he painted, even the landscapes without people, a field covered in snow, a jetty by the shore, a pine forest in the gloam. This is the essence of Munch’s art. But also what we can say least about.” Museumgoers will understand that and more after seeing the fifty works on view at the Breuer through February 4, several of which have never been shown publicly before and were part of Munch’s personal collection. “In fact,” Knausgaard (Out of the World, Min Kamp) continues, “the question is rather whether it is possible to say anything about the essence of Munch’s paintings at all. The paintings are wordless, they are silent and unmoving. They are made up of colors and shapes and they touch us in a way that words never can, they reach places in us where words have no access.”

Edvard Munch, “The Dance of Life,” oil on canvas, 1925 (Munch Museum, Oslo / © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

The exhibition is divided into seven sections whose titles alone capture the essence of Munch’s oeuvre: “Self-Portraits,” “Nocturnes,” “Despair,” “Sickness and Death,” “Puberty and Passion,” “Attraction and Repulsion,” and “In the Studio.” In the 1906 “Self-Portrait with a Bottle of Wine,” Munch sits in the foreground, looking contemplative and forlorn, his hands clasped in his lap, the loose brushwork placing him in an undetermined reality; he would suffer a nervous breakdown two years later. In two renditions of “The Sick Child,” Munch revisits the death of his beloved sister Sophie, who died from tuberculosis in 1877 at the age of fifteen; in the 1896 painting, Sophie is accepting of her fate, offering solace to her distraught mother, while the brushwork in the 1906 version, in which Munch layered paint and then scraped away color, creates an angrier, more expressionistic scene. Munch, who never married, explores sexuality and romance in “Madonna” and “The Kiss”; the former turns Jesus’s mother into a passionate woman, while the latter melds the two lovers’ faces into one. A lithographic crayon version of Munch’s most famous image, “The Scream,” features the handprinted text “I felt a loud, unending scream piercing nature”; nearby is a photograph of the Ljaborveien road that was the setting for the iconic work. The 1925 oil painting “The Dance of Life” is a more experimental version of the 1899–1900 original, depicting the three stages of a woman’s life as she ages — youthful in white, seductive in red, mourning in black — but it is also more dour despite the light glistening over the ocean. Other extraordinary pieces include “Sick Mood at Sunset: Despair,” “Moonlight,” “Puberty,” “Weeping Nude,” two versions of “The Artist and His Model,” “Death in the Sick Room,” and “The Night Wanderer,” which reveals Munch hunched over, unable to sleep, restless and uneasy, not knowing what to do and where to go next. “Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed” is an intense, emotional, deeply psychological journey into the abyss as portrayed by a supremely talented and innovative artist overwhelmed by mental anguish. (In Midtown, coinciding with the Met Breuer show, Scandinavia House has just extended “The Experimental Self: Edvard Munch’s Photography,” consisting of photographs, film, and prints, through April 4.)