Simon McBurney leads audiences deep into the Amazon in THE ENCOUNTER (photo © Joan Marcus 2016)

Golden Theatre

252 West 45th St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through January 8, $49 – $132

theencounterbroadway.com

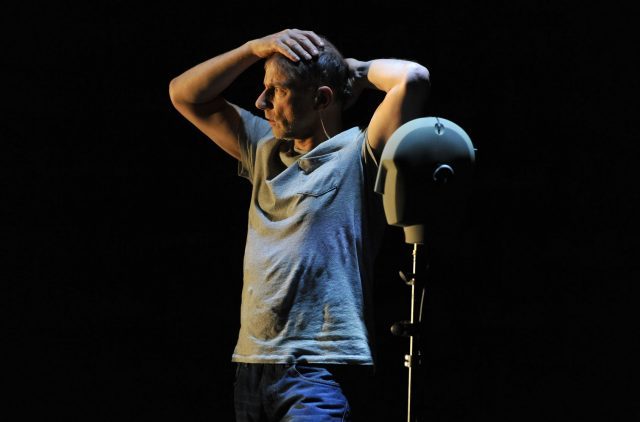

Innovative British theater director and actor Simon McBurney spent nearly twenty years trying to figure out how best to adapt the story of photojournalist Loren McIntyre’s adventures in the Amazon for the stage; what he ultimately came up with is absolutely genius. In the solo show The Encounter, playing at the Golden Theatre through January 8, McBurney uses the art of storytelling itself to dramatize McIntyre’s treacherous 1969 solo trip into Amazon’s Javari Valley, where he made contact with the indigenous Mayoruna tribe. Without any physical evidence, including photographs or notebooks, McIntyre shared his tale with Romanian-American writer Petru Popescu, whose book about the journey, Amazon Beaming, came out in 1991. And McBurney, whose 1999 production of Mnemonic by his Complicite company is considered a landmark in contemporary experimental theater, also uses the barest of evidence in The Encounter, which explores time, consciousness, memory, acculturation, and humanity’s connection with nature in spectacular ways. As the audience takes their seats, McBurney is wandering around the stage, which is littered with water bottles, a box of VHS tape, a desk with several microphones and a laptop, and a central figure — an Easter Island–like binaural head that turns out to be a speaker. McBurney addresses the crowd directly, toying with the notion of whether the show has actually started yet. “My children will always be able to look back over all of these photographs and videos and see their entire lives. But of course it’s not their life, it’s a story,” McBurney says about his smartphone. “So I’m worried about them mistaking it for reality, like we all mistake stories for reality. So I feel really responsible, because as I’m capturing moments on this [phone], I’m essentially deciding what story I’m going to tell them about their past . . . and about the world. But it’s not a reality. It’s a story. Stories are how we understand life. . . . You might say that stories are what have allowed the human race to thrive.”

Simon McBurney uses innovative technology to tell a fascinating story in one-man Broadway show (photo © Robbie Jack)

McBurney, who has appeared in such films as The Golden Compass, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, and Mission Impossible — Rogue Nation and has adapted such other literary works as Haruki Murakami’s The Elephant Vanishes, Bruno Schulz’s The Street of Crocodiles, and John Berger’s To the Wedding, tells his story through headphones that each audience member must wear, with different sound effects and dialogue coming out of the right and left earpieces. There are also sounds that reverberate through the theater, outside of the headphones, that immerse the audience into this created world, from doors slamming shut to random muttering voices. He calls it a “technological trick,” but it’s actually a shrewd artistic device that is no mere gimmick. McBurney plays multiple roles by using microphones that change the pitch, tone, and even accent of his voice while combining live text with prerecorded snippets; among the real-life characters he portrays are McIntyre, McIntyre’s pilot, and Popescu heard alongside dialogue from such psychiatrists, scientists, and other experts as Iain McGilchrist, Steven Rose, Marcus du Sautoy, George Marshall, and Rebecca Spooner, who lend authenticity to the proceedings. Meanwhile, McIntyre claims to communicate with members of the Mayoruna, including Beam, Barnacle, Tuti, and Red Cheeks, via some kind of telepathy that echoes McBurney’s use of the headphones for the audience. Meanwhile, he is sharing the story with his seven-year-old daughter, Noma. “Dadda, who are you talking to?” she asks early on. “I’m not talking to anybody, sweetie,” he replies. “Yes, you are!” she demands. “No, I’m not. Well, I am in a way,” he answers. “But there’s nobody there!” she claims. “That’s true, there’s nobody there,” he agrees. Of course, McBurney is talking about the show itself; the only person there is him, yet, as time goes on, we feel as if we are deep in the Amazon rainforest, meeting all of these characters, trudging through the muck, and seeing the monkeys that threaten McIntyre.

For both McIntyre and McBurney, the concept of time is a critical element, photographer and performer each trying to capture and share a moment in time. “What lay behind this frenzy, Loren thought, was fear. Fear of the future. Fear of losing the past,” McBurney relates. “So unlike these people, he thought. They never think of the future, they don’t hoard or store up belongings. Time for them was an invisible companion, something comfortable and unseen like the air. For us, the civilizados, time was a possession. An increasingly more efficient machine.” Time for the Mayoruna is changeable, while the West’s obsession with time is limiting and controlling. As McBurney writes in a new foreword to Popescu’s book, “Our adamantine vision of time as an arrow, moving in a pitiless irreversible horizontal motion towards oblivion, is called into doubt. Could it be that this version of time is a fiction, a story that only exists in our common imagination? Our idea of distance, crucially the distance between one person and another, is also challenged. The notion of a ‘separate self,’ so precious to our contemporary notion of identity, is undermined to the point that it becomes, for McIntyre, utterly illusory. One self, one so-called individual consciousness, he discovers, is not necessarily separated from another by language, time, or distance. We are possibly interconnected in ways to which we are, mostly, blind in the modern world — a world in which, paradoxically, we are more connected by technology that at any time in history.”

Simon McBurney makes remarkable use of unusual props in THE ENCOUNTER (photo by Joan Marcus)

The play, which runs approximately one hundred minutes without intermission, is also very much about contact, from McIntyre meeting the Mayoruna to how each audience member experiences it individually, a solitary yet communal experience. “There were so many things here in their elemental state, why not thought, too?” McBurney asks in the show. “Why not the simplest form of human contact — mind to mind. No, for goodness sake. But then something had been ratified, because he had been given this most beautiful gift.” We have also been given a most beautiful gift, The Encounter, which is essentially transmitted mind to mind in a mesmerizing tour de force by McBurney; also deserving of major kudos are set designer Michael Levine, sound designers Gareth Fry and Pete Malkin, lighting designer Paul Anderson, and projection designer Will Duke, who all participate in this amazing feat. At the end of the show, I fully believed that I had traveled through the Amazon with McBurney and McIntyre, had seen the Mayoruna, had felt the heat and fought off the mosquitoes, had experienced the fear and loneliness McIntyre had experienced, even though it was essentially all just McBurney getting inside my head and manipulating, and freeing, my mind. “To accept that our ability to hear, to listen to each other, is perhaps essential for our collective survival,” McBurney also writes in his foreword to Amazon Beaming. “These thoughts are urgent because, in order to survive, we need to acknowledge that there is another way of seeing the world and our place in it.” That could not be more true, today more than ever.