Bruce Conner’s A MOVIE is centerpiece of revelatory film exhibition and retrospective at MoMA

MoMA Film, Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53rd St. between Fifth & Sixth Aves.

September 16-30

Tickets: $12, may be applied to museum admission within thirty days

212-708-9400

www.moma.org

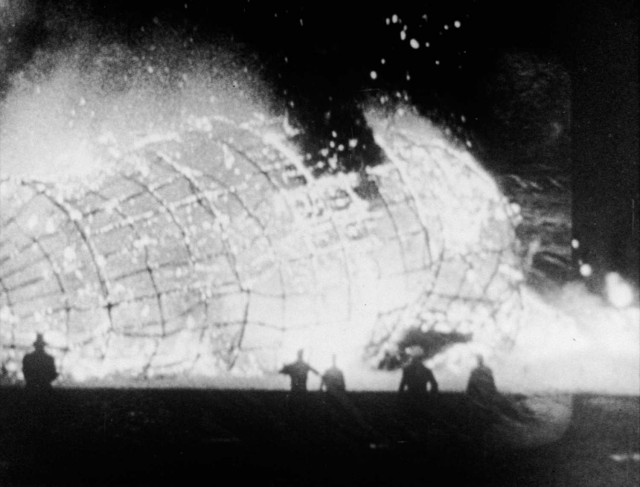

I first saw Bruce Conner’s seminal film A Movie in college, when I was studying with Amos Vogel, the Austrian-born founder of Cinema 16 and cofounder of the New York Film Festival. Conner’s 1958 twelve-minute marvel consists solely of found black-and-white footage edited into a fascinating tale of life on Earth in the post-WWII era, with an epic, boisterous soundtrack. “One of the most original works of the international film avant-garde, this is a pessimistic comedy of the human condition, consisting of executions, catastrophes, mishaps, accidents, and stubborn feats of ridiculous daring, magically compiled from jungle movies, calendar art, Academy leaders, cowboy films, cartoons, documentaries, and newsreels,” Vogel wrote in his 1974 book, Film as a Subversive Art, placing the film in his section about death. “Amidst initial amusement and seeming confusion, an increasingly dark social statement emerges which profoundly disturbs us on a subconscious level. . . . The entire film is a hymn to creative montage.” Watching A Movie can be a transformative experience; it was for me, showing me a whole new purpose behind filmmaking and leading me to further study cinema at NYU. So it’s fitting that A Movie is the first thing you see upon entering the MoMA exhibition “Bruce Conner: It’s All True,” a revelatory survey of Conner’s fifty-year career as a visual artist, including drawing, sculpture, photography, collage, photograms, performance, and, of course, film, continuing through October 2. It’s a stunning retrospective that ranges from his early “Ratbastard” hanging constructions to his obsession with the mushroom cloud and the atomic bomb, from his creepy “Child” sculpture to his punk-rock photographs for the music magazine Search and Destroy, from collages using found print materials to spectacularly detailed inkblot drawings, from his ghostly photograms using his own body to buttons declaring, “I Am Not Bruce Conner.” But at the center of it all are Conner’s films, scattered throughout the exhibition but also screening in the exciting film program “Movie in My Head: Bruce Conner and Beyond,” which runs September 16-30 and consists of nearly all of Conner’s cinematic output seen alongside work by many of his contemporaries.

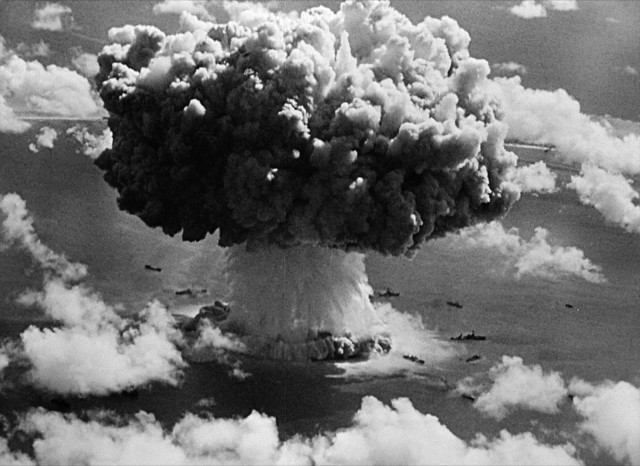

Toni Basil gets all groovy in Bruce Conner’s dazzling short film, BREAKAWAY, a precursor to the MTV video

A leading counterculture figure, Conner was born and raised in Kansas and spent most of his life in San Francisco, where he met up with the Beats, hippies, and punks; he died in 2008 at the age of seventy-five, leaving behind a legacy of cutting-edge short films that offer a unique look at America and its values, commenting on consumerism, war, religion, pop culture, and film itself — the mechanics of the medium, including the countdown leader and the physical filmstrips themselves, were often visible and part of the subject matter — in precisely edited works embedded with subliminal messages and featuring surprising soundtracks to match. “In my opinion, Bruce Conner is the most important artist of the twentieth century,” his friend, collaborator, and fellow native Kansan Dennis Hopper said. Hopper was on the set of Conner’s Breakaway with actor Dean Stockwell; Conner honored Hopper with the three-volume work “The Dennis Hopper One Man Show,” twenty-six collage etchings actually made by Conner. The MoMA exhibition includes that as well as Hopper’s photograph “Bruce Conner’s Physical Services” and Conner’s 1993 collage “Bruce Conner Disguised as Dennis Hopper Disguised as Bruce Conner at the Dennis Hopper One Man Show.” That’s all part of Conner’s modus operandi, where the art is more important than the artist, even though his hand is so evident in his works (although his name is often not). Breakaway is a frenetic short in which Antonia Basilotta, aka Toni Basil (later of “Mickey” fame), dances wildly in various black-and-white costumes (and naked) as Conner’s handheld camera keeps pace. Conner, considered by some (but not him) to be the father of MTV because of his editing style, also made videos for Devo (“Mongoloid”) and Brian Eno and David Byrne (“Mea Culpa,” “America Is Waiting”) in addition to Cosmic Ray, set to Ray Charles’s “What’d I Say.” Conner made two versions of Looking for Mushrooms, about his time in Mexico (and his search for psychedelic fungi), one silent, a later edit boasting the Beatles’ “Tomorrow Never Knows.” Two of his most political works are Report, which incorporates the Zapruder footage of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy with clips from advertising and industry films, and Crossroads, in which he repurposes the military’s Operation Crossroads film about the atomic bomb test at Bikini Atoll. And in 2008’s Easter Morning, Conner’s last completed major film, he reworks his 1966 Easter Morning Raga, creating a hypnotic compilation of abstract Kodachrome shots of nature set to Terry Riley’s “In C.”

CROSSROADS explores the Bikini Atoll atomic bomb tests, which fascinated Bruce Conner

“Movie in My Head: Bruce Conner and Beyond” begins with “Opening Night,” featuring A Movie and Conner’s Marilyn Times Five, which combines Marilyn Monroe’s performance of “I’m Through with Love” from Some Like It Hot with existing porn shots of a Marilyn look-alike, and Crossroads, introduced by chief curator Stuart Comer. Each program starts off with Conner’s Ten Second Film, a commissioned trailer for the 1965 New York Film Festival, under the leadership of Vogel, that was ultimately rejected for being too experimental. The series is arranged into eleven programs that encompass nearly all of Conner’s films along with works by Fernand Léger, Joseph Cornell, Carolee Schneeman, Christian Barclay, Stan Vanderbeek, William S. Burroughs, Robert Frank, Wallace Berman, Ron Rice, Cauleen Smith, Bruce Baillie, and others. On September 28, “Dreamland: An Evening with Peggy Ahwesh and Julie Murray,” the two filmmakers will show their own works along with Conner’s Take the 5:10 to Dreamland and Valse Triste, and on September 30, Michelle Silva of the Conner Family Trust will present “Revisitations,” consisting of rare and unfinished Conner films, shorts by George Kuchar and Ben Van Meter, and a talk with Brooklyn-based artist and archivist Andrew Lampert. The title of the MoMA series is taken from a 2003 interview in which artist Doug Aitken sat down with Conner for the nonprofit group Creative Time: “One of the reasons I made A Movie was because it’s what I wanted to see happen in film. Ever since I was fifteen years old, I’d been watching movies and thinking of ways to play with their storylines. For instance, I would imagine taking a backlit shot of Marlene Dietrich in Blonde Venus walking through a doorway and overlaying it with something like the final words from King Kong: ‘Beauty killed the beast.’ Then I’d imagine the next shot being something else entirely using different sound. Basically for years, I’d been playing with bits and pieces of different films in my head, and I kept assembling and reassembling this immense movie using pictures and sounds and music from all sorts of things. I’d been waiting for someone to come up with a movie like this. And nobody did.” So Conner did, as this MoMA exhibition and film series so effectively display.