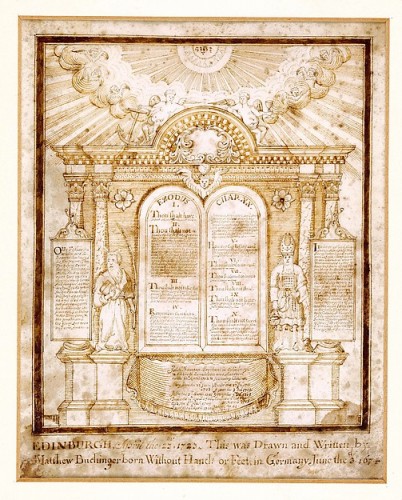

Matthias Buchinger, “Ten Commandments, personalized to John Thomson and family, merchant of Edinburgh,” ink on vellum, 1723 (collection of Ricky Jay)

The Met Fifth Avenue

Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Robert Wood Johnson Jr. Gallery, Gallery 690, second floor

1000 Fifth Ave. at 82nd St.

Daily through April 11, recommended admission $12-$25

212-535-7710

www.metmuseum.org

www.rickyjay.com

Amid all the excitement over the opening of the Met Breuer in the old Whitney space, it was possible to overlook what was going on at the museum’s longtime home base, now known as the Met Fifth Avenue. But it would be a shame if you missed “Wordplay: Matthias Buchinger’s Drawings from the Collection of Ricky Jay,” on view through April 11. In fact, you might have missed it even if you’ve been to the Met since January 8, when it opened in the long hallway gallery on the second floor. Magician, actor, curator, writer, consultant, television host, and conjurer Ricky Jay has been collecting works by the extraordinary German artist and performer Matthias Buchinger (1674–1739) for decades; nineteen pieces by Buchinger are included in the exhibition, alongside drawings, engravings, lithographs, etchings, books, and prints by Jasper Johns, Louise Bourgeois, Glenn Ligon, Cy Twombly, and various seventeenth- and eighteenth-century artists, placing Buchinger’s oeuvre in historical, artistic, and thematic context. Known as the Greatest German Living and the Little Man of Nuremberg, Buchinger was born in 1674 without hands, feet, or thighs, as he often noted on his works along with his signature. He reached only twenty-nine inches tall but led quite a life, marrying four times and having at least fourteen children by eight women before his death in 1739. Using the stumps of his arms, he created amazingly intricate drawings, from coats of arms to family trees to depictions of the Ten Commandments to portraits, incorporating calligraphy and micography, the latter an exquisitely detailed writing form in which tiny lines are actually made up of words. The Met provides magnifying glasses so you can fully experience such intricate works as “Ten Commandments, personalized to John Thomson and family, merchant of Edinburgh,” “Buchinger Family Tree,” “Coat of Arms, Norwich,” and the breathtaking pen and ink on vellum “Portrait of Queen Anne,” containing text from the Book of Kings, written even in the curls of her hair.

Anonymous, “Portrait of Matthias Buchinger,” engraving, 1707 (collection of Ricky Jay)

A relentless self-promoter, Buchinger described himself thusly: “This Little Man performs such wonders as have never been done by any but himself. He plays on various sorts of music to admiration, [such] as the hautboy, [a] strange flute in consort with the bagpipe, dulcimer and trumpet; and designs to make machines to play on almost all sorts of music. He is no less eminent for writing, drawing of coats of arms, and pictures to the life, with a pen; he also plays at cards and dice, performs tricks with cups and balls, corn and live birds; and plays at skittles or nine-pins to a great nicety, with several other performances, to the general satisfaction of all spectators.” The exhibition’s centerpiece is a gorgeous 1705 portrait of Buchinger, dressed in regal clothing, standing next to a writing desk and a rifle, a window behind him looking into the vast world beyond. Another highlight is Elias Baeck’s 1710 “Portrait of Matthias Buchinger Surrounded by Thirteen Vignettes,” celebrating all the different entertainments he performed. The show reveals that he was not alone; there are also portraits of several other artists from around the same time period who did not have arms or legs, including Thomas Inglefield, Johanna Sophia Liebschern, and Johannes Wynistorff, in addition to printed announcements of the skills of Miss Beffin and Martha Anne Honeywell. Even the title of the catalog, by Jay, is a treat: Matthias Buchinger: “The Greatest German Living”: By Ricky Jay, Whose Peregrinations in Search of the “Little Man of Nuremberg” are herein Revealed. A far-too-early 1722 elegy written for Buchinger states: “Buckinger’s gone, and quit this earthly Stage, / Who was the only Wonder of this Age; / This little Worthy, inwardly compleat, / His Soul inspired with celestial Heat, / Perform’d his Wonders with such artful Grace, / You’d judge him one of more than humane Race.” This exhibition displays his wonder and grace, as well as his fascinating humanity.