NYMPHOMANIAC: EXTENDED DIRECTOR’S CUT (Lars von Trier, 2013)

MoMA Film, Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53rd St. between Fifth & Sixth Aves.

Sunday, November 23, 2:30

Series runs through January 16

Tickets: $12, in person only, may be applied to museum admission within thirty days, same-day screenings free with museum admission, available at Film and Media Desk beginning at 9:30 am

212-708-9400

www.moma.org

www.magpictures.com

When I reviewed Lars von Trier’s Nymphomaniac earlier this year, when it was released in two separate “volumes,” I wrote, “I certainly would have preferred seeing Nymphomaniac in one complete sitting rather than in two parts, one of which stands head and shoulders above the other (although they do need each other); however, I’m not sure what I’ll do when the five-and-a-half-hour director’s cut is released later this year.” Well, as promised, the extended director’s cut is now available for viewing, being shown November 23 at 2:30 as part of MoMA’s annual series “The Contenders,” consisting of films the institution believes will stand the test of time. What follows is a slightly amended version of my initial review of the first two volumes; there are an additional thirty minutes added to the first part, while the second part now includes what MoMA refers to as “some of the most gruesome and wrenching passages ever seen on film.”

In Breaking the Waves, Danish Dogme 95 cofounder Lars von Trier’s 1996 breakthrough, Stellan Skarsgård plays a paralyzed man who convinces his wife (Emily Watson) to have sexual liaisons with other men and then tell him about the encounters in graphic detail. In von Trier’s latest controversial, polarizing work, Nymphomaniac, Skarsgård stars as Seligman, a single man who takes in a woman named Joe (Charlotte Gainsbourg) who is soon sharing her own sexual adventures with him, in extremely graphic detail. After finding Joe severely beaten in an alley, Seligman nurses her back to health while carefully listening to her life story. She repeatedly says she is a bad, irredeemable human being because of the things she has done, which started to go off the rails when she was a small child discovering the pleasure sensations to be had in her nether regions. Her sordid tale is told in flashbacks, as her younger self (Barking at Trees’ Stacy Martin) goes from lover to lover to lover to lover to lover ad infinitum. (The specific numbers are plastered over the screen.) Along the way, Seligman offers his own interpretation of her life, praising her sense of freedom while comparing her sexuality to fly-fishing, which von Trier (Dancer in the Dark, Melancholia, Antichrist) relates in a playful way that is at first absurdly silly but actually ends up coming together. Unfortunately, however, Martin is far too bland as Joe as she beds victim after victim, including Jerôme (a miscast Shia LaBeouf), perhaps the only one who truly loves her. The film also features Christian Slater and Connie Nielsen as Joe’s parents and Uma Thurman as a scene-stealing wronged wife.

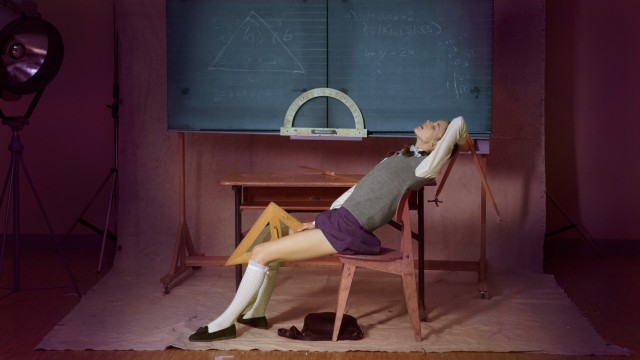

Joe (Charlotte Gainsbourg) continues her search for sexual pleasure and pain in the second half of NYMPHOMANIAC (photo by Christian Geisnaes)

The second half of von Trier’s four-hour graphic exploration of feminine sexuality and the very nature of storytelling itself is a masterfully crafted, often deadly dull and repetitive, but, in the end, gloriously inventive work. Joe (Charlotte Gainsbourg) is in the midst of telling her brutally in-depth tale of sexual addiction to the sincere and respectful Seligman (Stellan Skarsgård), who brought her into his home upon finding her badly beaten in a dark alley. In the flashbacks, Joe is now played with mystery and complexity by Gainsbourg, after the young Joe had been previously portrayed by the bland and boring Stacy Martin, and the change of actress is one of the key reasons why the second part works so much better than the first. Joe shares details of trying to make a sex sandwich, giving group therapy a shot, becoming obsessed with a violent sadist (Jamie Bell), and accepting a dangerous job with L (Willem Dafoe).

L (Willem Dafoe) offers Joe (Charlotte Gainsbourg) a dangerous job in controversial Lars von Trier sexual epic (photo by Christian Geisnaes)

In between her stories, which are divided into such chapters as “The Eastern and the Western Church (The Silent Duck)” and “The Mirror,” Seligman delves into various intellectual theories to help explain her exploits, discussing religion, paradox, democracy, language, mythology, Freud, and such dichotomies as suffering and happiness, pleasure and pain, Wagner and Beethoven, and the virgin and the whore. Cinematographer Manuel Alberto Claro’s camera is far more steady in these scenes, in contrast to the moving, handheld shots that dominate the flashbacks. The interplay between the calm, gentle Seligman and the lonely, lost Joe is beautifully acted and inherently touching, but, this being von Trier, the film’s ending will further controversies that already involve episodes of extreme violence and actual sexual penetration (the latter performed by body doubles). The MoMA series continues through January 16 with such other 2014 cinematic entries as Gillian Robespierre’s Obvious Child, Bennett Miller’s Foxcatcher, and Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash.