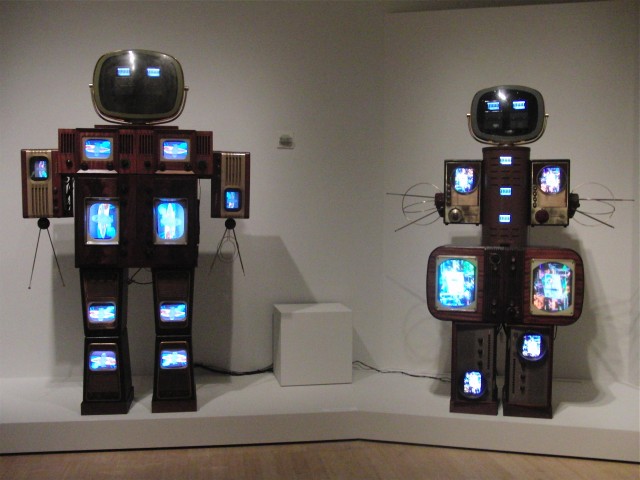

Nam June Paik, “Family of Robot: Father” and “Family of Robot: Mother,” single-channel video sculptures with vintage television and radio casings and monitors, tuner, liquid crystal display, color, silent, 1986 (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Asia Society Museum

725 Park Ave. at 70th St.

Tuesday – Sunday through January 4, $12, 11:00 am – 6:00 pm (free Fridays 6:00 – 9:00)

212-288-6400

www.asiasociety.org

www.paikstudios.com

I was on the subway late last week, reading one of the chapters in the “Nam June Paik: Becoming Robot” catalog for the splendid exhibition at Asia Society, when I looked up and saw an ad for a company that proclaimed, “The most powerful inventions are playful. . . . The most playful inventions are powerful,” touting a robot head, a remote pet feeder, and a synthar. The advertisement made me immediately think of the life and work of Paik, who instilled his highly technological, often futuristic sculptures, musical compositions, videos, drawings, installations, and live performances with an innate playfulness. If you’re not ready, willing, and able to have fun with the innovative, visionary Paik, then don’t bother going to Asia Society, because the exhibit, which continues through January 4, is nothing if not a whole lot of fun. The chapter I was reading on the subway was “Ok, Let’s Go to Blimpies: Talking about Nam June Paik,” a lively, informative, and, yes, playful discussion between museum director Melissa Chiu, former Paik studio manager Jon Huffman, former Paik studio assistant Stephen Vitiello, and Paik’s nephew, Ken Hakuta, that gets to the very essence of the international artist. Paik, who was born in Korea in 1932, moved to Hong Kong, studied in Japan, and lived and worked in Germany and New York, was way ahead of his time as he experimented with electronic music and images, television circuitry, and robots that could go to the bathroom, but with a unique, personal, warm touch that predated cell phones, social media, and interactive video games. “He wanted to redefine television [not as a] passive object, but [as] an object that we interact with,” Vitiello, who is a multimedia artist in his own right, says in the catalog. “We control our destiny. He was a humanist; he wanted to humanize everything, and technology was just a way of getting more time in which we could make better artwork, better software, have better lives.”

Nam June Paik, “TV Bra for Living Sculpture,” cello, two television sets, microphone, amplifiers, deflection coils, “fussbedienungsgerate,” cables, 1975 (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

The exhibition consists of more than five dozen sculptures, photographs, writings, videos, and other ephemera from throughout Paik’s career. The centerpiece is “Robot K-456,” Paik’s first automated, remote-control-operated, hermaphrotidic robot, which initially could poop beans. (It seems to have lost this function after being purposely hit by a car as part of a major 1982 show at the Whitney.) Also on display is “Family of Robot,” a mother, father, and baby created out of television monitors that blast images across their screens; “Golden Buddha,” a statue watching itself on television (and on which visitors can see themselves as well); “TV Chair,” which features a surveillance camera above and a monitor on the seat; a pair of antique television cabinets on which he has drawn over the surface; a robot brain in a glass dome; and “Three Camera Participation / Participation TV,” which gets a room unto itself, inviting everyone to see colorful, psychedelic projections of themselves in a far corner.

Nam June Paik, “Golden Buddha,” video installation with twenty-seven-inch monitor and closed circuit video camera, painted bronze Buddha with the artist’s additions in permanent oil marker, 2005 (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Perhaps most fascinatingly, “Becoming Robot” explores the artistic relationship between Paik and classically trained cellist Charlotte Moorman, who would play topless or wearing Paik’s “TV Bra for Living Sculpture” or “Light Bikini.” The show documents various performances, includes a room of many of Moorman’s outfits, and delves into her arrest for indecent exposure while playing Paik’s Opera Sextronique. Nudity also play a role in “Reclining Buddha,” a stone sculpture of a female Buddha relaxing on her side, right hand holding up her head in a classic pose, atop a pair of color monitors depicting a real naked woman in the same position; nearby is a collection of Paik’s decidedly childlike toys. And be sure to allow extra time to watch clips from Paik’s 1984 satellite installation, Good Morning, Mr. Orwell, a different kind of variety show with Moorman, Laurie Anderson, Peter Gabriel, Allen Ginsberg, Merce Cunningham, Philip Glass, and Joseph Beuys, as well as a sampling of Paik’s live performances. In his 1966 Great Bear Pamphlet, “Manifestos,” Paik declared, “Cybernated art is very important, but art for cybernated life is more important, and the latter need not be cybernated.” Eight years later, Paik coined the phrase “electronic superhighway.” As “Becoming Robot” so ably shows, Paik was at the crossroads of technology and culture long before the rest of us, predicting a world that would become obsessed with broadcasting personal information and images on handheld devices that resemble their own personal television stations. All the while, though, he remained philosophical and hopeful about the future, deeply serious about his work but intent on incorporating an intoxicating playfulness that is just plain fun — and decidedly human.