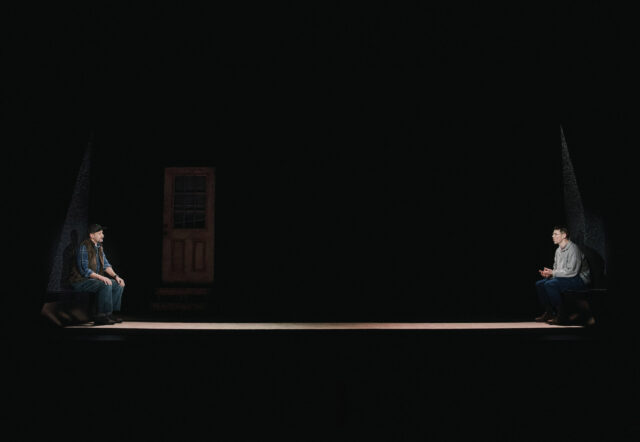

Paul Sparks and Brian J. Smith play half brothers facing a family crisis in Samuel D. Hunter’s Grangeville (photo by Emilio Madrid)

GRANGEVILLE

The Pershing Square Signature Center

The Alice Griffin Jewel Box Theatre

480 West 42nd St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through March 23, $69-$144

212-244-7529

www.signaturetheatre.org

In a short period of time, NYU grad Jack Serio has established himself as an exciting director of intimate dramas; since 2021, he has helmed Bernard Kops’s The Dark Outside at Theater for the New City, Rita Kalnejais’s This Beautiful Future at the Cherry Lane, Joey Merlo’s On Set with Theda Bara at the Brick, Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya in a Flatiron loft, and Ruby Thomas’s The Animal Kingdom in the Connelly’s tiny upstairs theater. His unique stagings foster particularly visceral connections with small audiences in these constrained spaces.

Since 2010, Idaho native Samuel D. Hunter has proved to be one of America’s most consistently thoughtful and intelligent playwrights, penning such poignant and involving works as A Bright New Boise, The Whale, Lewiston/Clarkston, Greater Clements, and A Case for the Existence of God, demonstrating an unfailing ear for dialogue while exploring the contemporary human condition.

The Signature has wisely teamed up Serio and Hunter for Grangeville, a moving and powerful story about a pair of estranged half brothers forced together when their mother becomes seriously ill.

The play opens in near darkness, with Jerry (Paul Sparks) sitting stage right, on a stoop in front of a door in the corner, and Arnold (Brian J. Smith) on a bench far away on the opposite side. The distance between them is palpable, and not only physically. Jerry, wearing a flannel shirt, vest, and baseball cap, looking like a down-on-his-luck farmer, is still living in Grangeville, the Idaho town the siblings — sired by different fathers — grew up in. Jerry and his wife are raising their two children there, and he’s also taken on the responsibility of caring for their ailing mother, who lives in a trailer park. (The costumes are by Ricky Reynoso, with lighting by Stacey Derosier and set design by dots.)

Jerry has called Arnold, a fashionably dressed queer artist living in Rotterdam with his husband, Bram, because their mother’s health bills are piling up and the money is running out. Rejected by the family because they would not accept his sexual orientation, Arnold has cut himself off from them, so he is surprised to get the call but even more shocked when he is told that their mother has named him executor in her will.

Arnold (Brian J. Smith) and Jerry (Paul Sparks) find themselves at a distance in gripping new play (photo by Emilio Madrid)

“That doesn’t make any sense!” Arnold argues. “I live in the Netherlands, we haven’t spoken in years! Why would she do this?!”

“Yeah, I mean when she had this drawn up she knew I was going through some — shit, so maybe she just figured you’d be better at this,” Jerry responds. “I mean you’re the smarter one! Maybe it’s a compliment!”

Jerry and their mother were counting on a supposed treasure she had bought on the cheap.

“She was convinced she found a long-lost piece of art by that famous artist — Jack something? Anyway, it’s this sculpture of a real tall skinny guy, all stretched out. Famous sculptor. Jack something,” Jerry explains.

“Wait — are you talking about Giacometti?” Arnold asks.

“That’s it. She was convinced that she found a long-lost Giacometti at this pawn shop in Burley,” Jerry answers.

“Okay, I — don’t know what to do with that,” Arnold says.

Over a brief period of time, the half brothers confront some of their personal failings and make unexpected admissions, but neither is anticipating any grand, sentimental rapprochements.

Serio expertly keeps the tension mounting without costume or set changes or dramatic narrative shifts, primarily only with dialogue. However, as the characters’ conversations switch from telephone to computer to in person — in one scene, Sparks becomes Bram, while in another, Smith is Stacey, his brother’s wife — the actors slowly get closer across the liminal space, eventually standing face-to-face, which packs a powerful punch. In addition, Chris Darbassie’s sound shifts with the changes in technology, at first high-pitched and squeaky, later clear and crisp.

Replacing the originally announced Brendan Fraser — who won an Oscar for starring in The Whale, the 2022 film adaptation of Hunter’s 2012 off-Broadway play — Emmy nominee Sparks (At Home at the Zoo, Grey House, Waiting for Godot) is sensational as Jerry, the ne’er-do-well older brother whose life is falling apart while he has no idea how to stop the avalanche. Every minor gesture, every movement is so carefully choreographed that the audience understands who Jerry is, not some mere country bumpkin with no future.

Tony nominee Smith (The Glass Menagerie, The Columnist, Three Changes) holds his own as Arnold, a conflicted man who has been harboring inner pain since he was a child and is not quite as grounded as he initially appears to be. Both men need help, the kind they never received from their parents or, sadly, from each other.

Jerry (Paul Sparks) and Arnold (Brian J. Smith) face off in Samuel D. Hunter’s Grangeville at the Signature (photo by Emilio Madrid)

But at the center of it all is Hunter’s razor-sharp, laser-focused language. There is not a word out of place, not a sentence that languishes in mediocrity. The story takes place in Grangeville, a town of approximately three thousand people in Idaho County, but it’s about America, with its troubled health-care system, rampant homophobia, fast-moving technology that leaves so many behind, and endless political battles between red and blue geographical locations as well as escalating issues over how we communicate with one another.

The play has a brutal yet subtle honesty as it reveals the dark underbelly of the American dream, laid to waste in the complexities of one family that refuses to blame the system.

“So what happened?” Arnold asks when Jerry explains that his decades-long marriage is in trouble.

“I think Stacey just — realized she wasn’t happy,” Jerry answers.

“What about you?” Arnold responds.

“Oh, I’ve never been happy. Heh,” Jerry admits matter-of-factly.

Arnold has not found happiness either, later telling his brother, “It’s like no matter what memory it is, no matter how seemingly innocuous it is, it always leads straight to shit. It’s like being stuck in a maze and no matter what path you choose there’s just black holes everywhere that you keep falling into.”

In Grangeville, there’s no escaping those black holes, no matter how far you try to run from them.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]