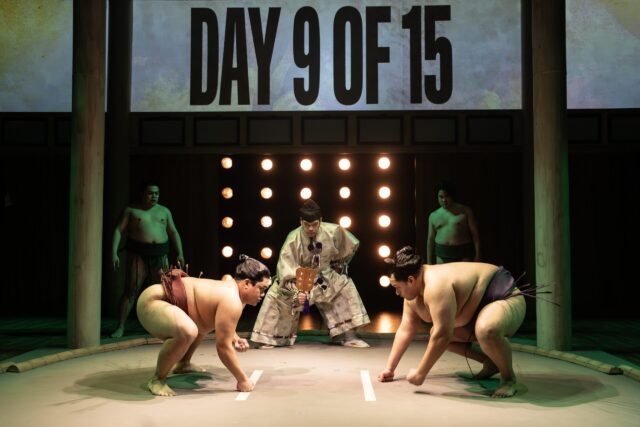

Wrestlers known as rikishi get ready to do battle in Lisa Sanaye Dring’s Sumo (photo by Joan Marcus)

SUMO

Anspacher Theater, the Public Theater

425 Lafayette St. at Astor Pl.

Tuesday through Sunday through March 30, $65-$93

212-539-8500

publictheater.org

Lisa Sanaye Dring’s Sumo takes audiences inside the ancient Japanese sport and sacred Shinto ritual of sumo, in which large-sized wrestlers known as rikishi do battle in a dohyo, or ring, attempting to push their opponent to the mat or out of the circle. Each competitor wears only a mawashi, or silk belt, around their waist, leaving little to the imagination, as they seek to climb the ladder of success through such san’yaku, or ranks, as the lower jonokuchi, jonidan, and sandanme to the higher sekiwake, ōzeki, and the ultimate yokozuna. Most matches are over in a few seconds, although some can last upwards of a minute.

The tense Ma-Yi Theater Company drama, which premiered in 2023 at La Jolla Playhouse and is now at the Public’s Anspacher Theater through March 30, is too long at two hours and twenty minutes (with intermission), and in its second act it gets caught up in treacly melodrama, but it is still a compelling exploration of dedication, honor, tradition, and respect in a sport Americans know little about, in a changing world that is redefining masculinity and conceptions about the human body.

Mitsuo (David Shih) is an ōzeki known as Kōryū, or Exalted Dragon, who runs a heya, or stable of wrestlers, that consists of the stalwart jūryō Ren (Ahmad Kamal), the makushita Shinta (Earl T. Kim), the sandanme Fumio (Red Concepción), the jonidan So (Michael Hisamoto), and the maezumo Akio (Scott Keiji Takeda), an overeager eighteen-year-old newcomer who is not ready to pay his dues, which includes sweeping up, remaining silent, and pouring tea before earning his way into the dohyo. A trio of kannushi, or Shinto priests (Kris Bona, Paco Tolson, Viet Vo), serve as a Greek chorus as well as the gyoji, or referees, and sponsors who scour the tournaments and practices deciding who they will bankroll.

Speaking directly to the audience early on, they explain, “Rikishi were once gods. Kami! Who fought for ownership of Japan. There were two deities: Takeminakata-no-Kami, god of wind and water, who fought on behalf of the humans. And Takemikazuchi-no-Kami, god of thunder, who fought on behalf of the divine. The imperial family supposedly descends from Takemikazuchi, and if Takeminakata had won instead of Takemikazuchi, Japan wouldn’t have been ruled for centuries by emperors and instead would have been governed by commoners — people like you. Ok, maybe not you.”

Mitsuo starts working Akio hard, seeing promise in him, which rankles the others, who nonetheless sneak in little lessons for Akio when no one else is around; they will be punished if Mitsuo catches them breaking the rules, which Akio doesn’t want to follow. “There is a saying: Before enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood, carry water,” So tells Akio, who shoots back, “I’m not here to be enlightened.” A moment later, So, explaining how good they all have it, adds, “In here, we are free. But you have to learn to trust us.”

The rikishi compete in a series of matches, employing such kimarite, or techniques, as harite (a slap), henka (a sidestep), and tachiai (initial charge); train in their heya, where no one else, especially women, are permitted; and, in the case of two of the men, grow extremely close. At one point Akio shares his doubts with Shinta, asking, “Do you think I can do this?” Shinta responds, “I have no idea. Can your body? Probably. It depends.” Akio: “On what?” Shinta: “On if the gods want it.” Akio: “Who?” Shinta: “Whoever you pray to.” Akio: “I don’t pray.” Shinta: “Yes you do.” Shinta poetically discusses what’s at the heart of sumo: “Our bodies are so big, so alive, that we wake everyone who sees. . . . It’s a service. It’s all an offering to her.” Akio repeats, “Her,” to which Shinta says, “Yes. The spirit of sumo is a woman.”

As the heya participates in several tournaments, friendships and relationships get tested and Akio needs to look deep inside himself to figure out who he truly is.

David Shih leads a strong cast in Lisa Sanaye Dring’s Sumo at the Public (photo by Joan Marcus)

Although I’ve never been to a wrestling or sumo tournament, I have seen several boxing bouts, sitting ringside as well as in the upper decks; unsurprisingly, the closer you are to the action, the more exciting it is. The same is true for Sumo; from my second-row aisle seat, I seemed to have a different experience from some of my colleagues, who were in the last row. Every foot stomp, or shiko, gave me a tingle. Wilson Chin’s dramatic set turns two of the Anspacher’s pillars into a prop around the dohyo; when the actors are not in the ring, they are practically in the audience’s lap.

Paul Whitaker’s lighting features five rows of nine lights behind sliding doors that open and close to indicate time and space changes. Hana S. Kim’s lively projections announce details of the matches on the back wall and floor, occasionally fitting neatly within the dohyo. Mariko Ohigashi’s costumes go beyond the miwashi to include elegant kimono, traditional gyoji wear, and contemporary clothing. Fabian Obispo’s sound design and original compositions enhance the atmosphere, setting the pace with Japanese hip-hop before the show and at intermission, blasting out such tunes as Denzel Curry’s “Sumo | Zumo,” ¥ellow Bucks’s “My Resort,” and Yuki Chiba’s “Dareda?”

Be prepared to see a lot of flesh; these are big men who might not win any bodybuilding contests but have sacrificed conventional notions of physical attractiveness for the cause, to be the best at what they do, knowing that when they are done, they will have trouble reconnecting to society, as this exchange details:

Shinta: You can’t leave.

So: I’ve given my whole body.

Fumio: There’s this pus that comes from my feet.

Shinta: Someone got my right ear — no more sound.

So: I miss my brothers.

Ren: We just do this.

Fumio: I could have learned to sail.

So: I have no skills.

Fumio: It’s just this.

Akio: How did you come here?

Fumio: My father trained me from when I was a boy.

Ren: Because my body needs it.

So: My family had too many mouths to feed.

Shinta: This was the path that opened before me, so I walked it.

Mitsuo: Because I’ve always been the best.

All: But only here.

Ren: And when I leave here /

Shinta: When I retire from here /

So: I’ll never leave here.

Fumio: When I get kicked out of here, I’ll be /

All: Screwed.

Akio: Then why do you do it?

Ren: Hatakikomi. Because I can.

Fumio: Tsuppari. Need.

Shinta: Tsuri-otoshi. Beauty.

So: Kote-nage. Devotion.

Mitsuo: Uwate-nage: You do it to win.

The strong cast is a mix of established actors, such as Shih (Once Upon a (korean) Time, KPOP) and Tolson (The Knight of the Burning Pestle, The Wind and the Rain), and performers making their New York City debuts; all handle themselves well, with a bonus nod to Kamal as Ren, perhaps the most complex of the characters. Shih-Wei Wu provides thrilling live taiko drumming throughout.

As the story continues, it occasionally resembles a special episode of Cobra Kai, the entertaining streaming series that is an extension of the Karate Kid movies, but while that show, in which Ralph Macchio and William Zabka reprise their 1980s roles, has its tongue in its cheek while dealing with teen issues, Sumo takes itself too seriously. Ultimately, Dring (Hungry Ghost, Kairos) and Obie-winning director Ralph B. Peña (The Romance of Magno Rubio, The Chinese Lady) paint themselves into a corner, throwing too much information at the audience and getting bogged down in exposition.

But that doesn’t mean there isn’t much to admire in the play, especially if you are sitting ringside.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]