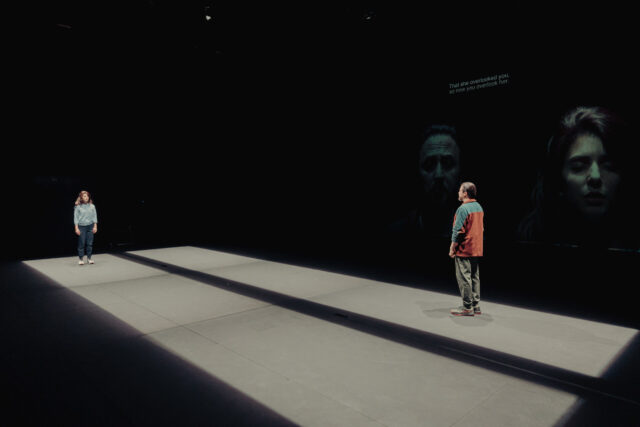

A woman (Ainaz Azarhoush) and her husband (Mohammad Reza Hosseinzadeh) contemplate freedom in Blind Runner (photo by Amir Hamja)

BLIND RUNNER

St. Ann’s Warehouse

45 Water St.

Tuesday – Sunday through January 24, $49-$69

stannswarehouse.org

utrfest.org

In September 2022, Iranian journalist Niloofar Hamedi was incarcerated for reporting on the controversial death of Mahsa Amini, a twenty-two-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman who died in a hospital shortly after being arrested for not wearing a hijab; the case was followed around the world. While in prison, Hamedi began running while her husband, Mohamad Hosein Ajoroloo, ran outside the building, preparing for a marathon. In June 2023, he told the New York Times, “Niloofar believes that enduring prison is like training for a marathon. Daily suffering. But imagining the joy of the finish line cancels out all the pain.”

That story, and others involving political imprisonments, served as inspiration for Iranian writer-director Amir Reza Koohestani’s haunting Blind Runner, continuing at St. Ann’s Warehouse through January 24 as part of the Under the Radar festival.

Éric Soyer’s set is a deep, dark area with two long, horizontal lines of light. At either side is a small camera, the projections of which appear on the large screen in back. The sublime video design is by Yasi Moradi and Benjamin Krieg, with stark lighting by Soyer, tense music by Phillip Hohenwarter and Matthias Peyker, and contemporary costumes by Negar Nobakht Foghani.

As the audience enters the space, actors Ainaz Azarhoush and Mohammad Reza Hosseinzadeh are already onstage, standing in concerned poses. Soon they each approach stanchions on opposite sides where they alternately write and erase such morphing phrases as “Based on a true story,” “Based on an actual story,” “Based on true history,” “Based on an actual history,” “Based on a factual history,” “Based on fiction history,” “Fact,” and “Fiction” before the husband concludes, “This is a theater.” Thus, we are instantly reminded that while what we are about to experience is artifice, it has been born out of fact, but whose facts? The playwright’s? The Iranian government’s? Ours in New York City, in America?

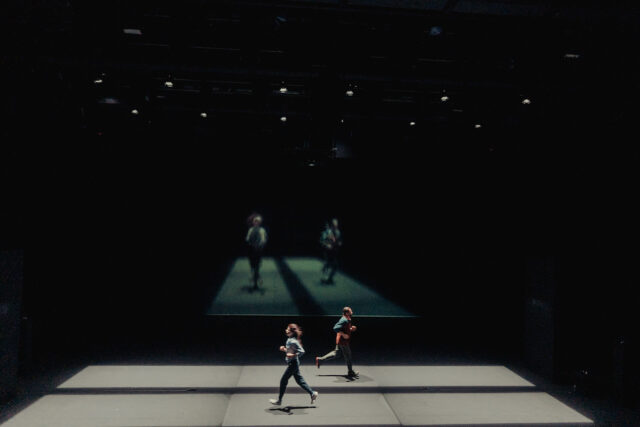

At first, the husband visits the wife once a week and they talk every day on the phone; in between their meetings, they run across the stage, each in a different strip of light, moving in opposing directions that signal the growing gap between them. She points out to him that everything they are saying and doing is being closely watched and recorded, like they are trapped in a spiderweb. While he values the visits and phone calls, she is becoming tired of them, as she has to carefully parse her words so as not to get him — or her — in trouble. This lack of communication frustrates him, since he wants to know the truth about how she is being treated and is adamant that he will get her released. “False hopes are worse than despair,” she admonishes.

Running is at the center of Amir Reza Koohestani’s Blind Runner at St. Ann’s Warehouse (photo by Amir Hamja)

He asks her, “Why don’t you just give me a ring to say that you’re fine?” She quickly answers, “Why should I lie?”

At her request, he meets with a blind marathoner named Parissa (Azarhoush) who lost her sight during a political protest and wants him to be her guide runner for an upcoming competition in Paris. He is apprehensive about it, but his wife thinks it is a good opportunity. “It’s not just running,” he explains. “It’s a matter of rhythm. You need to be in sync together.”

It’s clear he is not just talking about his potential professional relationship with Parissa, especially when his wife is not worried that he his traveling to Europe with another woman as the contentious Illegal Migration Bill is about to be passed in England.

Presented by the Mehr Theatre Group in Persian with English supertitles, the sixty-minute Blind Runner is a bleak, mysterious, and deeply involving play about the physical, psychological, and emotional choices we make as individuals and as a society and the consequences that result. Justice around the world can be blind, but the answer is not running away, or remaining silent, even as the risks grow and private and public freedom is jeopardized.

Koohestani himself started running after the Green Movement in Iran was suppressed, an activity he considered “an alternative to the demonstrations that were no longer being held and the freedom that had left us again for the umpteenth time,” he writes in a program note. His hypnotic play, also inspired by the case of imprisoned student activist Zia Nabavi, captures that feeling, with its hard-hitting dialogue and striking visuals that zoom in on the characters’ faces and merge their bodies when they are running, leading to a powerful conclusion. It is sometimes difficult to know where to look — at the two actors, at their projections on the screen, or at the supertitles above — but Azarhoush and Hosseinzadeh deliver beautifully human performances that ground the narrative.

In conjunction with Blind Runner, St. Ann’s is hosting the exhibition “Unseen Iran: A Celebration of Iranian Art & Culture,” featuring works by Tahmineh Monzavi (street photography), Shirin Neshat (the Villains triptych and Divine Rebellion related to the Arab Spring riots), Bahar Behbahani (Warp and Woof from her “Through a Wave, Darkly” series ), and Safarani Sisters (the video painting Awake) in addition to a Persian Tea Room where you can sip tea and relax before the show.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]