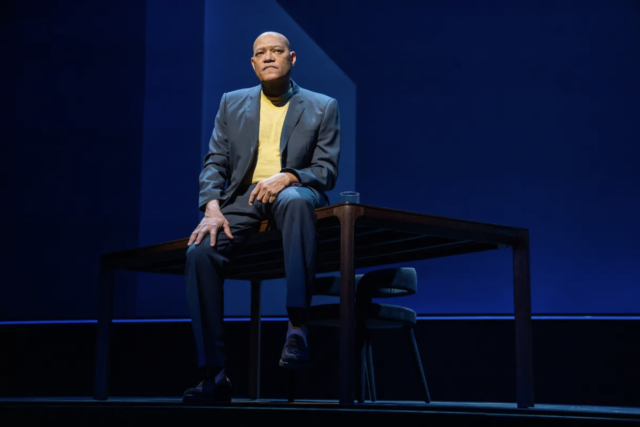

Laurence Fishburne debuts one-man show at PAC NYC (photo by Joan Marcus)

LIKE THEY DO IN THE MOVIES

Perelman Performing Arts Center (PAC NYC)

251 Fulton St.

Through March 31, $64-$158

pacnyc.org

I’ve been closely following the career of Laurence Fishburne since I saw Apocalypse Now when it premiered at the Ziegfeld in the summer of 1979, paying an exorbitant five bucks for a ticket and a special program. Fishburne, who was fourteen when filming got underway, played Mr. Clean, a crew member from the Bronx aboard a Navy river patrol boat heading up the Nùng River on a dangerous secret mission during the Vietnam War. On June 2, 1992, I was at the Walter Kerr Theatre, seeing August Wilson’s Two Trains Running, its first show since Fishburne had won a Tony for Best Performance by an Actor in a Featured Role in a Play two days earlier, only the second Black man to earn that honor, following Zakes Mokae in Master Harold . . . and the Boys ten years earlier. I am not a fan of entrance applause, but that night Fishburne was greeted with one of the longest and loudest ovations I’ve ever been a part of.

So I had high expectations for the world premiere of his one-man show, Like They Do in the Movies, continuing at PAC NYC through March 31. In the nearly two-and-a-half-hour presentation (including intermission), Fishburne once again displays his vast talents as a compelling storyteller; his resume consists of more than 130 film, television, and stage appearances, with five Emmys, the Tony, and an Oscar nomination to his credit.

The show gets off to a terrific beginning as Fishburne, in a black sequined dress and hood, introduces himself after a projection of dozens of his films flash past on a large rectangular screen behind him. He calls his acting career “a polite way of saying I’ve been a bullshit artist all my life.” He then tells the audience that he is going to share a series of stories in which “some are true, some pure fiction, and some are a mix of both.”

Amiable and warm, Fishburne starts by recounting his childhood; he was born in Augusta, Georgia, on July 31, 1960, and later moved to Brooklyn. His mother, Hattie Bell Crawford, was an eccentric character who operated a charm school in their home; his father, known as Big Fish, was a corrections officer and womanizer. Fishburne relates tales about his parents and grandparents as photographs of them appear on the screen. He describes his mother as having narcissistic personality disorder type 2 and says that she was sexually abusive toward him. He ends numerous deeply personal anecdotes by promising, “More about that later.” Alas, that is not always the case.

The center section, which makes up the bulk of the play, comprises five long tales that seem to have been told directly to Fishburne or that he witnessed. He enacts them in exquisite detail, performing multiple roles with great skill and changing costumes, from a casual blazer and slacks to a lush caftan to an ill-fitting sweater and street clothes. No costume designer is credited, so perhaps the duds come from his own closet.

Each of the vignettes, which might or might not be completely true, is engrossing. A tough-talking ex-con named Fitzpatrick who works for the Daily News impersonates a cop on the subway. A homeless man discusses his plans for the future as he washes cars. A lawyer wants to get his family out of New Orleans as Katrina hits but his wife, an OB/GYN nurse, has three patients ready to give birth. A retired policeman rambles on as he attempts to keep fans away from Fishburne while the actor is taking a break on a movie set. And a British ex-pat explains how he is not a pimp as he offers Fishburne his choice of women at an Australian bordello.

Director Leonard Foglia (Thurgood, which earned Fishburne a Best Leading Actor Tony nomination for his portrayal of Thurgood Marshall) keeps Fishburne moving about on Neil Patel’s set, which contains a few chairs and a table that are reconfigured for each segment. Elaine J. McCarthy’s projections display photographic backdrops helping identify locations. Tyler Micoleau’s lighting and Justin Ellington’s sound, with interstitial clips from jazz, R&B, gospel, and rock songs, are on target.

As well done as the scenes are, they don’t lend insight into Fishburne’s own character, his real self; the Australian anecdote is particularly disconcerting as the audience wonders whether Fishburne is relating an actual experience he had at a brothel.

He then returns to his personal narrative, delving into several startling family revelations and his parents’ late-in-life illnesses. He doesn’t talk about his career, and he says nothing about his partners and mentions his son Langston only once. (Fishburne has been divorced twice and has three children.) We already know that Fishburne is one of the best American actors of his generation, through his myriad outstanding performances; we want to learn more about him as an individual, as a human being, especially after he teases us in the first act. He doesn’t tie up enough loose ends, which is of course his prerogative, but days after I saw the play, I’m still wanting more. I had a similar experience at John Lithgow’s 2018 solo show, Stories by Heart, in which too much time was spent on his reenacting — brilliantly — two short stories that his father would read to him and his siblings.

In the program, Fishburne thanks Whoopi Goldberg, John Leguizamo, and Anna Deavere Smith for “showing me the way.” That trio of stalwart solo performers have mastered going between autobiography and exploring the state of contemporary culture and politics. Fishburne is eminently likable and riveting, but Like They Do in the Movies might have benefited from a better balance of the two.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]