Godzilla emerges from the ocean after nuclear testing in classic monster movie

JAPANESE HORROR

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

Through March 14

212-727-8110

www.filmforum.org

Wanna see something really scary? Then head over to Film Forum to see at least one of the two dozen fright flicks comprising “Japanese Horror,” continuing through March 14. No one makes scary movies like the Japanese do, and this series has a great mix of films as we spiral into an election year. You can’t go wrong with any of them; below is only some of the awesomeness. Also on the schedule are Ishirô Honda’s Mothra, Masahiro Shinoda’s Demon Pond, Teruo Ishii’s Horrors of Malformed Men, Mitsuo Murayama’s The Invisible Man vs. the Human Fly, and Kaneto Shindô’s Onibaba, among others.

THE FACE OF ANOTHER (TANIN NO KAO) (Hiroshi Teshigahara, 1966)

Wednesday, March 6, 6:30

filmforum.org

Kôbô Abe and director Hiroshi Teshigahara collaborated on five films together, including the marvelously existential Woman of the Dunes in 1964 and The Face of Another two years later. In the latter, Tatsuya Nakadai (The Human Condition, Kill!) stars as Okuyama, a man whose face has virtually disintegrated in a laboratory accident. He spends the first part of the film with his head wrapped in bandages, a la the Invisible Man, as he talks about identity, self-worth, and monsters with his wife (Machiko Kyo), who seems to be growing more and more disinterested in him. Then Okuyama visits a psychiatrist (Mikijirô Hira) who is able to create a new face for him, one that would allow him to go out in public and just become part of the madding crowd again. But his doctor begins to wonder, as does Okuyama, whether the mask has actually taken control of his life, making him as helpless as he was before. Abe’s remarkable novel is one long letter from Okuyama to his wife, filled with utterly brilliant, spectacularly detailed examinations of what defines a person and his or her value in society.

Abe wrote the film’s screenplay, which tinkers with the time line and creates more situations in which Okuyama interacts with people; although that makes sense cinematically, much of Okuyama’s interior narrative, the building turmoil inside him, gets lost. Teshigahara once again uses black and white, incorporating odd cuts, zooms, and freeze frames, amid some truly groovy sets, particularly the doctor’s trippy office, and Tōru Takemitsu’s score is ominously groovy as well. As a counterpart to Okuyama, the film also follows a young woman (Miki Irie) with one side of her face severely scarred; she covers it with her hair and is not afraid to be seen in public, while Okuyama must hide behind a mask. But as Abe points out in both the book and the film, everyone hides behind a mask of one kind or another.

Reiko Asakawa (Nanako Matsushima) finds herself and her young son in danger in Ringu

RINGU (Hideo Nakata, 1998)

Thursday, March 7, 7:20

filmforum.org

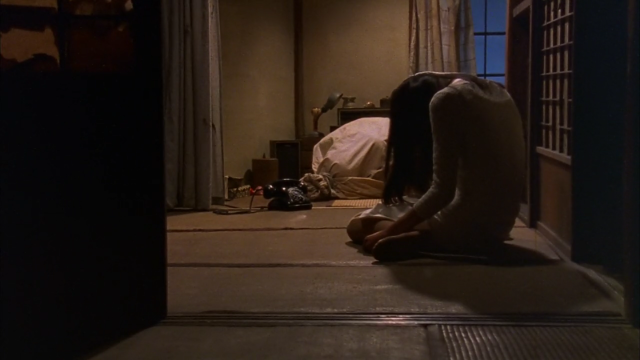

In many ways, Hideo Nakata’s 1998 classic, Ringu, is the ultimate horror movie: a film about a film that scares people to death. But Ringu is not chock-full of blood, gore, and violence; instead it’s more of a psychological tale that plays out like an investigative procedural as two characters desperately search for answers to save themselves from impending death.

Journalist Reiko Asakawa (Nanako Matsushima) and her ex-husband, professor and author Ryūji Takayama (Hiroyuki Sanada), are both on tight deadlines — for their lives. After Reiko’s niece, Tomoko Ōishi (Yuko Takeuchi), suddenly dies, apparently from fright, Reiko discovers a rumor that Tomoko and some of her friends had watched a short video, then received a phone call in which an otherworldly voice told them they would die in a week. And they did.

Reiko tracks down the eerie videotape and watches it herself — a few minutes of creepy, hard-to-decipher grainy images — after which the phone rings, telling her she has one week to live. She shows the tape to Ryūji, who has extrasensory powers, and they start digging deep into who shown in the tape and what it is trying to communicate. As they begin uncovering fascinating facts, their son, Yōichi (Rikiya Ōtaka), gets hold of the video and watches it, so all three are doomed if they don’t figure out how to reverse the curse — if that is even possible.

Adapted by screenwriter Hiroshi Takahashi from the 1991 novel by Koji Suzuki, Ringu is a softer film than you might expect, maintaining a slow, even pace, avoiding cheap shocks as the relatively calm and gentle Reiko continues her research and is able to work together with her former husband, who has not been a father to Yoichi at all. The film gains momentum as Reiko and Ryūji learn more about the people in the video, but Nakata, who went on to make several sequels in addition to Dark Water, Chaos, The Incite Mill, and the Death Note spinoff L: Change the World, never lets things get out of hand. The supporting cast includes pop singer Miki Nakatani as Mai Takano, one of Ryūji’s students; the prolific Yutaka Matsushige (he’s appeared in more than one hundred films and television shows since 1992) as Yoshino, a reporter who assists Reiko; and Rie Inō as the strange figure hiding behind all that black hair. Oh, and just for the record, a “homomorphism” — the word is written on Ryūji’s blackboard of mathematical equations — is a map between algebraic objects that come in two forms, “group” and “ring,” the latter being a structure-preserving function.

A black cat is not happy with the turn of events in Kaneto Shindô’s Kuroneko

KURONEKO (藪の中の黒猫) (Kaneto Shindô, 1968)

Thursday, March 7, 12:30

Monday, March 11, 7:40

Thursday, March 14, 9:10

filmforum.org

“A cat’s nothing to be afraid of,” a samurai (Rokkô Toura) says in Kaneto Shindô’s 1968 Japanese horror-revenge classic, Kuroneko. Oh, that poor, misguided warrior. He has much to learn about the feline species but not enough time to do it before he suffers a horrible death. In Sengoku-era Japan, a large group of hungry, bedraggled samurai come upon a house at the edge of a bamboo forest. Inside they find Yone (Nobuko Otowa) and her daughter-in-law, Shige (Kiwao Taichi), whose husband, Hachi (Kichiemon Nakamura), is off fighting the war. The men viciously rob, rape, and murder the women, but they leave behind a mewing black cat (“kuroneko”) that is not exactly happy with what just happened. Three years later, the aforementioned samurai is riding his horse on a dark night when he encounters, by the Rajōmon Gate, a young woman positively glowing in the darkness. She says she is frightened and asks if he can accompany her home; he claims he has met her before but can’t quite place her. He agrees to help her, and when they reach her abode he is treated to some tea served by an older woman and some fooling around with the younger one — until the latter creeps on top of him and turns into a menacing animal, biting into his throat and drinking his blood. One by one, the samurai are lured into this trap, until a surprise warrior arrives.

A bamboo forest leads to a kind of hell for samurai in Kuroneko

Written and directed by Shindô and based on an old folktale, Kuroneko is a tense, spooky film, with a foreboding score by Hikaru Hayashi (Shindô’s The Naked Island and Onibaba) and shot in eerie black-and-white by Kiyomi Kuroda (Shindô’s Mother, Human, and Onibaba). One of the great feminist ghost stories, it’s like the missing sequel to Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan, with elements of Akira Kurosawa’s Hidden Fortress and Rashomon thrown in, along with echoes of flying ninja movies. Memorable images abound: The two women, in ghostly white, float in the air; the camera weaves through the bamboo forest; a gruesome killer is beheaded. The film also features Kei Satō as Raiko, Hideo Kanze as Mikado, and Taiji Tonoyama as a farmer, but Kuroneko belongs to Shindô regular — and his lover and, later, his wife — Otowa, who appeared in nearly two dozen of his films, and Taichi, who also worked with such other directors as Keisuke Kinoshita, Mitsuo Yanagimachi, Yôji Yamada, and Shintarô Katsu before dying in a car accident in 1992 at the age of forty-eight. The two women go about their business with a calm and somewhat placid demeanor until they pounce, like cats luring mice to certain doom.

Nobuhiko Obayashi’s wild and crazy Hausu has to be seen to be believed

HOUSE (HAUSU) (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977)

Friday, March 8, 2:40

Tuesday, March 12, 7:00

Wednesday, March 13, 2:20

filmforum.org

Japanese experimental filmmaker Nobuhiko Obayashi’s House (Hausu) is one of the craziest movies ever made; the 1977 cult classic took more than three decades to get its U.S. theatrical release, but it’s been a must-see ever since. Truly one of those things that has to be seen to be believed, House is a psychedelic black horror comedy musical about Gorgeous (Kimiko Ikegami) and six of her high school friends who choose to spend part of their summer vacation at Gorgeous’s aunt’s (Yoko Minamida) very strange house. Gorgeous, whose mother died when she was little and whose father (Saho Sasazawa) is about to get married to Ryoko (Haruko Wanibuchi), brings along her playful friends Melody (Eriko Ikegami), Fantasy (Kumiko Oba), Prof (Ai Matsubara), Sweet (Masayo Miyako), Kung Fu (Miki Jinbo), and Mac (Mieko Sato), who quickly start disappearing like ten little Indians.

House is a ceaselessly entertaining head trip of a movie, a tongue-in-chic celebration of genre with spectacular set designs by Kazuo Satsuya, beautiful cinematography by Yoshitaka Sakamoto, and a fab score by Asei Kobayashi and Mickie Yoshino. The original story actually came from the mind of Obayashi’s eleven-year-old daughter, Chigumi, who clearly has one heck of an imagination. Oh, and we can’t forget about the evil cat, a demonic feline to end all demonic felines. The film was released in 2009 prior to its appearance on DVD from Janus, the same company that puts out such classic fare as Federico Fellini’s Amarcord, Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon, Jacques Tati’s M. Hulot’s Holiday, François Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player, Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game, and Jean-Luc Godard’s Vivre sa Vie, so House has joined some very prestigious company. And who’s to say it doesn’t deserve it?

Ishirō Honda has a smoke with his atomic-gas-breathing monster on the set of Godzilla

GODZILLA (Ishirō Honda, 1954)

Friday, March 8, 4:40

Tuesday, March 12, 4:50

filmforum.org

More than two dozen sequels, prequels, remakes, and reboots have not diluted in the slightest the grandeur of the original 1954 version of Godzilla, one of the greatest monster movies ever made. If you’ve only seen the feeble, reedited, Americanized Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, made two years later with Canadian-born actor Raymond Burr inserted as an American reporter, well, wipe that out of your head. On March 8 and 12, Film Forum is screening the real thing, the restored treasure as part of “Japanese Horror.” The film was inspired by Eugène Lourié’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and a real incident involving the Daigo Fukuryū Maru, a tuna-fishing boat that got hit by radioactive fallout in January 1954 from a U.S. test of a dry-fuel thermonuclear device in the Pacific Ocean. Writer-director Ishirō Honda and cowriter Takeo Murata expanded on Shigeru Kayama’s story, focusing on a giant dinosaur under the sea who comes back to life after H-bomb testing by the U.S.

Standing 165 feet tall and able to breathe atomic gas, Godzilla — known as Gojira in Japanese, a combination of gorira, the Japanese word for gorilla, and kujira, which means whale — wreaks havoc on Japanese towns as he makes his way toward Tokyo. While the military and the government want to destroy the creature — who is played by Haruo Nakajima and Katsumi Tezuka in a monster suit, tramping over miniature houses, streets, cars, trains, and buildings using the suitmation technique (both men also make cameos outside the costume) — Dr. Yamane (Takashi Shimura) wants to study Godzilla to find out how the radiation only makes it stronger instead of destroying it. (Throughout, Godzilla is referred to as “it” and not “he,” perhaps because the creature is in part a representation of America and what it wrought in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.) “Godzilla was baptized in the fire of the H-bomb and survived. What could kill it now?” Dr. Yamane asks. Meanwhile, one of Dr. Yamane’s assistants, Dr. Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata), is working on a secret oxygen destroyer that he will show only to his fiancée, Yamane’s daughter, Emiko (Momoko Kōchi), who is having trouble telling Dr. Serizawa that she is actually in love with salvage ship captain Hideto Ogata (Akira Takarada). “Godzilla’s no different from the H-bomb still hanging over Japan’s head,” Ogata tells Dr. Yamane, who is none too pleased with his take on the situation. Through it all, the media risks everything to get the story.

Even for 1954, many of the special effects, photographed by Masao Tamai, are cheesy but fun, and composer Akira Ifukube’s fiercely dramatic score goes toe-to-toe with the monster. The Toho film is no mere monster movie but instead is filled with metaphors and references about WWII and the use of atomic bombs, examining it from political and socioeconomic vantage points while questioning the future of technological advances. “But what if your discovery is used for some horrible purpose?” Emiko asks Dr. Serizawa, who wears an eye patch, as if he can only see part of things. Godzilla could only have come from Japan, much like King Kong was purely an American creation produced by Hollywood; in fact, the two went at it in Honda’s 1962 film, King Kong vs. Godzilla. The next year, Akira Kurosawa would make I Live in Fear (Ikimono no kiroku), an intense psychological drama about the nuclear holocaust’s effects on one man, a factory owner played by Toshirô Mifune — who meets with a dentist portrayed by Kurosawa regular Shimura — a kind of companion piece to Godzilla. Honda, who served as an assistant director to Kurosawa on many films before making his own pictures, would go on to make such other sci-fi flicks as Rodan, The H-Man, Mothra, and Destroy All Monsters, but it was on Godzilla that he got everything right, capturing the fate of a nation in the aftermath of nuclear devastation while still managing to gain sympathy for the monster. It is also difficult to watch the film today without thinking of America’s current debate over illegal immigration and fear of the other, particularly when Godzilla approaches an electrified fence meant to keep him out, as well as the threat of nuclear war.

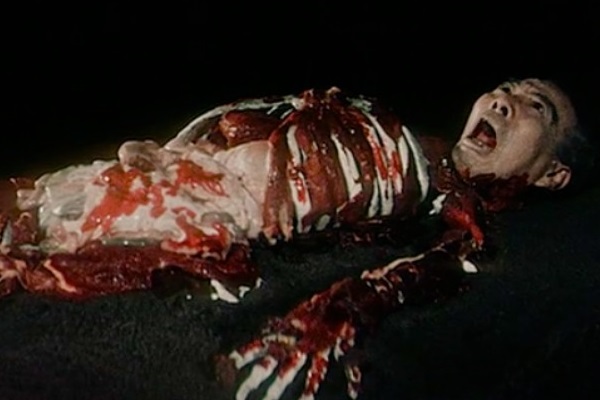

Shirō Shimizu (Shigeru Amachi) is trapped in the realms of hell in Nobuo Nakagawa’s awesome Jigoku

JIGOKU (THE SINNERS OF HELL) (Nobuo Nakagawa, 1960)

Saturday, March 9, 9:10

Wednesday, March 13, 12:15 & 6:30

filmforum.org

Nobuo Nakagawa’s Jigoku is a dark, demonic masterpiece, a descent into the deepest circles of hell, where sinners face the swirling vortex of torment and rivers of pus and blood. Jigoku goes places that would make even Dante and Hieronymus Bosch turn away in fear while Roger Corman and Mario Bava rejoice. In the film, seemingly everyone theology student Shirō Shimizu (Shigeru Amachi) comes into contact with dies a tragic death. He and Yukiko Yajima (Utako Mitsuya) become engaged, but their lives change forever when Shirō and his friend Tamura (Yōichi Numata), a sociopath of pure evil, go for a ride and Tamura, behind the wheel, runs over gangster Kyōichi “Tiger” Shiga (Hiroshi Izumida) and drives away, showing no remorse whatsoever, reminiscent of Artie Strauss (Bradford Dillman) and Judd Steiner (Dean Stockwell) in Richard Fleischer’s Compulsion. However, Kyōichi’s mother (Kiyoko Tsuji) witnessed the hit-and-run and is determined to exact revenge, joined by Yoko (Akiko Ono), Kyōichi’s girlfriend.

Nobuo Nakagawa’s Jigoku takes viewers on a dark journey through hell

Shirō is called home to visit his ill mother, Ito (Kimie Tokudaij), while his corrupt father, shady businessman Gōzō (Hiroshi Hayashi), shamelessly has an open affair with Kinuko (Akiko Yamashita). Shirō takes an instant liking to his mother’s nurse, Sachiko Taniguchi (Mitsuya), who looks almost exactly like Yukiko, but her father, painter Ensai Taniguchi (Jun Ōtomo), is being threatened by dirty Det. Hariya (Hiroshi Shingûji), who wants Sachiko for himself or else he will arrest Ensai for a long-ago crime. Sachiko’s appearance frightens Yukiko’s parents, Professor Yajima (Torahiko Nakamura), who is Shirō’s teacher, and his wife (Fumiko Miyata), who are shocked by the doppelgänger. Also hanging around are Dr. Kusama (Tomohiko Ōtani) and journalist Akagawa (Kôichi Miya), who have secrets of their own. As people start dropping like brutally swatted and electrocuted flies, Shirō takes all of the blame even though he does not cause any of the deaths directly. (Even the production studio, Shintoho, didn’t survive, declaring bankruptcy after releasing the film.)

But none of that matters once everyone is in hell, facing a series of horrific tortures that are spectacularly photographed by Mamoru Morita, who enjoys keeping the color red at or near the center of most images, along with occasional touches of blue and green. Inspired by the Ōjōyōshū, the tenth-century Buddhist text about birth, rebirth, and the realms of hell, Nakagawa cowrote the screenplay with Ichirō Miyagawa; Nakagawa made nearly one hundred films in just about every genre before he died in 1984 at the age of seventy-nine, but Jigoku is his crowning achievement. It’s horror of the highest order, immersed in a jaw-dropping madness. It’s also a warning, since everyone is a sinner in one way or another, and retribution awaits us all.

Masaki Kobayashi paints four chilling, ghostly portraits in Kwaidan, including “Hoichi, the Earless”

KWAIDAN (Masaki Kobayashi, 1964)

Sunday, March 10, 3:00

filmforum.org

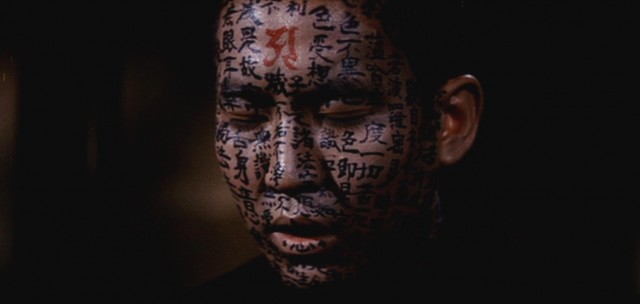

In the mesmerizing Kwaidan, based on folkloric tales by Lafcadio Hearn, aka Koizumi Yakumo, Masaki Kobayashi (The Human Condition, Samurai Rebellion) paints four marvelous ghost stories, each one with a unique look and feel. In “The Black Hair,” a samurai (Rentaro Mikuni) regrets his choice of leaving his true love for societal advancement. Yuki (Keiko Kishi) is a harbinger of doom for a woodcutter (Nakadai) in “The Woman of the Snow.” Hoichi (Katsuo Nakamura) must have his entire body covered in prayer in “Hoichi, the Earless.” And Kannai (Kanemon Nakamura) finds a creepy face staring back at him in “In a Cup of Tea.” The four films subtly, and not so subtly, explore such concepts as greed and envy, love and loss, and the art of storytelling itself. Winner of the Special Jury Prize at Cannes, Kwaidan is one of the greatest ghost story films ever made, a quartet of chilling existential tales that will get under your skin and into your brain. The score was composed by Tōru Takemitsu, who said of the film, “I wanted to create an atmosphere of terror.” He succeeded.

Model Eihi Shiina makes a stunning debut in Takashi Miike’s Audition

AUDITION (ÔDISHON) (Takashi Miike, 1999)

Sunday, March 10, 6:10

filmforum.org

When Audition opened in 1999 at Film Forum, it was New Yorkers’ major introduction to the work of Japanese director Takashi Miike — and some cineastes ran out of the theater faster than they lined up around the block to get in in the first place. The shocking, unconventional psychosexual horror classic, which won the FIPRESCI Prize and the KNF Award at the Rotterdam International Film Festival, will likely have people lining up at Film Forum again. But this is a different (#MeToo, social-media-obsessed) era, so don’t expect many walkouts, although there will be plenty of head-turning and face-covering. There also will be a critical reevaluation of the film’s central concept, a misogynistic male fantasy that evolves into torture/revenge porn.

Yoshikawa Yasuhisa (Jun Kunimura) and Aoyama Shigeharu (Ryo Ishibashi) get more than they bargained for in Audition

Written by Daisuke Tengan based on the novel by Ryu Murakami, Audition begins like a Japanese family melodrama. The gentle-hearted Aoyama Shigeharu (Ryo Ishibashi) watches his wife, Ryoko (Miyuki Matsuda), die in a hospital, leaving him to raise their young son, Shigehiko. Seven years later, the teenage Shigehiko (Tetsu Sawaki) thinks it’s time for his father to find a new wife, as does Aoyama’s best friend, filmmaker Yoshikawa Yasuhisa (Jun Kunimura). Yoshikawa and Aoyama decide to hold fake auditions so the lonely widower can find just the right new romantic partner. He is immediately drawn to the younger, damaged Asami Yamazaki (Eihi Shiina in her stunning film debut), a suicidal former ballerina with a sketchy past filled with questions that worry Yoshikawa. But Aoyama starts dating her anyway, and what starts out sweetly ends up something entirely different as he meets a onetime music executive (Ren Osugi) and an old dance teacher (Renji Ishibashi) who — well, you’ll just have to see that for yourself. The last half hour is so brutal, so grotesque, so disturbing, so violent that you should hang on only at your own risk as it travels “deeper, deeper, deeper” into the psyche, among other things.

There’s something not quite right with Asami Yamazaki (Eihi Shiina) in Takashi Miike’s Audition

Intimately photographed by Hideo Yamamoto and featuring an ominous score by Kōji Endō, Audition has lost none of its power to thrill and chill, right down to the bone. The film has always raised issues of misogyny and male guilt, but, viewed in 2024, those elements come to the fore. The scene in which Yoshikawa and Aoyama interview numerous women contains more than a few cringeworthy stereotypes, and the flashbacks of the abuse suffered by Asami as a child feel more manipulative today. Essentially, Audition is a film that could spring only from a male brain. That said, it is still terrifying twenty-five years later. Miike (Ichii the Killer, The Happiness of the Katakuris), who has directed nearly a hundred films in his three-decade career, from Westerns and yakuza movies to children’s fare and superhero flicks, is best known for the graphic violence in his films, but he also has a wild sense of humor and a knack for making audiences think, “Oh no he won’t,” and then he does. And it’s Audition that cemented that well-earned reputation.

ICHI THE KILLER (Takashi Miike, 2001)

Sunday, March 10, 8:30

filmforum.org

Takashi Miike, who had New York filmgoers rushing to Film Forum to see Audition — and then rushing to get out because of the violent torture scenes — did it again with Ichi the Killer, a faithful adaptation of Hideo Yamamoto’s hit manga. When Boss Anjo goes missing while beating the hell out of a prostitute, his gang, led by Kakihara (Tadanobu Asano), a multipierced blond sadomasochist, tries to find him by threatening and torturing members of other gangs. As the violence continues to grow — including faces torn and sliced off, numerous decapitations, innards splattered on walls and ceilings, body parts cut off, and self-mutilation — the killer turns out to be a young man named Ichi (Nao Omori), whose memory of a long-ago brutal rape turns him into a costumed avenger, crying like a baby as he leaves bloody mess after bloody mess on his mission to rid the world of bullies. This psychosexual S&M gorefest, which is certainly not for the squeamish, comes courtesy of the endlessly imaginative Miike, who trained with master filmmaker Shohei Imamura and seems to love really sharp objects. The excellent — and brave — cast also includes directors Sabu and Shinya Tsukamoto, composer Sakichi Satô, and Hong Kong starlet Alien Sun.

Washizu (Toshirô Mifune) and his wife, Asaji (Isuzu Yamada), reimagine Shakespeare tragedy in Kursosawa classic

THRONE OF BLOOD, AKA MACBETH (KUMONOSU JÔ) (Akira Kurosawa, 1957)

Tuesday, March 12, 12:20

filmforum.org

Akira Kurosawa’s marvelous reimagining of Macbeth is an intense psychological thriller that follows one man’s descent into madness. Following a stunning military victory led by Washizu (Toshirô Mifune) and Miki (Minoru Chiaki), the two men are rewarded with lofty new positions. As Washizu’s wife, Asaji (Isuzu Yamada, with spectacular eyebrows), fills her husband’s head with crazy paranoia, Washizu is haunted by predictions made by a ghostly evil spirit in the Cobweb Forest, leading to one of the all-time classic finales. Featuring exterior scenes bathed in mysterious fog, interior long shots of Washizu and Asaji in a large, sparse room carefully considering their next bold move, and composer Masaru Sato’s shrieking Japanese flutes, Throne of Blood is a chilling drama of corruptive power and blind ambition, one of the greatest adaptations of Shakespeare ever put on film.

Genjurō (Masayuki Mori) makes his pottery as son Genichi (Ikio Sawamura) and wife Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka) look on in UGETSU

UGETSU (UGETSU MONOGATARI) (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1953)

Tuesday, March 12, 2:40

filmforum.org

Ugetsu is one of the most important and influential — and greatest — works to ever come from Japan. Winner of the Silver Lion for Best Director at the 1953 Venice Film Festival, Kenji Mizoguchi’s seventy-eighth film is a dazzling masterpiece steeped in Japanese storytelling tradition, especially ghost lore. Based on two tales by Ueda Akinari and Guy de Maupassant’s “How He Got the Legion of Honor,” Ugetsu unfolds like a scroll painting beginning with the credits, which run over artworks of nature scenes while Fumio Hayasaka’s urgent score starts setting the mood, and continues into the first three shots, pans of the vast countryside leading to Genjurō (Masayuki Mori) loading his cart to sell his pottery in nearby Nagahama, helped by his wife, Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka), clutching their small child, Genichi (Ikio Sawamura). Miyagi’s assistant, Tōbei (Sakae Ozawa), insists on coming along, despite the protestations of his nagging wife, Ohama (Mitsuko Mito), as he is determined to become a samurai even though he is more of a hapless fool.

“I need to sell all this before the fighting starts,” Genjurō tells Miyagi, referring to a civil war that is making its way through the land. Tōbei adds, “I swear by the god of war: I’m tired of being poor.” After unexpected success with his wares, Genjurō furiously makes more pottery to sell at another market even as the soldiers are approaching and the rest of the villagers run for their lives. At the second market, an elegant woman, Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyō), and her nurse, Ukon (Kikue Mōri), ask him to bring a large amount of his merchandise to their mansion. Once he gets there, Lady Wakasa seduces him, and soon Genjurō, Miyagi, Genichi, Tōbei, and Ohama are facing very different fates.

Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyō) admires Genjurō (Masayuki Mori) in Kenji Mizoguchi postwar masterpiece

Written by longtime Mizoguchi collaborator Yoshitaka Yoda and Matsutaro Kawaguchi, Ugetsu might be set in the sixteenth century, but it is also very much about the aftereffects of World War II. “The war drove us mad with ambition,” Tōbei says at one point. Photographed in lush, shadowy black-and-white by Kazuo Miyagawa (Rashomon, Floating Weeds, Yojimbo), the film features several gorgeous set pieces, including one that takes place on a foggy lake and another in a hot spring, heightening the ominous atmosphere that pervades throughout. Ugetsu ends much like it began, emphasizing that it is but one postwar allegory among many. Kyō (Gate of Hell, The Face of Another) is magical as the temptress Lady Wakasa, while Mori (The Bad Sleep Well, When a Woman Ascends the Stairs) excels as the everyman who follows his dreams no matter the cost; the two previously played husband and wife in Rashomon Mizoguchi, who made such other unforgettable classics as The 47 Ronin, The Life of Oharu, Sansho the Bailiff, and Street of Shame, passed away in 1956 at the age of fifty-eight, having left behind a stunning legacy, of which Ugetsu might be the best, and now looking better than ever.