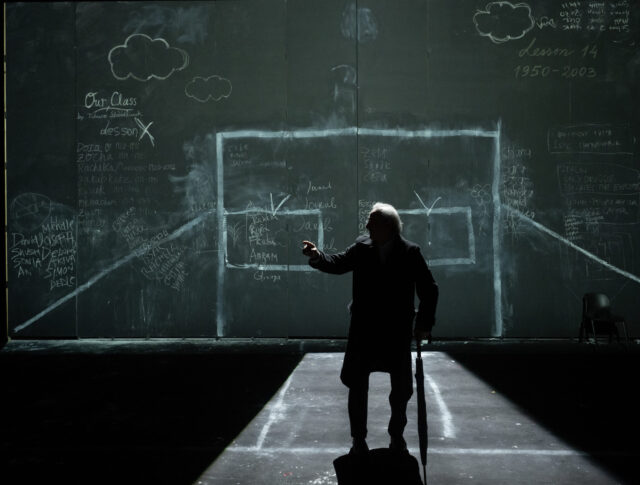

Our Class recounts a 1941 Polish pogrom and its aftermath (photo by Pavel Antonov)

UNDER THE RADAR: OUR CLASS

BAM Fisher, Fishman Space

321 Ashland Pl.

January 12 – February 11, $68-$139

www.bam.org

ourclassplay.com

“I’m going to have a copy of this play put in the cornerstone and the people a thousand years from now’ll know a few simple facts about us — more than the Treaty of Versailles and the Lindbergh flight. See what I mean?” the stage manager says in Thornton Wilder’s 1938 Pulitzer Prize–winning drama Our Town. “So — people a thousand years from now — this is the way we were in the provinces north of New York at the beginning of the twentieth century. — This is the way we were: in our growing up and in our marrying and in our living and in our dying.”

In Igor Golyak‘s potent new revival of Tadeusz Słobodzianek’s 2008 play, Our Class, at BAM Fisher’s Fishman Space through February 11 as part of the Under the Radar festival, the first and second acts start with the cast sitting in a semicircle, holding and reading from scripts, as if copies of the play have been recently unearthed from a cornerstone, revealing a terrifying story that is not as widely known as it should be, and all too relevant to what is happening in the world today.

Inspired by actual events that occurred in the small village of Jedwabne, Poland, Our Class follows a group of ten Polish students, five Jewish, five Catholic, all born in 1919–20, from childhood to young adulthood to old age, although several don’t make it through a 1941 pogrom.

The audience is shown immediately when each character dies; their birth and death dates are written in chalk on a large, multipurpose blackboard. I preferred not to look too closely, instead learning their fate over the course of the narrative, but Golyak and Słobodzianek clearly want you to know who is going to live and who is going to die in their early twenties, in awful ways.

Richard Topol plays Abram Piekarz, the only Polish Jew who got out in time (photo by Pavel Antonov)

Richard Topol portrays Abram Piekarz, who serves as a kind of stage manager. Topol has played similar roles in such important plays about antisemitism as Indecent and Prayer for the French Republic; here he introduces each scene, which are called “lessons,” shuffling props, directly addressing the audience, blowing harp, appearing all over the theater (including in the aisles and on top of the blackboard), and remaining in touch with his fellow classmates after he moves to America and studies to become a rabbi.

At the start of the show, the characters share their hopes and dreams: Dora (Gus Birney) wants to be a movie star, Rysiek (José Espinosa) a pilot, Zocha (Tess Goldwyn) a seamstress, Zygmunt (Elan Zafir) a soldier, Rachelka (Alexandra Silber) a doctor, Jakub Katz (Stephen Ochsner) a teacher. Very few get to achieve their goals.

The first crack in the friendship between the Jews and the Christians occurs in the wake of the death in 1935 of Marshal Józef Piłsudski, who had encouraged minority cultures in the nation. While Jakub is honoring the marshal’s accomplishments, Heniek (Will Manning) mockingly declares, “The marshal’s a prick with a circumcised dick. / His power he loved to abuse. / He married three times and committed his crimes / And sold all us Poles to the Jews!”

Later, the Christian students hold a prayer service in school, which upsets Menachem (Andrey Burkovskiy), Jakub, and Rachelka, who chastises Władek (Ilia Volok) for throwing rocks at Jakub’s sister.

And then, during a party for the opening of a local cinema — made possible by the Soviet occupation of Poland — Rysiek shouts, “Death to the Commie-Jew Conspiracy. Long live Poland!” He leaves, but when a few of the Christians insist on dancing with Jews, it becomes increasingly uncomfortable.

It’s not long before blood is spilled and people are being brutally murdered.

“Classmates are like family. Better than family,” Zygmunt proclaims.

What happened was no way to treat family.

During the pandemic, Golyak and Massachusetts-based Arlekin Players Theatre broke out of the pack with innovative, interactive livestreamed productions, followed by The Orchard, a hybrid reimagining of The Cherry Orchard with Jessica Hecht and Mikhail Baryshnikov.

Golyak (chekhovOS /an experimental game/, Witness) directs with a frenetic energy that is intoxicating; your eyes are always searching for the unusual, the unexpected. In Our Class, adapted by Norman Allen from a literal translation by Catherine Grovesnor, you won’t find characters just sitting and talking; there is constant motion and action throughout the space. Text is added to the blackboard. Victims are represented by balloons on which the actors draw faces. Two figures watch from overhead. Ladders are dragged across the set, used for multiple purposes. A soccer ball that previously brought the classmates together on their team is turned into a weapon.

Cameras and monitors are pushed onstage, projecting live recordings on the screen and the blackboard, then rolled back to the wings, where actors wait and watch intently when they’re not in the scene. At times there is too much happening all at once, complicated by anachronistic video usage, although it also firmly reminds us that this could happen again, as evidenced by the current rise of antisemitism around the world, particularly following Hamas’s terrorist attack on Israel on October 7.

At three hours (with one intermission), the play is long, but any shorter and its lessons might be lost, and in any case, Golyak never lets it slow down. (Prayer for the French Republic is also three hours but doesn’t feel like it.)

Ten classmates learn more than they ever bargained for in New York premiere of Tadeusz Słobodzianek play (photo by Pavel Antonov)

The cast and crew, who hail from Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Israel, Germany, and the US, are superb. The set is by Jan Pappelbaum of the Schaubühne, with realistic сostumes by Sasha Ageeva, stark lighting by Adam Silverman, original music by Anna Drubich, immersive sound by Ben Williams, choreography by Or Schraiber, and projections by Eric Dunlap.

Topol (King of the Jews, The Normal Heart) is exceptional as Abram, the only one who got out of Poland before the 1941 pogrom; he imbues Abram — who in many ways is a stand-in for America, which entered WWII only when Pearl Harbor was attacked — with a soft, affectionate tenderness. Both Topol and Abram are genuine mensches.

Birney (The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, The Rose Tattoo) will break your heart over and over again as Dora, Espinosa (Take Me Out, Fuente Ovejuna) will infuriate you as the bigoted Rysiek, Silber (Fiddler on the Roof, Hello Again) will shock and annoy you as Rachelka, Goldwyn, in her off-Broadway debut, will charm you as Zocha, and Volok (Gemini Man, The Gaaga) will utterly confound you as Władek. Burkovskiy (Solar Line, The Flight), Zafir (Arcadia, Everybody), Manning (Breitwisch Farm, Just Tell No One), and Ochsner (The Maxims of Panteley Karmanov, Everything’s Fine) round out the excellent ensemble.

Perhaps the best thing about Our Class is that it doesn’t preach at the audience; it has a message and a point of view but is not teaching us about good and evil.

In Our Town, Emily asks the stage manager, “Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it? — every, every minute?”

“No,” the stage manager replies.

And that’s a shame, because no one should have to go through such horrors again.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can find his personal essay on Our Class here.]