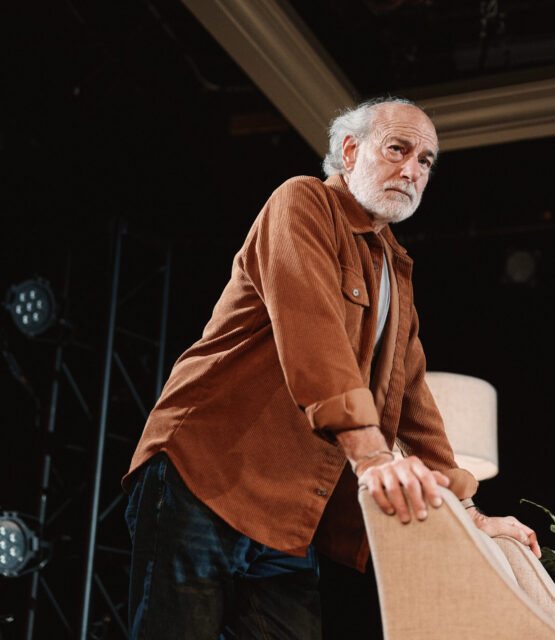

A therapist (Peter Friedman) and his new patient (Sydney Lemmon) fight for survival in Max Wolf Friedlich’s Job (photo by Danielle Perelman)

JOB

Connelly Theater

220 East Fourth St. between Aves. A & B

Wednesday – Monday through March 3, $32-$127

jobtheplay.com

connellytheater.org

Last fall, Max Wolf Friedlich’s Job became one of the hottest tickets in town, spurred not only by the quality of the production but by a TikTok rave from moschinodorito, aka actor Connor Boyd.

The show, with the same cast and crew, is now having an encore run through March 3, moving from SoHo Playhouse to the Connelly Theater on the Lower East Side.

Below is my original review from last October; tickets are likely to go fast, so get your resumes in now. . . .

——————————————————————————————————————-

The title of Max Wolf Friedlich’s intense generational thriller, Job, can be pronounced either with a soft o, meaning the type of work someone does, or with a hard o, referring to the biblical figure. Both characters in the world premiere at SoHo Playhouse will have to display patience and an innate understanding of their employment if they are going to survive this intense tale.

The show takes place in January 2020 in the San Francisco office of a therapist named Loyd (Peter Friedman), a sort of 1960s throwback who has to determine whether Jane (Sydney Lemmon) can return to her position in the tech world after having suffered a terrible psychological meltdown that went viral. As the play opens, Jane is holding a gun on Loyd.

“Thanks for squeezing me in,” she says plaintively, sitting down. “My pleasure. In general, do Wednesdays at this time work?” he asks, trying to ignore that his life appears to be in grave danger. For the next eighty minutes, Jane and Loyd play a kind of verbal cat-and-mouse game as facts slowly emerge explaining how it came to this.

Jane insists she is not a gun person but that her mental state is on the edge. She tells him, “I can’t imagine how scary that was for you — it was scary for me too — but I promise, I swear like . . . I will do whatever you need me to do just . . . I can’t be outside right now, I — I haven’t slept in a couple days, I haven’t — I can’t be outside, I just need to get back to work.”

Jane (Sydney Lemmon) believes she desperately needs to get back to work in Job (photo by Danielle Perelman)

Meanwhile, Loyd, responding to the shame Jane says she feels for having the gun, explains, “I’m not an especially spiritual person — at least not in the traditional sense — but I will contend that the people who wrote the Bible down were some very very clever people. We’re told that Adam and Eve eat the sort of magical wisdom apple, right? They eat the apple, realize they’re naked, and then . . . they feel shame. So shame is the very first feeling mentioned in the Bible — wisdom and shame are connected.”

Those two elements also arise in the Book of Job. “But where can wisdom be found? And where is the place of understanding? Man does not know its value, nor is it found in the land of the living,“ Job says to his friends. Shortly after, God says to Job, “Your enemies will be clothed in shame, and the tents of the wicked will be no more.”

As the two protagonists continue to battle it out, an underlying theme begins to emerge, one of the young fighting against the old. Jane is in her twenties, working in the tech profession in a role that didn’t exist a mere ten years before, while Loyd, in his sixties, is a laid-back Berkeley grad with outdated sensibilities.

“It’s the field that’s the problem,” Jane tells him. “Because people with your job come into work wanting to connect trauma A to trauma D, so they always do — it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy or whatever.” When Jane explains how a creepy guy on a train both hit on her and insulted her at the same time, Loyd defends it as “a misguided attempt at being friendly — generational miscommunication.” She also asks Loyd, “Like why are you so terrified of progress?”

Loyd delves into Jane’s upbringing, looking for clues regarding her meltdown, but keeps coming up empty. “It was a perfectly nice granola middle class existence — nothing to cry about,” she insists. Jane, however, often turns the tables on Loyd, asking him personal questions that he does answer, perhaps out of fear knowing that there’s still that gun in her bag. But once he’s said enough, a major twist leads to an intense finale.

Loyd (Peter Friedman) is the arbiter of Jane’s fate in world premiere at SoHo Playhouse (photo by Danielle Perelman)

No matter how you pronounce it, Job is a nail-biter about patience, wisdom, and, primarily, responsibility, about people being accountable for their actions and living up to their obligations. Both Jane, who works in “user care,” and Loyd have jobs in which they help people, though in different ways, through a kind of protection.

In his off-Broadway debut, director Michael Herwitz keeps the drama at high-boil, making good use of Scott Penner’s basic set, a few chairs facing each other atop a rectangular, carpeted platform, with two small tables, an ottoman, and a lamp. Mextly Couzin’s lighting features several eerie blackouts, accompanied by Jessie Char and Maxwell Neely-Cohen’s effective sound. The costumes by Michelle Li consist of casual pants and an unbuttoned shirt for Loyd and green pants and a belly-revealing striped shirt for Jane.

Ever-reliable Tony nominee Friedman (The Nether, Ragtime) is phenomenal as an easygoing therapist who suddenly find his life on the line, while Lemmon (Tár, Helstrom) — the daughter of Chris Lemmon and granddaughter of Jack Lemmon — is exceptional in her off-Broadway debut, stretching her long body, clasping her hands, and holding tight to her gun as she slowly reveals some hidden truths. (Friedman played series regular Frank on Succession, while Lemmon appeared in three episodes as Jennifer, who’s starring in Willa’s play.)

The twist is a biggie and will turn some people off, as will the open-ended finale. But everything up to those points is taut and nerve-racking. It’s not going to hurt any of the participants to have this Job on their resume.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]