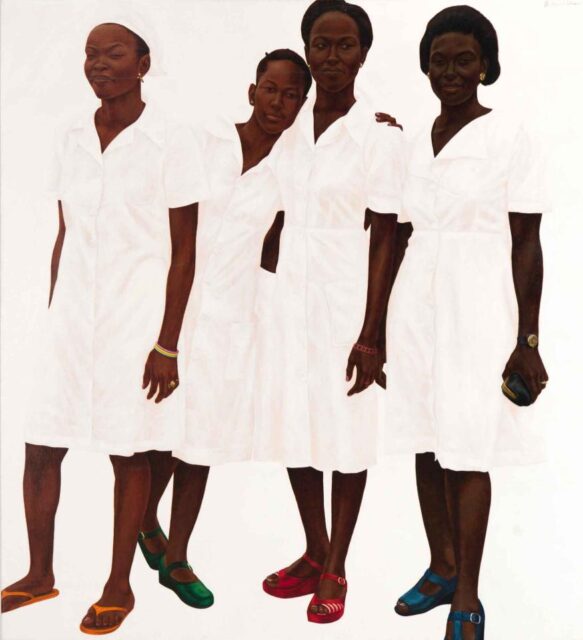

Barkley L. Hendricks, Lagos Ladies (Gbemi, Bisi, Niki, Christy), oil, acrylic, and Magna on canvas, 1978 (private collection / © Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)

BARKLEY L. HENDRICKS: PORTRAITS AT THE FRICK

Frick Madison

945 Madison Avenue at Seventy-Fifth St.

Thursday – Sunday through January 7, $12-$22, 10:00 am – 6:00 pm

www.frick.org

My favorite specific spot in New York City museums right now is near the center of the larger of the rooms at Frick Madison containing the stunning exhibition “Barkley L. Hendricks: Portraits at the Frick.” Facing south, about ten or twelve steps from an inner doorway, you can see a pair of James McNeill Whistler full-size portraits in the small space, Harmony in Pink and Grey: Portrait of Lady Meux, from 1881–82, and Symphony in Flesh Colour and Pink: Portrait of Mrs. Frances Leyland, from 1871–74.

But on either side of the entrance to the Whistler room are two works by Hendricks, who was born in 1945 in Philadelphia and died in Connecticut in 2017 at the age of seventy-two. (Whistler was born in 1834 in Massachusetts and died in London in 1903 at the age of sixty-nine.) To the right is Ma Petite Kumquat, a 1983 portrait of Hendricks’s wife, Susan, while on the left is Miss T, a 1969 portrait of Hendricks’s girlfriend at the time, Robin Taylor. (Lady Meux was a working-class woman who married a brewery fortune heir and was never accepted by his family; Mrs. Leyland was a close friend of Whistler’s who was married to a Liverpool shipping magnate.)

The differences among these four large-scale vertical portraits are striking; grouping them together this way at the prestigious Frick, home to myriad masterpieces from the Renaissance to the early twentieth century, is an ingenious decision by curator Aimee Ng and consulting curator Antwaun Sargent.

“The Frick Collection was one of [Hendricks’s] favorite museums, to which he returned again and again to visit paintings by Rembrandt, Van Dyck, Bronzino, and many others. All three floors of Frick Madison are the context for this special exhibition; though Hendricks’s paintings are installed only here, on the fourth floor,” Ng said in a statement.

Sargent added, “When Aimee and I first began speaking about the Frick and its place in today’s world, I suggested an exhibition on Barkley L. Hendricks — obviously because of his interest in historic art as he developed his own style of portraiture of Black subjects, but also because the quality, dignity, and visual impact of his paintings are what I would think Henry Clay Frick might be drawn to if he were collecting now, thinking of future visitors to the museum in another hundred years. . . . Presenting Hendricks’s art at a storied institution like the Frick pays due tribute to the historic significance of Barkley L. Hendricks, and it also honors the evolving role of the Frick in modern American culture.”

Mrs. Leyland and Lady Meux each wear long, light-colored elegant gowns that spread onto the floor: The former stands with her back to us, hands clasped, the flower designs on her dress matching the flowers in front of her as she looks wistfully off to the side; the latter, in a hat with a flower on it, is looking right at the viewer as her body faces away, one hand grasping her dress, making sure we understand her station.

About one hundred years later, Taylor, in all-black except for a metallic chain around her waist, is looking wistfully off to the side, her body facing us, hands behind her back, her afro a modern contrast to Mrs. Leyland’s up-do. Meanwhile, Susan is also facing us, but her eyes are closed; she is wearing a black outfit with a red flower on it, a bow tie, a green curtain pull across her shoulder (evoking the background of Hans Holbein’s Frick masterwork, his portrait of Sir Thomas More), woolly leg warmers, and red and green bows on her open-toed shoes, her nails painted, a leopard skin pillbox muff in her left hand.

The two pairs of paintings encapsulate hundreds of years of art history dominated by race, gender, and class, as Hendricks uses his early influences to capture a more honest present. “I wasn’t a part of any ‘school,’” he said in 2017. “The association I had with artists in Philadelphia didn’t inspire me in any direction other than my own. I spent my time looking to the Old Masters.” He also insisted, “It had to be done Barkley Hendricks style — no copies.”

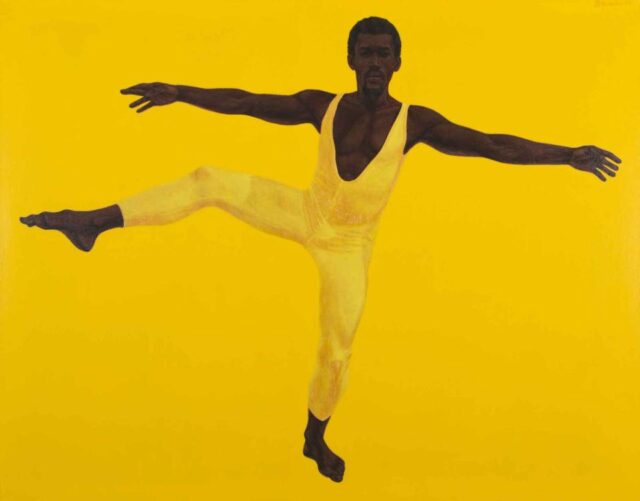

Barkley L. Hendricks, Woody, oil and acrylic on canvas, 1973 (Baz Family Collection / © Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)

The exhibition features five canvases in which the Black subjects — October’s Gone . . . Goodnight, Steve, Lagos Ladies (Gbemi, Bisi, Niki, Christy), Slick, Omarr — are wearing white against a white background so their skin and hair color seem to be floating in space; in Woody, Jamaican American dancer Woodruff (Woody) Wilson has his two arms and one leg stretched out, in yellow leotards against a yellow background. In Lawdy Mama, Hendricks sets his relative Kathy William against a gold-leaf background with a rounded top, echoing Italian Renaissance gold-leaf works, of which many are currently on view at the Frick.

In conjunction with the exhibit, Nasher Museum of Art director Trevor Schoonmaker has compiled a special 1960s/1970s playlist, with a specific song for each painting as well as intro and outro tunes; for example, Rotary Connection’s “I Am the Black Gold of the Sun” for Lawdy Mama, Don Cherry’s “Birdboy” for Woody, Gil Scott-Heron’s “I Think I’ll Call It Morning” for Miss T, Roy Ayers’s “Everybody Loves the Sunshine” for October’s Gone . . . Goodnight, and Bob Marley’s “Natural Mystic” for Omarr.

The Frick has been moving into the twenty-first century for several years now, beginning with “Elective Affinities: Edmund de Waal at the Frick Collection” in 2019, in which the author and ceramicist created site-specific vitrines of objects made of porcelain, steel, gold, alabaster, and aluminum and placed them throughout the museum, and continued during the pandemic at Frick Madison with “Olafur Eliasson and Claude Monet,” “Propagazioni: Giuseppe Penone at Sèvres,” “Living Histories: Queer Views and Old Masters,” and the current “Nicolas Party and Rosalba Carriera.” Here’s hoping the trend continues once the Frick moves back to its renovated home on Fifth Ave. later this year.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]