CLOSE-UP: FILMS ON FILM

Metrograph

7 Ludlow St. between Canal & Hester Sts.

Through September 24

212-660-0312

metrograph.com/film

Americans are so obsessed with movies that we are even obsessed with movies about movies. Metrograph tracks that obsession in the wide-ranging series “Close-up: Films on Film.” Running through September 24, the celebration includes such classics as Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly’s Singin’ in the Rain and Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, such foreign favorites as Federico Fellini’s 8½ and Giuseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso, and such lesser-known gems as Peter Strickland’s Berberian Sound Studio and Tsai Ming-liang’s The River in addition to works by Robert Altman, Olivier Assayas, Spike Jonze, Tim Burton, Joanna Hogg, and Pedro Almodóvar. Below is a close-up look at seven movies about movies you can catch at Metrograph this month.

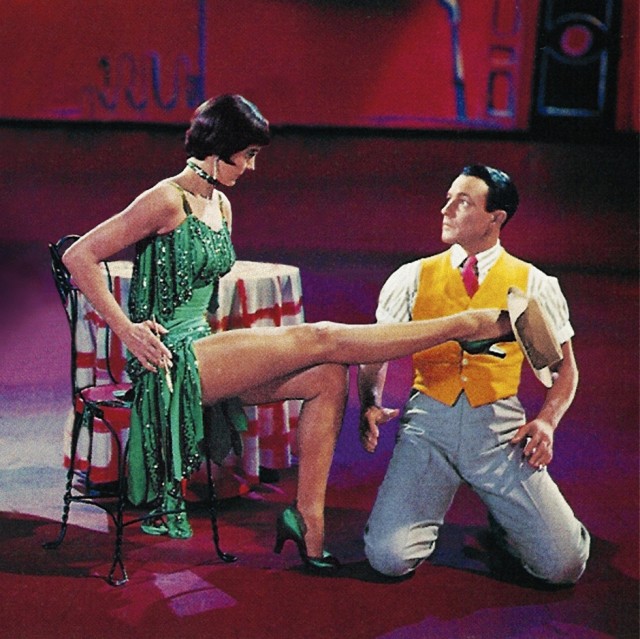

SINGIN’ IN THE RAIN (Stanley Donen & Gene Kelly, 1952)

Tuesday, September 5, 6:00

Thursday, September 7, 4:00

metrograph.com

The MGM musical Singin’ in the Rain is one of the all-time-great movies about movies, in this case focusing on the treacherous transition from silent films to talkies. It’s the mid-1920s, and the darlings of the silver screen are handsome Don Lockwood (Gene Kelly) and blonde bombshell Lina Lamont (Jean Hagen). They’re supposedly just as hot offscreen as on, as Don explains to radio gossip host Dora Bailey (Madge Blake, later best known as Aunt Harriet on the Batman TV series) at their latest Hollywood premiere, but in actuality the debonair Don can’t stand the none-too-bright yet still conniving Lina. After accidentally bumping into Kathy Selden (Debbie Reynolds), an independent-thinking young woman who claims to not even like the movies, Don is soon trying to chase her down, determined to get to know her better. Meanwhile, studio head R. F. Simpson (Millard Mitchell) decides he has to capitalize on the surprise success of the first talking picture, The Jazz Singer, by turning the latest Lockwood-Lamont movie, The Dueling Cavalier, into a talkie, with initially disastrous results, threatening to bring everything and everyone crashing down.

Written by the legendary team of Betty Comden and Adolph Green and directed by Kelly and Stanley Donen (On the Town, Charade), Singin’ in the Rain is an endlessly thrilling and entertaining film, featuring gorgeous Technicolor set pieces photographed by Harold Rosson (the Broadway Melody ballet with Cyd Charisse is particularly spectacular), terrific tunes adapted from previous productions (“Fit as a Fiddle [And Ready for Love,]” “Moses Supposes,” “Good Morning”), and delightful performances by Kelly, whose solo foray through the title song is deservedly iconic; Donald O’Connor as Don’s longtime best friend, Cosmo Brown, who dazzles with a comic Fred Astaire-like turn in “Make ’em Laugh”; and Hagen channeling Judy Holliday from Born Yesterday. (Hagen served as Holliday’s understudy when Born Yesterday hit Broadway in 1947.)

While all the elements come together beautifully (although things do get a little too mean-spirited in the end), this is Kelly’s film all the way, his smile and charm dominating the screen as only a genuine movie star can, so to see him playing a movie star merely doubles the fun. (It’s hard to imagine that Howard Keel was supposedly the first choice to play the role.) Curiously, Singin’ in the Rain was nominated for only two Oscars, with Hagen getting a nod for Best Supporting Actress and Lennie Hayton for Best Musical Score.

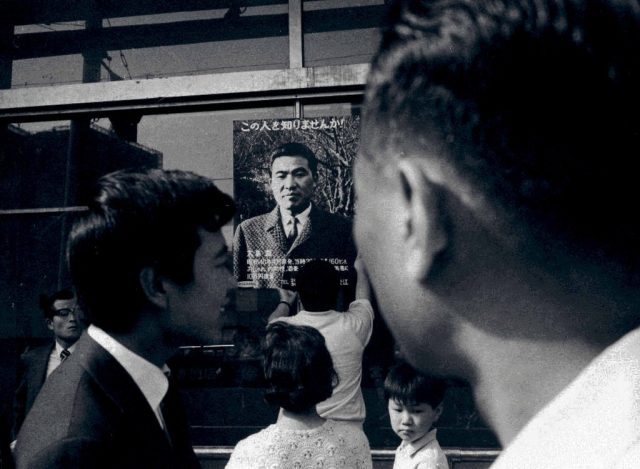

Shôhei Imamura questions the concept of the documentary in A Man Vanishes

A MAN VANISHES (NINGEN JŌHATSU) (Shôhei Imamura, 1967)

Friday, September 8, 2:10

Sunday, September 10, 6:50

metrograph.com

Japanese filmmaker Shôhei Imamura blurs the lines between reality and fiction in his cinéma vérité masterpiece, A Man Vanishes. The 1967 black-and-white documentary delves into one of Japan’s annual multitude of missing persons cases, this time investigating the mysterious disappearance of Tadashi Ôshima, a plastics wholesaler who vanished during a business trip. Imamura sends out actor Shigeru Tsuyuguchi (The Insect Woman, Intentions of Murder) to conduct interviews with Ôshima’s fiancée, Yoshie Hayakawa, who develops an interest in her inquisitor; Yoshie’s sister, Sayo, who quickly finds herself on the defensive; business associates who talk about Ôshima’s drinking, womanizing, and embezzling from the company; and several people who remember seeing Sayo together with Ôshima, something she adamantly denies despite the building evidence.

Throughout the 130-minute work, the film references itself as being a film, culminating in Imamura’s pulling the rug out from under viewers and calling everything they’ve seen into question in an unforgettable moment that breaks down the fourth wall and explodes the very nature of truth and cinematic storytelling itself. It also explores individual identity and just how much one really knows those closest to them. Originally supposed to be the first of a twenty-four-part series exploring two dozen missing-persons cases, A Man Vanishes ended up being such a challenging undertaking that it was the only one Imamura made, but what a film it is; it would be more than a decade before he returned to fiction, with 1979’s Vengeance Is Mine, which led the way to a spectacular final two decades that also included The Ballad of Narayama, Eijanaika, Black Rain, The Eel, Dr. Akagi, and Warm Water Under a Red Bridge.

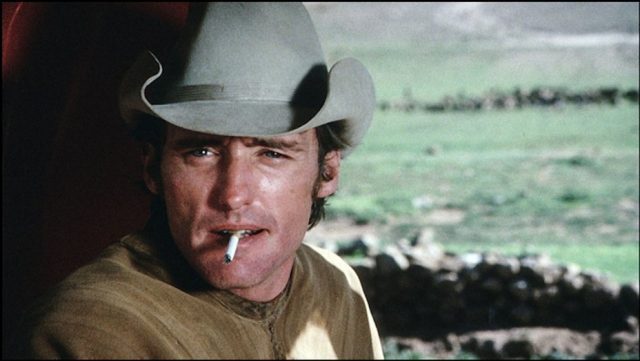

Dennis Hopper found himself in Hollywood exile after making The Last Movie

THE LAST MOVIE (Dennis Hopper, 1971)

Saturday, September 9, 10:45

metrograph.com/film

arbelosfilms.com

Flying high off his international success with Easy Rider in 1969, cowriter, director, and star Dennis Hopper was given carte blanche by Universal for his next film, 1971’s The Last Movie, a controversial picture that, despite winning the Critics Prize at the Venice Film Festival, led to Hopper’s unofficial exile from Hollywood for nearly a decade. The Last Movie was recently released in a gorgeous 4K digital restoration made by Il Cinema Ritrovata from the original 35mm camera negative, returning to Metrograph on September 9. As documented in Nick Ebeling’s 2017 Along for the Ride and elsewhere, The Last Movie was a longtime labor of love for Hopper and his cowriter, Stewart Stern (who had penned Rebel without a Cause, in which Hopper played a key role), but it ended up being a critical and financial flop. Over the years, there have been occasional rare screenings as the film’s legend grew, and the restoration proves that the mythos was fully justified.

Hopper stars as Kansas, a movie wrangler working on a Western about Pat Garrett (Rod Cameron) and Billy the Kid (Dean Stockwell) in Chinchero, Peru, directed by one of the toughest auteurs of them all, the great, cigar-chomping Samuel Fuller (Pickup on South Street, Shock Corridor). Kansas is with former prostitute Maria (Stella Garcia), but he is instantly attracted to the fur-wearing Mrs. Anderson (Julie Adams), the wife of a wealthy factory owner (Roy Engel). Kansas’s best friend, Neville Robey (Don Gordon), wants Mr. Anderson to invest in his gold mine while both Anderson and Maria become jealous of Kansas’s romantic interest in Mrs. Anderson. In addition, following the accidental death of a stunt man during a dangerous scene, the local community of Chinchero blames Kansas and begins making their own movie directed by the vengeful Tomas Mercado (Daniel Ades), using real violence and fake equipment, creating a kind of passion play with Kansas at the center, much to the chagrin of the concerned priest (Tomas Milian), who was never in favor of Hollywood bringing its decadence to his town. It all leads to a stunning, unforgettable finale that questions much of what has come before.

Hopper, who was also a photographer and painter, said about the film, “The Last Movie is something that I made in Peru. I won the Venice Film Festival with it, and Universal Pictures wouldn’t distribute it. You should think about [Jean-Luc] Godard a little when you watch it. I made it because I’d read him say that movies should have a beginning, a middle, and an end — but not necessarily in that order. I was trying to use film like an Abstract Expressionist would use paint as paint. I’m constantly reminding you that we’re making a movie — I’m constantly making references to the fact that maybe you’re just being silly sitting in an audience, being sucked into a movie and starting to believe it — and then I jar you out of it. It’s not a very pleasant experience for most audiences.” But things have changed significantly over the last half-century, and audiences are now more attuned to watching nonlinear, more unorthodox films that merge fiction and reality and challenge them with purposely confusing plot twists and character development. Some scenes repeat, while others might have been lost — several times a title card identifies that a scene is missing, but it is impossible to know whether that is true or Hopper is playing with the viewer yet again. (The film was edited by David Berlatsky, Antranig Mahakian, and Hopper.) In fact, Tomas and the priest regularly refer to moviemaking as a game. It’s also not always clear when we’re watching the film, the film-within-a-film, or even a different film as Hopper explodes genre tropes to continually defy expectations. At one point the soundtrack features Kris Kristofferson singing “Me and Bobby McGee,” but the camera soon finds Kristofferson himself, guitar in hand, warbling away. Thus, when we later hear a song by John Buck Wilkin, we look for him as well.

Beautifully photographed by László Kovács, The Last Movie turns Kansas into a kind of Jesus figure. Both text and image often reference various stories from the Bible, directly and indirectly, including Jesus being whipped, his relationship with prostitute Mary Magdalene, a celebration around a golden calf, Jesus rising from a cave, and Christ being led to the cross. All seven deadly sins — gluttony, lust, greed, sloth, wrath, envy, and pride — enter the narrative. The color red plays a significant role, as if staining the land with blood, from fake movie blood to the color of Kansas’s truck. Everyone ends up guilty of something, with some paying a higher price than others; as the original 1971 production notes explain: “Every character in the film is an innocent. Only as they are tarnished by their participation in the games do they become agents of their own destruction. The dreams that they succumb to are all encompassed in or produced by the American dream. Their sin, however, is the movies.” Hollywood has done them in, as it will Hopper himself, who filled the cast with such nonconventional, mostly non-Hollywood actors as Henry Jaglom, Toni Basil, Severn Darden, Sylvia Miles, Warren Finnerty, Peter Fonda, Clint Kimbrough, John Phillip Law, Russ Tamblyn, and Michelle Phillips, who was married to Hopper for eight days. The two-time Oscar-nominated Hopper went on to direct such films as Out of the Blue, Colors, and The Hot Spot and appear in such works as Apocalypse Now, Blue Velvet, Hoosiers, True Romance, and Speed before passing away in May 2010 at the age of seventy-four. His legacy is now cemented with the restoration of The Last Movie, a masterpiece that finally got the due it, and Hopper, deserved.

Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni) is in a bit of a personal and professional crisis in Fellini masterpiece 8½

8½ (Federico Fellini, 1963)

Friday, September 15, 3:15

Sunday, September 17, 2:00

metrograph.com

“Your eminence, I am not happy,” Guido (Marcello Mastroianni) tells the cardinal (Tito Masini) halfway through Federico Fellini’s self-reflexive masterpiece 8½. “Why should you be happy?” the cardinal responds. “That is not your task in life. Who said we were put on this earth to be happy?” Well, film makes people happy, and it’s because of works such as 8½. Fellini’s Oscar-winning eighth-and-a-half movie is a sensational self-examination of film and fame, a hysterically funny, surreal story of a famous Italian auteur who finds his life and career in need of a major overhaul. Mastroianni is magnificent as Guido Anselmi, a man in a personal and professional crisis who has gone to a healing spa for some much-needed relaxation, but he doesn’t get any as he is continually harassed by producers, screenwriters, would-be actresses, and various other oddball hangers-on. He also has to deal both with his mistress, Carla (Sandra Milo), who is quite a handful, as well as his wife, Luisa (Anouk Aimée), who is losing patience with his lies.

Trapped in a strange world of his own creation, Guido has dreams where he flies over claustrophobic traffic and makes out with his dead mother, and his next film involves a spaceship; it doesn’t take a psychiatrist to figure out the many inner demons that are haunting him. Marvelously shot by Gianni Di Venanzo in black-and-white, scored with a vast sense of humor by Nino Rota, and featuring some of the most amazing hats ever seen on film — costume designer Piero Gherardi won an Oscar for all the great dresses and chapeaux — 8½ is an endlessly fascinating and wildly entertaining exploration of the creative process and the bizarre world of filmmaking itself.

AFTER LIFE (WANDÂFURU RAIFU) (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 1998)

Saturday, September 16, 12:00

metrograph.com

Hirokazu Kore-eda’s second narrative feature, After Life, is an eminently thoughtful film about two of his recurring themes: death and memory. Every Monday, the deceased arrive at a way station where they have three days to decide on a single memory they can bring with them into heaven. Once chosen, the memory is re-created on film, and the person goes on to the next step of their journey, to be replaced by a new batch of souls. The way station is staffed by guides, including Takashi Mochizuki (Arata), Shiori Satonaka (Erika Oda), and Satoru Kawashima (Susumu Terajima), whose job it is to interview the new arrivals and help them select a memory and then bring it to life on-screen. Some want to take with them an idyllic moment from childhood, others a remembrance of a lost love, but a few are either unable to or refuse to come up with one, which challenges the staff. Twenty-one-year-old Yūsuke Iseya declares, “I have no intention of choosing. None,” while seventy-year-old Ichiro Watanabe (Taketoshi Naito) is having difficulty deciding on the exact moment, reevaluating and reflecting on the life he led. As the week continues, the guides look back on their lives as well, sharing intimate details, one of which leads to an emotional finale.

Kore-eda, who previously examined memory loss in the documentary Without Memory and explored a family’s reaction to death in the brilliant Still Walking, interviewed some five hundred people about what memory they would take with them to heaven, and some of those nonprofessional actors are in the final cut of After Life, blurring the lines between fiction and reality. After Life is also very much about the art of filmmaking itself, as each memory is turned into a short movie created on a set and watched in a screening room. In fact, the film was inspired by Kore-eda’s memories of his grandfather’s battle with what would later be identified as Alzheimer’s disease; the director has also cited Ernst Lubitsch’s 1943 comedy, Heaven Can Wait, as an influence, and the Japanese title, Wandâfuru raifu, means “Wonderful Life,” evoking Frank Capra’s holiday classic. But Kore-eda never gets maudlin about life or death in the film, instead painting a memorable portrait of human existence and those simple moments that make it all worthwhile — and will have viewers contemplating which memory they would take with them when the time comes.

Billy Wilder takes audiences down quite a Hollywood road in Sunset Boulevard.

SUNSET BOULEVARD (Billy Wilder, 1950)

Saturday, September 23, 12:15

metrograph.com

“You’re Norma Desmond. You used to be in silent pictures. You used to be big,” handsome young screenwriter Joe Gillis (William Holden) remarks to an older woman in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard. “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small,” the former star (Gloria Swanson) famously replies. It doesn’t get much bigger than Sunset Boulevard, one of the grandest Hollywood movies ever made about Hollywood. The wickedly entertaining film noir begins in a swimming pool, where Gillis is a floating corpse, seen from below. He then posthumously narrates through flashback precisely what landed him there. On the run from a couple of guys trying to repossess his car, the broke Gillis ends up at a seemingly abandoned mansion, only to find out that it is home to Desmond and her dedicated servant, Max Von Mayerling (Erich von Stroheim). They initially mistake Gillis for the undertaker who is coming to perform a funeral service and burial for Desmond’s pet monkey. (You’ve got to see it to believe it.)

When Desmond discovers that Gillis is in fact a screenwriter, she lures him into working with her on her script for a new version of Salome, in which she is determined to play the lead role. “I didn’t know you were planning a comeback,” Gillis says. “I hate that word,” Desmond responds. “It’s a return, a return to the millions of people who have never forgiven me for deserting the screen.” But just as Desmond was unable to make the transition from silent black-and-white films to color and sound pictures, getting Salome off the ground is not going to be as easy as she thinks. Hollywood can be a rather vicious place, after all.

Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) keeps a close hold on screenwriter Joe Gillis (William Holden) in Sunset Boulevard.

Nominated for eleven Oscars and winner of three — for the sharp writing, the detailed art/set decoration, and Franz Waxman’s score, which goes from jazzy noir to melodrama — Sunset Boulevard wonderfully bites the hand that feeds it, skewering Hollywood while making references to such real stars as Rudolph Valentino, Mabel Normand, John Gilbert, Greta Garbo, Wallace Reid, and Tyrone Power and such films as Gone with the Wind and King Kong. Actual publicity stills and movie posters abound, in Paramount offices and Desmond’s spectacularly designed home, which was once owned by J. Paul Getty and would later be used for Rebel without a Cause. Cecil B. DeMille, who directed Swanson in many silent films, plays himself in the movie, seen on set making Samson and Delilah. Desmond’s fellow bridge players are portrayed by silent stars Buster Keaton, H. B. Warner, and Anna Q. Nilsson.

Meanwhile, before Swanson fired him, von Stroheim directed her in the silent film Queen Kelly, which is the movie Max shows Gillis in Desmond’s screening room. (Swanson herself would go on to make only three more feature films; she passed away in 1983 at the age of eighty-four.) John F. Seitz’s black-and-white cinematography and inventive use of camera placement, from underwater to high above the action, makes the most of Hans Dreier’s sets and Swanson’s fabulous costumes and makeup. Sunset Boulevard is the thirteenth and final collaboration between writer-director Wilder and writer-producer Charles Brackett, who together previously made The Lost Weekend and A Foreign Affair. Wilder and Holden would go on to make Stalag 17, Sabrina, and Fedora together. Finally, of course, Sunset Boulevard concludes with one of the greatest quotes in Hollywood history.

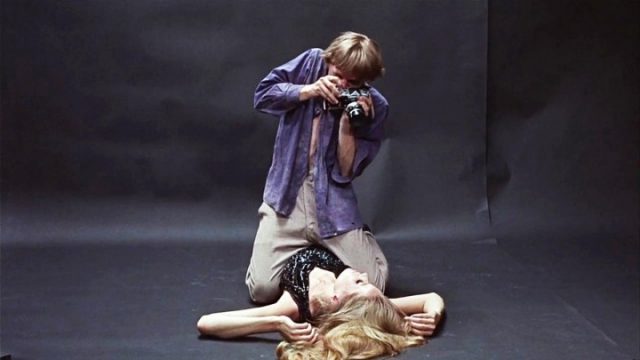

Thomas (David Hemmings) focuses on Veruschka in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up

BLOW-UP (BLOWUP) (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966)

Saturday, September 23, 6:30

Sunday, September 24, 9:30

metrograph.com

Italian auteur Michelangelo Antonioni calls into question everything we see and hear, in photographs, on film, and in real life, in his 1966 counterculture masterpiece, Blow-Up. Antonioni’s first English-language film — part of a three-picture deal with producer Carlo Ponti that would also include the disappointing Zabriskie Point and the quirky existential suspense thriller The Passenger — lets viewers know from the very start that their eyes and ears are going to be tested as the letters of the opening credits frame indecipherable action, frustrating the viewer’s desire to understand what is going on. David Hemmings stars as Thomas, a successful fashion photographer in 1960s Swinging London who is tired of the phoniness and artifice inherent in his profession and instead has ambitions to become a black-and-white documentary photographer, as he and his agent, Ron (Peter Bowles), put together a book focusing on the many ills of society. Of course, he does so while riding around in a Rolls-Royce convertible and in between shooting such models as Veruschka (von Lehndorff), whom he practically makes love to during their session but doesn’t give a hoot about once he puts down the camera. He also gets fed up easily with a quartet of fabulously dressed models (the makeup and clothes come courtesy of costume designer Jocelyn Rickards), telling them to shut their eyes as he leaves, controlling what they see and don’t see, much like a film director. Thomas eventually heads out to lush, green Maryon Park, where he takes pictures of two people, a younger woman (Vanessa Redgrave) cavorting with an older man (Ronan O’Casey), apparently in the midst of a secret tryst. The woman, Jane, rushes over to Thomas and demands he give her the film; he invites her to his studio, where she is willing to do just about anything to get back the negatives. Wondering what was so incriminating about the photographs, Thomas soon makes blow-up after blow-up, examining them closely and ultimately believing that he has captured a murder on film. He also finds out that getting to the truth isn’t going to be easy, especially when he keeps allowing himself to become distracted by his wild lifestyle.

Jane (Vanessa Redgrave) is worried about photos Thomas (David Hemmings) took in Blow-Up

Blow-Up, which was parodied in Mel Brooks’s High Anxiety, reimagined by Brian De Palma as Blow Out, and a direct influence on Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation, was inspired by Julio Cortázar’s short story about a translator, “Las babas del diablo” (“The Devil’s Drool”), and written by Antonioni and regular collaborator Tonino Guerra (L’avventura, L’eclisse, The Red Desert), with English-language dialogue by poet and playwright Edward Bond. Antonioni dances all over the line between fiction and reality: Thomas’s studio belongs to photographer Jon Cowan; many of Thomas’s pictures were taken by photojournalist Don McCullin; Thomas himself is based on London photographer David Bailey; the abstract paintings by Thomas’s neighbor, Bill (John Castle), are by Ian Stephenson; the band in the club scene is the Yardbirds; and the tennis-playing mimes are husband and wife real mimes Claude and Julian Chagrin. Herbie Hancock’s groovy score is primarily heard when Thomas turns on a radio or puts on a record, ambient sound instead of soundtrack music coming from nowhere. Meanwhile, Antonioni challenges the viewer again and again to think twice about what they see and hear. At one point Antonioni follows Thomas’s gaze up into the trees, but when the camera returns to Thomas, he is looking elsewhere. While Thomas is studying the photos he took in the park, trying to uncover what happened as if editing a film, the wind from the park can impossibly be heard. Thomas is often peering through blinds, not sure of what he is seeing. A pair of wannabe models (Jane Birkin and Gillian Hills) tear apart Thomas’s fake photographic background as if breaking the boundaries between the real and the fabricated. When Thomas shows one of the park photographs to Bill’s girlfriend, Patricia (Sarah Miles), she says, “It looks like one of Bill’s paintings.”

And when Yardbirds guitarist Jeff Beck gets frustrated with one of the speakers behind him, he destroys his guitar as bandmates Jimmy Page and singer Keith Relf continue playing “Stroll On” as if nothing is happening. Meanwhile, the crowd stands still like a bunch of zombies, refusing to stroll on or move at all, until Beck throws the broken neck of his guitar, now an object that can no longer emit sounds, into the audience, where it’s up to others to determine its value. The stagnation also relates to a huge propeller Thomas buys from an antiques store, as if he’s desperate to propel his life forward. Does Antonioni really get that literal? It’s hard to tell, but nearly every shot is ripe for interpretation, every directorial decision a careful choice imbued with meaning. When Thomas drives through an antiwar march, two protesters put a sign saying “Go away!” in his backseat, where the propeller will be put later. Blow-Up concludes with one of the most creative finales in the history of cinema. The troupe of mimes seen earlier returns, playing tennis in the park, but without a ball. Just follow the gazes of the mimes and Thomas, and listen closely as well, then watch what he does with his camera. It ingeniously encapsulates everything that has come before, but without a single word being spoken. It’s an absolutely bravura ending to an absolutely bravura film.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]