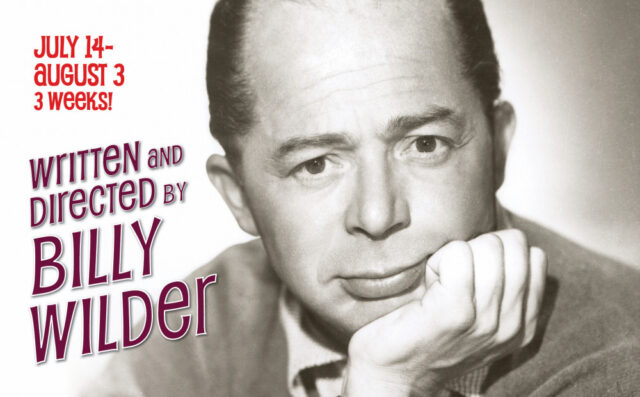

WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY BILLY WILDER

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

July 14 – August 3

filmforum.org

“I have ten commandments,” Billy Wilder once said. “The first nine are, thou shalt not bore. The tenth is, thou shalt have right of final cut.” During his more-than-half-century career, the Austria Hungary—born writer and director wrote and/or directed more than fifty films, making unforgettable works in multiple genres, some of which he essentially created himself. Wilder’s films feature well-drawn characters in familiar and not-so-familiar circumstances in plots that take unexpected twists and turns while subtly exploring society at large — and finding humor in almost any situation.

Wilder made comedies and romances, WWII dramas and biopics, courtroom classics and suspense thrillers. Film Forum is celebrating Wilder’s unique skills in the series “Written and directed by Billy Wilder,” consisting of twenty-nine of his pictures, including four that he wrote but did not direct, in addition to the 1935 French farce Fanfare d’amour, the inspiration for Some Like It Hot.

Wilder knew how to get the most of his actors, as you will see in these films, which show off the talents of Barbara Stanwyck, Fred MacMurray, Edward G. Robinson, Ray Milland, Danielle Darrieux, Claudette Colbert, Don Ameche, John Barrymore, Gary Cooper, Greta Garbo, William Holden, Gloria Swanson, Ginger Rogers, Charles Boyer, Olivia de Havilland, Kirk Douglas, Jean Arthur, James Cagney, Marlene Dietrich, Audrey Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart, Marilyn Monroe, Tony Curtis, Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau, and so many others. Below is a closer look at a handful of the offerings; you really can’t go wrong with any of them, but also high on the must-see list are Stalag 17, Irma la Douce, The Seven Year Itch, The Apartment, Witness for the Prosecution, and One, Two, Three.

“A director must be a policeman, a midwife, a psychoanalyst, a sycophant, and a bastard,” Wilder said. He also pointed out, “If you’re going to tell people the truth, be funny or they’ll kill you.” Wilder died in Beverly Hills in 2002 at the age of ninety-five, having accumulated six Oscars, one honorary Oscar, a Kennedy Center Honor, an AFI Life Achievement Award, a National Medal of Arts, and others, always leaving them laughing.

DOUBLE INDEMNITY (Billy Wilder, 1944)

July 14-17, 31, August 3

filmforum.org

“Written and Directed by Billy Wilder” kicks off with that endlessly romantic noir classic, Double Indemnity. Three years after a brunette Barbara Stanwyck tried to swindle Henry Fonda in Preston Sturges’s The Lady Eve, a blonde Stanwyck is looking for a way out of her loveless marriage when opportunity knocks in the form of acerbic insurance salesman Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray). Stanwyck plays alluring, tough-talking femme fatale Phyllis Dietrichson, who falls for Neff and soon convinces him that they should do away with her husband (Tom Powers). They’re both in it “straight down the line,” as she repeats throughout the film, but insurance fraud investigator Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson) isn’t so sure that Mr. Dietrichson’s death was an accident.

John F. Seitz’s inventive black-and-white cinematography — watch for those Venetian blind shadows — set the standard for the genre. MacMurray, who had to be convinced by Wilder to take the part because he thought he’d be awful in the role, is sensational as Neff, oh-so-cool as he recites his cynical dialogue and lights matches with one hand. He might think he’s tough, but he’s no match for Stanwyck, who rules the roost. Both Stanwyck and MacMurray would go on to successful careers in television in the 1960s, he in My Three Sons, she in The Big Valley. Directed by Wilder from a script he wrote with Raymond Chandler based on a pulp novel by James Cain, with music by Miklós Rózsa — how’s that for a pedigree? — Double Indemnity was nominated for seven Oscars and won none.

Would-be writer Don Birnam (Ray Milland) battles his demons in Billy Wilder classic The Lost Weekend

THE LOST WEEKEND (Billy Wilder, 1945)

July 14-15, 18, 31, August 1

filmforum.org

Ray Milland won an Oscar as Best Actor for his unforgettable portrayal of Don Birnam in Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend, starring as a would-be writer who can see life only through the bottom of a bottle. Having just gotten sober, he is off to spend the weekend with his brother (Phillip Terry), but Don is able to slip away from his girlfriend, Helen (Jane Wyman), and his sibling and hang out mostly with Nat the bartender (Howard Da Silva) and plenty of inner demons. One of the misunderstood claims to fame of Wilder’s classic drama is that it was shot in P. J. Clarke’s on Third Ave.; although the bar in the film was based on Clarke’s, the set was re-created in Hollywood, which doesn’t take anything away from this heartbreaking tale that will not have you running to the nearest watering hole after you see it. The Lost Weekend won three other Academy Awards — Best Screenplay (Wilder and Charles Brackett), Best Director (Wilder), and Best Picture.

Greta Garbo and Melvyn Douglas get involved in a battle of wits and ideologies in Ernst Lubitsch’s classic romantic comedy Ninotchka

NINOTCHKA (Ernst Lubitsch, 2012)

July 16-17

filmforum.org

Greta Garbo laughs — and says she doesn’t want to be alone — in Ernst Lubitsch’s classic pre-Cold War comedy Ninotchka, written by Billy Wilder, Charles Brackett, and Walter Reisch. In her next-to-last film, Garbo is sensational as Nina Ivanovna “Ninotchka” Yakushova, a Russian envoy sent to Paris to clean up a mess left by three comrade stooges, Iranov (Sig Ruman), Buljanov (Felix Bressart), and Kopalsky (Alexander Granach). The hapless trio from the Russian Trade Board had been sent to France to sell jewelry previously owned by the Grand Duchess Swana (Ina Claire) and now in the possession of the government following the 1917 Russian Revolution. But the duchess’s lover, Count Léon d’Algout (Melvyn Douglas), gets wind of the plan and attempts to break up the deal while also introducing the three men to the many decadent pleasures of a free, capitalist society. Then in waltzes the stern, by-the-book Ninotchka, who wants to set the Russian men straight, as well as Léon. “As basic material, you may not be bad,” she tells him atop the Eiffel Tower, “but you are the unfortunate product of a doomed culture.” At first, Ninotchka speaks robotically, spouting the company line, but she loosens up considerably once Léon shows her what communism has been depriving her of, yet it’s difficult for her to turn her back on the cause, leading to numerous hysterical conversations — the razor-sharp script was written by Charles Brackett, Walter Reisch, and Billy Wilder, based on a story by Melchior Lengyel — that serve as both a battle of the sexes and social commentary on the Russian and French ways of life.

“I’ve heard of the arrogant male in capitalistic society. It is having a superior earning power that makes you that way,” Ninotchka tells Léon shortly after meeting him on a Paris street. “A Russian! I love Russians! Comrade, I’ve been fascinated by your Five-Year Plan for the last fifteen years,” Léon responds, to which Ninotchka tersely replies, “Your type will soon be extinct.” Nominated for four Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actress, Best Original Story, and Best Screenplay, Ninotchka is one of the most delightful romantic comedies ever made, filled with little surprises every step of the way (including a serious cameo by Bela Lugosi), serving up a blueprint that has been followed by so many films for nearly three-quarters of a century ever since.

Billy Wilder takes audiences down quite a Hollywood road in Sunset Blvd.

SUNSET BLVD. (Billy Wilder, 1950)

July 17, 22, 23, August 3

filmforum.org

“You’re Norma Desmond. You used to be in silent pictures. You used to be big,” handsome young screenwriter Joe Gillis (William Holden) remarks to an older woman in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Blvd. “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small,” the former star (Gloria Swanson) famously replies. It doesn’t get much bigger than Sunset Boulevard, one of the grandest Hollywood movies ever made about Hollywood. The wickedly entertaining film noir begins in a swimming pool, where Gillis is a floating corpse, seen from below. He then posthumously narrates through flashback precisely what landed him there. On the run from a couple of guys trying to repossess his car, the broke Gillis ends up at a seemingly abandoned mansion, only to find out that it is home to Desmond and her dedicated servant, Max Von Mayerling (Erich von Stroheim). They initially mistake Gillis for the undertaker who is coming to perform a funeral service and burial for Desmond’s pet monkey. (You’ve got to see it to believe it.) When Desmond discovers that Gillis is in fact a screenwriter, she lures him into working with her on her script for a new version of Salome, in which she is determined to play the lead role. “I didn’t know you were planning a comeback,” Gillis says. “I hate that word,” Desmond responds. “It’s a return, a return to the millions of people who have never forgiven me for deserting the screen.” But just as Desmond was unable to make the transition from silent black-and-white films to color and sound pictures, getting Salome off the ground is not going to be as easy as she thinks. Hollywood can be a rather vicious place, after all.

Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) keeps a close hold on screenwriter Joe Gillis (William Holden) in Sunset Blvd.

Nominated for eleven Oscars and winner of three — for the sharp writing, the detailed art/set decoration, and Franz Waxman’s score, which goes from jazzy noir to melodrama — Sunset Blvd. wonderfully bites the hand that feeds it, skewering Hollywood while making references to such real stars as Rudolph Valentino, Mabel Normand, John Gilbert, Greta Garbo, Wallace Reid, and Tyrone Power and such films as Gone with the Wind and King Kong. Actual publicity stills and movie posters abound, in Paramount offices and Desmond’s spectacularly designed home, which was once owned by J. Paul Getty and would later be used for Rebel without a Cause. Cecil B. DeMille, who directed Swanson in many silent films, plays himself in the movie, seen on set making Samson and Delilah. Desmond’s fellow bridge players are portrayed by silent stars Buster Keaton, H. B. Warner, and Anna Q. Nilsson. Meanwhile, before Swanson fired him, von Stroheim directed her in the silent film Queen Kelly, which is the movie Max shows Gillis in Desmond’s screening room. (Swanson herself would go on to make only three more feature films; she passed away in 1983 at the age of eighty-four.) John F. Seitz’s black-and-white cinematography and inventive use of camera placement, from underwater to high above the action, makes the most of Hans Dreier’s sets and Swanson’s fabulous costumes and makeup. Sunset Blvd. is the thirteenth and final collaboration between writer-director Wilder and writer-producer Charles Brackett, who together previously made The Lost Weekend and A Foreign Affair. Wilder and Holden would go on to make Stalag 17, Sabrina, and Fedora together. Finally, of course, Sunset Blvd. concludes with one of the greatest quotes in Hollywood history.

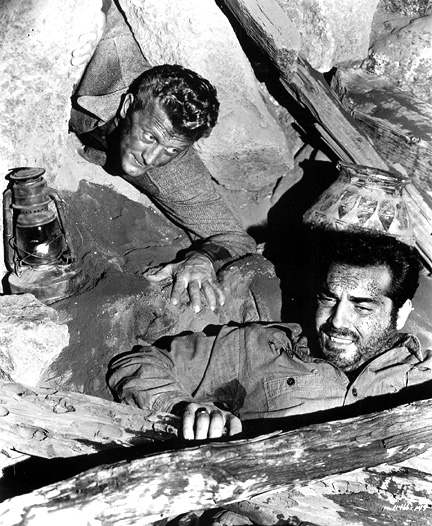

- Kirk Douglas is looking for a way out in Billy Wilder masterpiece Ace in the Hole

ACE IN THE HOLE (Billy Wilder, 1951)

July 20-22

filmforum.org

Sandwiched between such hits as The Lost Weekend, Sunset Blvd., Stalag 17, and Sabrina, Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole might just be his least-known masterpiece. A major flop upon its release in 1951, Ace in the Hole is a cynical look at Americans and their values. Chuck Tatum (a classic Kirk Douglas) is a ruthless reporter who has been fired in every major city in the nation because of his love of the bottle, his success with the ladies, and his penchant for playing hard and loose with the facts. He demands a job at a small-town paper in Albuquerque, hoping to land a story that will restore his luster and put him back in the big time. He finds his patsy in the person of Leo Minosa (Richard Benedict), a low-rent Indian artifacts hunter who gets trapped in a cave-in at the base of the Mountain of the Seven Vultures. Sharpening his fangs, Tatum makes a deal with the sheriff (Ray Teal), choosing to take the long way to rescue Minosa in order to keep the sheriff’s name in the news and the reporter’s name on the front page for a longer amount of time. Meanwhile, Minosa’s wife, Lorraine (Jan Sterling, with fabulously uneven eyebrows), who was ready to leave her husband, sees a way for her to cash in as well. The whole thing turns into a huge media circus; in fact, the studio changed the name of the film to The Big Carnival upon its release, trying for a more upbeat title.