A vulture spies human feet under a wall of plants in bloodred pond in Ebony G. Patterson installation at NYBG (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

. . . things come to thrive . . . in the shedding . . . in the molting . . .

The New York Botanical Garden

2900 Southern Blvd., Bronx

Tuesday – Sunday through October 22, $15 children two to twelve, $31 students and seniors, $35 adults, 10:00 am – 6:00 pm

718-817-8700

www.nybg.org

ebonygpatterson.com

online slide show

“I’m going to give you a show that you’ve not had before,” artist Ebony G. Patterson promised New York Botanical Garden curator Joanna L. Groarke upon preparing for the exhibition “. . . things come to thrive . . . in the shedding . . . in the molting . . . ,” which has just been extended at NYBG through October 22, 2023.

The Jamaica native has done just that, presenting a wide-ranging display that incorporates sculpture, installation, video, collage, and an interactive element, “Things to Be Remembered,” which asks visitors to answer the question “What have you . . . missed . . . felt . . . loved . . . learned . . . witnessed . . . needed . . . heard . . . that you never want to forget?”

“Ebony is the first visual artist to create art at the garden through an immersive residency,” NYBG CEO Jennifer Bernstein said at the preview in May. “This exhibition celebrates the allure of the beautiful while contemplating what lies beneath the enticing surface, the complex tensions of the natural world, and how they reflect the entanglements of race, gender, and colonialism.”

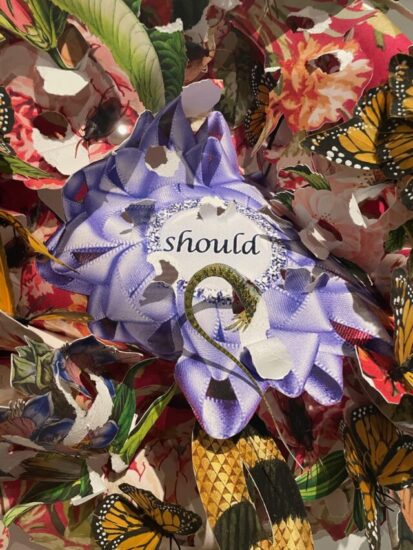

The exhibition features nearly five hundred black foam turkey vultures congregating around the lawn outside the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory and inside the massive greenhouse, as if they’re anticipating a kind of destruction, along with hand-cast glass sculptures of body parts and extinct plants, out in the open and hidden within the confines. You can also hear Patterson’s voice in the soundscape. In the LuEsther T. Mertz Library Building, there are works from Patterson’s “studies from a vocabulary of loss” series, consisting of framed collages with cut-paper flowers and reaching hands, plastic insects, feathered butterflies, and such words as liability, should, wreckage, and goodbye kiss.

The library rotunda is home to . . . fester . . . , a stunning ten-foot horizontal piece laden with woven jacquard fabrics, vertebrae, hand-blown black and white glass plants, and more than a thousand red gloves spreading out onto the floor; yet more vultures hover on ledges above floral patterned wallpaper. Visitors can walk inside the three-channel video installation The Observation: The Bush Cockerel Project, a Fictitious Historical Narrative, in which costumed characters wander through a primordial garden, climate change surrounding the proceedings like, well, vultures.

In putting together the show, Patterson, who lives and works in Kingston and Chicago, was concerned with loss, healing, and regeneration; the intersection of art, horticulture, and science; living and dead plants as ghosts and skeletons; and the materiality of objects, recognizing that both Jamaica and America are postcolonial societies facing problematic issues of income inequality and social injustice.

“What does it mean to think about the word gardens associated with places that are working-class spaces in contrast to a place that is a wealthy neighborhood?” she said. “What does it mean to think about a garden as a site of survival, as a site of social survival? What does it then also mean to think about gardens as it relates to communities that are given particular kinds of care in terms of what is thought of as a space of investment of possibility, and what does it also then mean to think about those gardens that are not given consideration for possibility of care but thrive regardless because that is what happens in nature? Things live on, irrespective of what one puts in nature’s way.”

The centerpiece of the exhibit in the conservatory is an immersive structure topped by a white peacock, as if the rest of the installation bursts from its feathers, ending in a bloodred pond in another room where a wall of plants has seemingly fallen from the sky, a pair of white glass legs sticking out like the feet of the Wicked Witch of the East after Dorothy’s house crushes her in The Wizard of Us. Patterson, who had never before been to NYBG before beginning this project but is a regular at the Hope Botanical Gardens and the adjoining Hope Zoo Kingston in her hometown of Kingston, had only recently seen a rare white peacock there for the first time in her life.

“In seeing this peacock, the peacock was in molting, and it was in a dark enclosure, and the peacock just kind of hovered in the space, ebbing and flowing,” she explained at the preview. “It almost seemed like it was a haunt. And so thinking about what the peacock is — this incredibly beautiful bird with all of its pageantry — and to see it at its ugliest moment remained with me for a year. And so in thinking about that, I couldn’t help but think about the question of what does it mean to witness your ugliness. And so for me, unpacking the garden, in a moment of molting, in a moment of transformation, is about witnessing our collective ugliness, that even in the ugliness, beauty is possible, and in that possibility, we will always find new ways ahead.”

Ebony G. Patterson’s “studies from a vocabulary of loss” are framed collages containing words amid flowers, hands, insects, butterflies, and other elements (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Patterson was also inspired by her residency at Crystal Bridges Museum of Art in Arkansas, where she developed such works as . . . bugs, reptile, fruit, and bush . . . for those who bear/bare witness.

At the preview, I had a chance to speak with Patterson, whose other projects include “Gangstas for Life,” “Disciplez,” and “Invisible Presence: Bling Memories,” a performative piece with embellished coffins.

twi-ny: The first time you ever came to the New York Botanical Garden was in 2019. What were your first impressions walking the grounds?

egp: At the time, there was a show by Roberto Burle Marx [“Brazilian Modern: The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx”], who is a Brazilian artist.

twi-ny: Oh, I loved that show.

egp: Yeah, I mean, the sense of sprawl, and there’s a particular kind of splendor that also exists here, as a place like this does because of its expanse. And then also too because part of its mandate is to create a space of beauty. But then I think the other thing that I was also struck by was the demographics. So I was also also very aware of, oh, who are the people that spend time here? Who are the people that spend a lot of time here? And then I had to say that in thinking about the project, I thought about those people a lot. I thought I would hear stories about women who would come during particular seasons, to see particular flowers, and fussing about the fact that a flower doesn’t grow the same way the next season.

But I think about those people. And also too in terms of how this is such a heightened visual experience. Not everybody goes to museums. For some people the garden is their ultimate visual experience. So what does it mean also to disrupt that for a person so that they also think about this place differently in the same way that one would think about an exhibition very differently when one goes to a museum? Each exhibition presents something different. And I sat with that a lot over the course of thinking through the ideas here.

twi-ny: And you were given pretty much carte blanche to go and do what you needed to do?

egp: Correct. Yes. And the gardens . . . I mean, there were some things that I had proposed that I wanted us to explore that were a little difficult to do, given the time. So there is carte blanche and there is carte blanche, right? But that being said, a lot of this is truly a collaboration because as much as I use plants and I think about using plants in relation to history, all of the knowledge about what it means to grow a plant at a particular time, what it is, how it lives with something else, is not something that I consider at all.

And I come from a place of thinking about things as a painter. So I rely very heavily then on the knowledge of the people who are here, in the same way that I would rely on the knowledge of somebody who works in glass. I love glass materially, but ask me, can I go and forge it, do what’s necessary to make it whole myself? No. Can I sew? It’s the same . . . We all rely on the knowledge base of other people to make things possible, and artists are no different in that history.

twi-ny: Mentioning museums, “Dead Treez” was at the Museum of Arts & Design in 2016. Do you see a direct link between the NYBG show and that one?

egp: Oh, absolutely. When MAD gave me that opportunity in the Tiffany Galleries to make a garden inside their galleries, that was such a huge shift in my own practice. But then also too for MAD, it was a new point of departure for them, for them to be inviting an artist to curate a selection of objects. But then I had the show that was also running concurrently [“. . . while the dew is still on the roses . . .” at Pérez Art Museum Miami], and I was like, “How do I make these two things speak to each other?”

So I think for me, the Museum of Arts & Design project that I did in those Tiffany cases is essentially the seed that’s continued to grow over these years. It’s the very thing that ended up also growing the Pérez show, which was centered on this notion of thinking about a night garden. And then what does it also then mean to pull that all out into the living space? But also, too, the garden isn’t an art institution, but then at the same time, doing this at an art institution just would not be possible, it just wouldn’t.

[For a more personal look at the arts in New York City, follow Mark Rifkin on Substack here.]