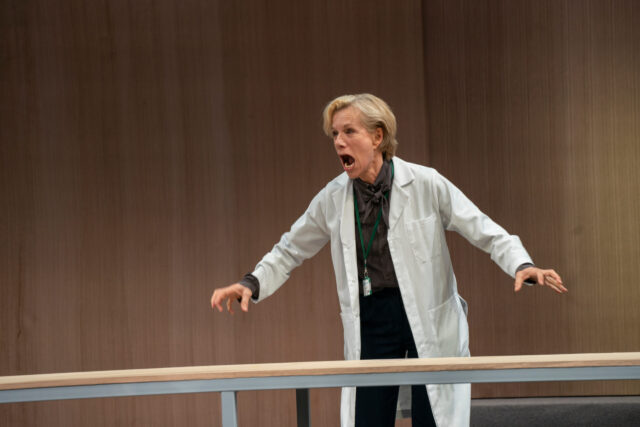

Juliet Stevenson delivers a ferocious performance of intense precision in The Doctor (photo by Stephanie Berger Photography / Park Avenue Armory)

THE DOCTOR

Park Ave. Armory, Wade Thompson Drill Hall

643 Park Ave. at Sixty-Seventh St.

Tuesday – Saturday through August 19, $54-$208

www.armoryonpark.org

“I’m a doctor,” neurosurgeon Ruth Wolff declares throughout Robert Icke’s The Doctor, while others keep categorizing her by her race, religion, gender, and sexual orientation. Identity politics and cancel culture collide in complicated ways with faith and medicine in the riveting play, which also takes on conscious and unconscious bias and the battle between science and religion, in a freely adapted update of Arthur Schnitzler’s 1912 Professor Bernhardi.

Wolff, portrayed by a fierce, unstoppable Juliet Stevenson with boundless energy, is the founding director of the Elizabeth Institute, a well-funded private facility that specializes in treating Alzheimer’s patients. Wolff is currently caring for Emily, a fourteen-year-old girl dying of sepsis after an unregulated abortion; when a priest, Father Jacob (John Mackay), arrives unannounced to deliver last rites, Wolff refuses him entry, stating that whether to receive his visit is Emily’s decision, not that of the priest or the girl’s parents, who are not immediately available.

“Let me make it clearer. Emily is gravely ill. Emily’s parents asked me to be here and to attend to her. Is that not obvious?” Father Jacob demands.

Wolff responds, “It’s obvious when the patient has requested religious assistance, because it’s written on her medical notes. In this instance, there’s nothing of the sort. . . . I have no way of knowing whether she last attended church in a Christening gown. The only thing of relevance is what she herself believes — and I don’t know. I don’t know if you’ve ever met her.”

As Father Jacob attempts to force his way into Emily’s room, Wolff blocks his way — there is some kind of physical confrontation, so cleverly staged that it is impossible to tell who might have struck whom. Emily then dies an awful death, and the characters choose sides based on their personal and professional beliefs, seeing what they want to see, as public pressure builds against Wolff.

The board of the Elizabeth Institute meet to decide the fate of their chair and director in Robert Icke’s The Doctor (photo by Stephanie Berger Photography / Park Avenue Armory)

Senior consultant and deputy director Robert Hardiman (Naomi Wirthner) views the complex situation as a chance to seize power. Dr. Michael Copley (Chris Osikanlu Colquhoun) displays full confidence in Wolff, but Dr. Paul Murphy (Daniel Rabin), putting faith before medicine, is insulted by what Wolff has done, declaring, “This is a Christian country.” Roberts (Mariah Louca), the press liaison who is Jewish, is having trouble dealing with the media, particularly as the religious angle grows more volatile.

Minister for Health Jemima Flint (Preeya Kalidas) expresses support for Wolff and dangles critical government financing if she apologizes. The new junior staff member (Jaime Schwarz) is generally bewildered by the controversy, suddenly learning that being a doctor is more than just treating patients. Professor Cyprian (Doña Croll) endorses everything Wolff did regarding Emily. Meanwhile, the search for a new head of pharmacology becomes an object lesson in decisions based on identity instead of merit.

Whenever she’s at home, Wolff is visited by Sami (Matilda Tucker), a high school student who lives upstairs. The two talk about sex, witches, and death. “We’re all going to die, though,” Sami posits. “Like — a sell-by date for your soul. It’s a ‘when’ not an ‘if.’ Could be tomorrow. Or tonight. In here. Now.”

Meanwhile, Wolff’s partner, Charlie (Juliet Garricks), mysteriously shows up at the institute, introducing each scene. “It might be the moment to bring me up,” Charlie offers. “At work? They don’t get my life. They don’t get to be involved,” Ruth responds. Charlie: “They don’t get to know about me.” Wolff: “What?” Charlie: “You know.” Wolff: “And why would I not talk about you?” Charlie: “Because you are ashamed of the way it makes you seem.” Wolff: “I go in tomorrow and start talking about you, now it’s going to seem like — like I’m asking for my ‘I’m a human too’ badge — some get me off the hook scheme. No. Not doing it.”

In the shorter second act, Wolff must defend herself on television, facing a panel of presumed experts spouting off about religion, abortion and medical ethics, Jewish history and culture, race and privilege, and bias. Wolff sits in a chair with her back to the audience as she is grilled, her face projected on two large screens, looming behind the pontificating blowhards in front of her. “My identity isn’t the issue,” she argues again and again, but no one is listening. Wolff refuses to see herself as a hero or a villain, but there are certain truths that she’s not listening to either.

Hildegard Bechtler’s set is a semicircular wooden wall that serves as a kind of protective barrier, keeping the characters trapped in rooms the way they are trapped by their minds, locked in judging others, with a turntable that rotates agonizingly slowly, unlike the wheels of justice in the court of public opinion; tables and chairs are moved around and Natasha Chivers’s lighting shifts intensity to signify changing from the institute’s bright conference room to Wolff’s much darker apartment. Bechtler also designed the costumes, primarily doctors’ white coats over everyday wear that tends toward black. Tom Gibbons’s sound design flows from board arguments to television show debate to intimate personal discussions, with Hannah Ledwidge adding drums and percussion from an open cube perched over the stage in the back.

Icke (Judas, Animal Farm) knows the Wade Thompson Drill Hall well, having previously presented Hamlet/Oresteia and Enemy of the People there in just the last two years, making fine use of the grand space. The show is extremely talky, with lots of explication and more than enough didacticism, particularly in the second act, and a late scene between Wolff and Father Jacob is sentimental overkill. In addition, during the TV segment, Wolff uses a racist word that ignites further altercation, but it feels forced to add unnecessary verbal fisticuffs.

The excellent cast challenges stereotypes and categorization by portraying characters that don’t look like them (except for Ruth and Flint); for example, whites play Blacks and women play men, although it is not immediately apparent. (Tucker is a standout as the unpredictable Sami.) In the script, Ickes notes, “Actors should be cast with and against the identity of the characters . . . other than in the debate section, where ideally the actors play with their identity. The design is that the audience have to reconsider characters once an aspect of their identity is revealed by the play.” It can get confusing, but that is part of the point, as Ickes lays the groundwork for people to stop classifying, and demonizing, people by race, gender, religion, et al.

But the show belongs to Emmy nominee and Olivier winner Stevenson (Truly, Madly, Deeply; Death and the Maiden), a veteran of the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Royal Court Theatre, and the National Theatre whose only previous North American stage appearance was as Desiree in a 2003 New York City Opera production of Stephen Sondheim’s A Little Night Music with Jeremy Irons, Claire Bloom, and Anna Kendrick. (Her extraordinary voice narrated Blindness through special headphones at the Daryl Roth two years ago.) Stevenson — Icke wrote the play with her in mind to be the star — is electrifying as Wolff, whether staring someone down, stating her case to doubters, or running around the room in a whirlwind of furious, uncontrollable energy. She stomps across the stage, firmly entrenched in Wolff’s repeated assertions that she is a doctor, justifying her decisions over and over again by adding, “I’m crystal clear.”

The Viennese Schnitzler (Liebelei, Reigen, Das weite Land) wrote dozens of plays, short stories, and novels that were ahead of their time, exploring sexual awareness, social convention, and anti-Semitism in ways that were controversial in his era but relate to what is happening in the twenty-first century. About midway through the first act, when Wolff explains to Copley and Murphy that she is not a practicing Jew, Murphy says, “But you would have been thought of as Jewish — in the 1940s.” She responds by getting to the heart of the story: “Maybe there might be more sensitive ways to reflect on the Jewish identity than the ones pioneered by the Nazis. Thank you, Michael, yes, you and I lost family in that war, and they had stars sewn onto their lapels, but their legacy is this: We now get to choose what defines us — so can we please get on with our lives.”

As we learn in The Doctor, that prescription is not so easy to fill.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]