Edward Hopper, Early Sunday Morning, oil on canvas, 1930 (Whitney Museum of American Art / © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper / Licensed by Artists Rights/Society, New York)

EDWARD HOPPER’S NEW YORK

Whitney Museum of American Art

99 Gansevoort St.

Through March 5, $18-$25

212-570-3600

whitney.org

Blockbuster solo exhibitions often elevate already famous artists to the next stratosphere, in the minds of the general public if not always the critics. Major shows spotlighting Rembrandt, Picasso, van Gogh, Matisse, Warhol, Basquiat, Magritte, Kusama, and others are events that draw enormous lines. People are traveling from around the world to see “Vermeer” at the Rijksmuseum, a collection of twenty-eight of the thirty-seven extant works attributed to the Dutch painter, the most ever on view in one show; however, be careful about planning your trip to Amsterdam, as it’s already sold out through its June 4 closing date.

What’s much harder to do is to humanize that superstar artist, but that’s exactly what the Whitney has done with “Edward Hopper’s New York,” an intimate and appealing exhibit that continues through March 5. Hopper has long been the centerpiece of the Whitney’s holdings, which comprise more than three thousand of his drawings, paintings, watercolors, letters, personal objects, photographs, film, and other paraphernalia. “Edward Hopper’s New York” has a razor-sharp focus on Hopper’s relationship with the city, where he began studying in 1899; he moved to New York in 1908, eventually settling in Washington Square in 1913, and married fellow artist Josephine Nivison in 1924. They had no children, instead concentrating on their work and going to the theater with a near-obsession.

The Whitney is packing them in in the fifth-floor galleries, in dramatic opposition to the works themselves, which mostly feature a single human figure, if any, and almost always modeled by his wife. The paintings are filled with a pervasive loneliness in a giant municipality re-created in Hopper’s imagination; this is no bustling Big Apple but rather a contemplative metropolis without skyscrapers or mass transit. (Even his canvases of bridges and railroad tracks are devoid of cars, buses, and trains.) Instead, the Nyack-born Hopper has transformed his longtime home into a vision of small-town America that could exist nowhere else. The paintings explore the often accidental formal beauty of the city’s built environment in their careful composition and sometimes surprising color juxtapositions.

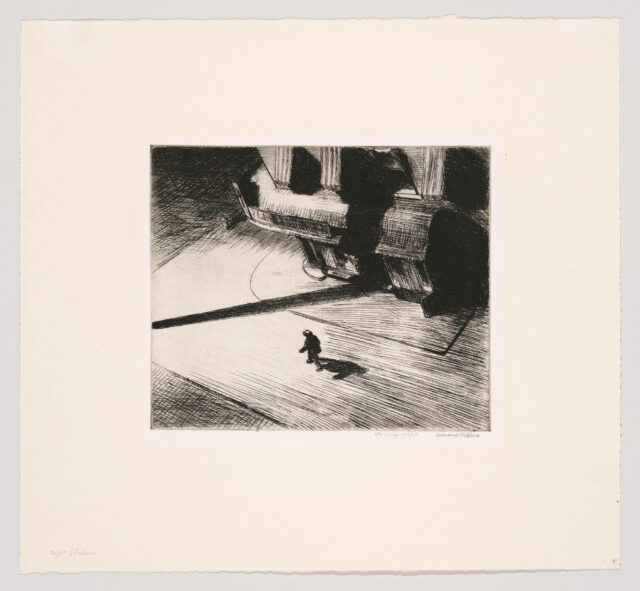

Edward Hopper, Night Shadows, etching, 1921 (Whitney Museum of American Art / © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper / Licensed by Artists Rights/Society, New York)

“Hopper’s New York was a product of his personal experiences in the city throughout his lifetime, of the particular ways that he engaged with the sites and sensations around him,” Whitney curator Kim Conaty writes in her catalog essay. “The painstaking deliberateness with which he absorbed, reflected upon, then refined his impressions — ‘I’m thinking out my picture,’ he once responded to a neighbor who approached him as he sat idly in the park — can be gleaned from his pace of output, which increasingly averaged but two or three canvases a year.” New York can be a push-push place, but the Hoppers were in no rush.

Divided into such sections as “Reality and Fantasy,” “The Window,” “The Horizontal City,” and “Theater,” the show comprises dozens of works that contain haunting, mysterious narratives. In Morning Sun, a woman sits on a bed, the light pouring in as she stares emptily out a window. In Morning in a City, a naked woman stands next to an unmade bed that is too small for her; she holds a piece of clothing and looks out a window for something or someone missing.

In New York Movie, a woman in a blue outfit with a red stripe running down the side, most likely an usher, stands against the wall at the right, a hand on her chin, deep in thought; at the left, we can see only a few rows in the movie theater and a sliver of the black-and-white film, with only two people in the audience, the lush red velvet seats and a touch of blue echoing the usher and the entrance curtain, casting the picture in an elegant loneliness.

In Early Sunday Morning, one of the grandest American works of the twentieth century, a glowing light casts long shadows across an empty sidewalk in front of a two-story building, including, impossibly, a blue one emanating from a gray fire hydrant; the first-floor storefronts are closed, the second filled with windows, some partially covered with yellow shades. It was based on a scene from Elmer Rice’s 1929 Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Street Scene, expanded from Rice’s earlier Sidewalks of New York. “There was neither plot nor situation,” Rice told the New York Times that February. “One merely saw the house shaking off its sleep and beginning to go about the business of the day.” That is precisely what Hopper captures, in that and so many other paintings.

Edward Hopper, New York Movie, oil on canvas, 1939 (Museum of Modern Art/ © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York / image courtesy Art Resource)

The Hoppers were avid theatergoers, which is creatively displayed in an installation that includes dozens of ticket stubs they saved, along with a small notebook detailing the shows they saw, accompanied by projections of photographs of the theaters they went to and scenes from the productions they took in. They generally paid $1.10 for balcony seats for such plays as An American Tragedy, Pygmalion, The Front Page, and Dead End; they splurged for $3.30 orchestra seats for Hamlet with John Gielgud, as Hopper noted on the back of the stub from November 24, 1936. The vitrine also shines a light on Hopper’s numerous works that are set inside theaters.

Another section traces the Hoppers’ attempt to combat the potential intrusion of New York University into the serenity of Washington Square Park, the neighborhood where Hopper moved to in 1913 and lived the rest of his life. Amid such works as Skyline Near Washington Square, the charcoal drawing Town Square (Washington Square and Tower), and Roofs, Washington Square is a glass case that highlights an exchange of letters between Hopper and Parks Commissioner Robert Moses. The room also focuses on Edward’s relationship with Jo, pointing out that when she posed for him, they would often create fictional characters and situations, role-playing. Several watercolors by Jo are on view as well as a charming short video of them both working in their home studio.

Lovingly curated by Conaty, the show welcomes viewers into the Hoppers’ world like no other solo exhibition I can recall; there’s a constant chatter in the galleries by New Yorkers and tourists alike discussing the paintings and the city with enthusiasm, regardless of their prior knowledge of art or Manhattan. The works have a way of uniting everyone at the Whitney, perhaps in part as a response to the loneliness depicted in so many of the canvases (and in real life during the pandemic lockdown). “Edward Hopper’s New York” might not be an exact replica of the city, but it gracefully represents the town we savor every day.