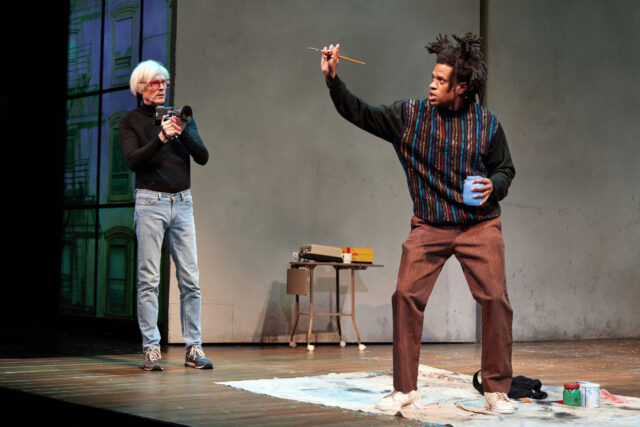

Andy Warhol (Paul Bettany) and Jean-Michel Basquiat (Jeremy Pope) collaborate in new Broadway play (photo by Jeremy Daniel)

THE COLLABORATION

Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

261 West Forty-Seventh St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through February 11, 474-$318

www.manhattantheatreclub.com

In the fall of 1985, gallerist Tony Shafrazi and art dealer Bruno Bischofberger presented “Warhol Basquiat: Paintings” on Mercer St., an exhibition of works made in tandem by Pop Art maestro Andy Warhol, looking to restore himself to relevance, and rising street-art superstar Jean-Michel Basquiat, who wanted to reach the next level of fame and fortune. The story of this unusual alliance is told in Anthony McCarten’s boldly titled The Collaboration, extended through February 11 at Manhattan Theatre Club’s Samuel J. Friedman Theatre.

While Basquiat and Warhol’s teaming up might have been a lightning strike of an idea in the art world, it’s more than a bit presumptuous to declare that it was the collaboration; if you didn’t know what the play was about, the title wouldn’t make you first think of this unexpected partnership. That aside, it was a fascinating moment in art history, and just as the collaboration was not wholly successful, so goes The Collaboration on Broadway.

In September 1985, Vivian Raynor wrote about the exhibit in the New York Times, “It’s a version of the Oedipus story: Warhol, one of Pop’s pops, paints, say, General Electric’s logo, a New York Post headline, or his own image of dentures; his twenty-five-year-old protege adds to or subtracts from it with his more or less expressionistic imagery. The sixteen results — all ‘Untitleds,’ of course — are large, bright, messy, full of private jokes, and inconclusive.” The same can be said of the play itself.

Alternatively, artist Keith Haring wrote in “Painting the Third Man” in 1988, “Jean-Michel and Andy achieved a healthy balance. Jean respected Andy’s philosophy and was in awe of his accomplishments and mastery of color and images. Andy was amazed by the ease with which Jean composed and constructed his paintings and was constantly surprised by the never-ending flow of new ideas. Each one inspired the other to outdo the next. The collaborations were seemingly effortless. It was a physical conversation happening in paint instead of words. . . . For me, the paintings which resulted from this collaboration are the perfect testimony to the depth and importance of their friendship. The quality of the painting mirrors the quality of the relationship. The sense of humor which permeates all of the works recalls the laughter which surrounded them while they were being made.”

Meanwhile, poet, songwriter, and playwright Ishmael Reed offered little love for Warhol in his recent show, The Slave Who Loved Caviar, feeling that Warhol treated Basquiat like a mascot; Reed wrote, “As Basquiat, the Radiant Child of the downtown art scene of the 1980s, was sacrificed to sustain the dying career of a fading Super Star, Antonius was sacrificed so that Hadrian would recover from a mysterious illness.”

Andy Warhol (Paul Bettany) films Jean-Michel Basquiat (Jeremy Pope) in The Collaboration (photo by Jeremy Daniel)

Part of McCarten’s Worship Trilogy, which also includes The Two Popes and Wednesday at Warren’s, Friday at Bill’s, The Collaboration takes place alternately in Bischofberger’s (Erik Jensen) Manhattan gallery, Warhol’s (Paul Bettany) studio near Union Square, and Basquiat’s (Jeremy Pope) loft apartment and studio on Great Jones St. At first both artists are hesitant to work together; being shown Basquiat’s paintings for the first time by Bischofberger, Warhol, referring to them as “art therapy things,” says, “They’re so . . . busy. Is it too much? Or am I getting old? And so much anger. All these skulls and gravestones everywhere. I thought I was bleak. And all these words and symbols, what’s it all mean? What’s he trying to say? Bruno? Do you know? And why do they have to be so ugly? Did he tell you? Does he talk about that? They’re so ugly and angry and yeah, well, they’re kinda violent. I’d be careful; he’s really in trouble, I think.”

Basquiat is also unsure of the potential partnership, telling Bischofberger, “I’m better than Andy. I don’t need this. . . . And how come he doesn’t paint anymore, you know? Just mechanically reproduces all these prints? There’s no soul. I’m Dizzy Gillespie, blowing a riff, he’s one of those pianos that plays all by itself. The same tune. Over and over. You seen those things? Pink, pink plonk, pinkety pinkety pink.”

Bischofberger, who represents both artists, promises Warhol, “It will be the greatest exhibition ever in the history of art.” Warhol says, “Please don’t exaggerate.” The dealer boasts, “Warhol versus Basquiat.” The Pop maestro wonders, “Oh, versus? Gee, you make it sound so macho, like a contest. I don’t know. I thought you said it would be a collaboration?” Bischofberger answers, “Painters are like boxers; both smear their blood on the canvas.” The promotional posters for the exhibition — which eventually will become more famous than the actual works (one of the original posters hangs in my apartment) — feature Warhol and Basquiat wearing boxing gloves, ready to do battle.

But soon the soft-spoken Warhol, who hadn’t picked up a paintbrush in more than twenty years but has amassed a fortune through his silkscreens, photography, films, and business savvy, is creating canvases with Basquiat, who is far more spontaneous and unpredictable, taking drugs, sleeping around (Krysta Rodriguez plays Maya, a fictionalized version of Basquiat’s girlfriend Suzanne Mallouk), and keeping his cash in the refrigerator.

Once the playwright finally gets Andy and Jean putting paint to canvas, their debates about the purpose of art sound a bit sanctimonious. No one knows what their conversation was really like: Within three years, they would both be dead, Basquiat in 1987 at the age of twenty-seven, Warhol in 1988 at the age of fifty-eight.

Directed by Kwame Kwei-Armah (Things of Dry Hours, One Night in Miami), The Collaboration works best when Warhol and Basquiat get down to brass tacks, exploring what they might do together, each suspicious of the other’s motives and abilities. In roles previously played by David Bowie and Jeffrey Wright, respectively, in Julian Schnabel’s 1996 film, Basquiat (Dennis Hopper was Bischofberger), Bettany (Love and Understanding, WandaVision) and Tony nominee Pope (Choir Boy, Ain’t Too Proud) are phenomenal. Pope embodies Basquiat’s untethered energy, his lust for life, and his social conscience, particularly when learning that his friend, graffiti artist Michael Stewart, is in the hospital after an altercation with the police. Bettany not only looks great in Warhol’s trademark white fright wig and black turtleneck and sneakers (the wigs are by Karicean “Karen” Dick and Carol Robinson, with sets and costumes by Anna Fleischle) but captures his awkward, strange public persona.

Rodriguez (Into the Woods, Seared) does what she can as the underwritten Maya, an amalgamation that stretches the truth of Basquiat’s relationships with women, and Jensen (Disgraced, How to Be a Rock Critic) provides a solid middle ground to highlight the disparity between his two artists.

Andy Warhol (Paul Bettany) watches Jean-Michel Basquiat (Jeremy Pope) paint in The Collaboration (photo by Jeremy Daniel)

The narrative takes a sharp turn beginning at intermission, when large monitors just outside both sides of the stage show footage of Bettany’s Warhol and Pope’s Basquiat collaborating, painting on transparent glass, mimicking the style Warhol uses when filming Basquiat on his 16mm spring-wound Bolex movie camera. As they did prior to the beginning of the show, DJ theoretic spins thumping 1980s music from a booth on the stage as the prerecorded film plays.

During the second act, Kwei-Armah and McCarten, who has written such fact-based films as The Theory of Everything, Darkest Hour, and Bohemian Rhapsody and the book for the current Neil Diamond musical A Beautiful Noise, become obsessed with Warhol’s live footage of Basquiat (the projections are by Duncan McLean), so it’s hard to know where to look. (Oh, what Ivo van Hove has wrought.) A notoriously private person despite his fondness for late-night celebrity-studded parties, Warhol wants to capture the real Basquiat on film, but Basquiat doesn’t want to be seen as a commodity. This dichotomy further emphasizes the difference, and psychological distance, between Basquiat and Warhol, whose shows are still blockbusters today. (For example, Basquiat’s biographical “King Pleasure” in Chelsea last year and the Whitney’s 2018-19 “Andy Warhol — From A to Be and Back Again.”

None of Warhol’s footage exists today, so we don’t know what really happened, but what McCarten and Kwei-Armah depict grows more confusing and annoying by the second. We also don’t see enough of the artists’ collaboration itself, but that output is not considered among either one’s most well regarded works. Alas, the same can be said of the creators of the play. But as Warhol explains to Basquiat, “I don’t think there’s going to be a revolution, but if there is it will be televised, with commercial breaks, cause it’s all about brands now. Even us, we’re not painters, we’re brands. Jean. We’re brands. Well, you’re almost a giant brand, and after this exhibition with me you will be too. Then just watch the language change, Jean.”

The Collaboration concludes on the same note as Eduardo Kobra’s large-scale 2018 mural in Chelsea above the Empire Diner, a reimagined Mount Rushmore with the faces of Andy Warhol, Frida Kahlo, Keith Haring, and Jean-Michel Basquiat, all of whom remain brands to this day.