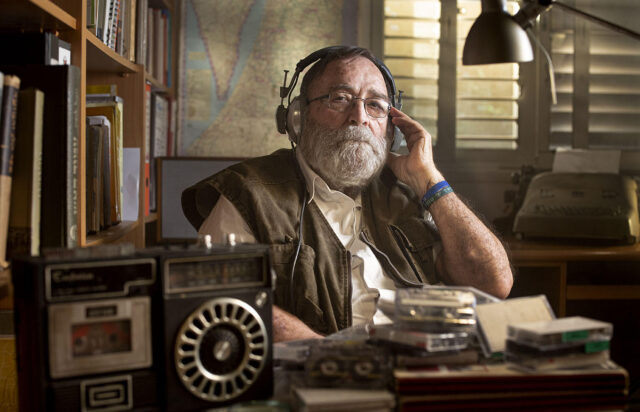

Teddy Katz listens to damning audiotapes about a 1948 massacre in Tantura

TANTURA (Alon Schwarz, 2022)

IFC Center

323 Sixth Ave. at West Third St.

Opens Friday, December 2

212-924-7771

www.ifccenter.com

There’s a deeply disturbing theme that runs through Alon Schwarz’s shocking, must-see documentary, Tantura, about one specific incident during what Palestinians refer to as Al Nakba, “the Catastrophe” that took place during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war.

In the late 1990s, a graduate student named Teddy Katz researched a possible Israeli army massacre that occurred in the Palestinian village of Tantura. When filmmaker Schwarz interviews members of Israel’s Alexandroni Brigade about it, they smile and laugh as they either flat-out deny that such war crimes happened or basically tell Schwarz, so what if it did?

“In the War of Independence, we knew one simple thing: It’s either me or them,” Amitzur Cohen says. “What would I tell [my wife]? That I was a murderer?” he easily admits with a laugh. “If you killed, you did a good thing,” Hanoch Amit says with a smile. Henio-Tzvi Ben Moshe, head of the Alexandroni Veteran’s Association, lets out a disturbing laugh when he declares, “We’re done with Teddy Katz.”

In the late 1990s, for his master’s thesis at the University of Haifa, Katz interviewed 135 people about the massacre, compiling 140 hours of recordings about the Tantura atrocities, centered around the alleged cold-blooded murder of some two hundred Palestinians whose bodies were then dumped into a mass grave. He received a high grade on the paper, but it was soon submerged in controversy, resulting in a defamation lawsuit and claims that it was all a lie.

“You can take the tapes and listen to them, but if you want to make a movie out of it, be careful, because you’ll be hunted down like I was,” Katz tells Schwarz.

But that warning doesn’t deter Schwarz, who speaks with Alexandroni Brigade vets — who are now in their nineties — university professors, engineers, and Arabs who survived the massacre as he puts together what actually happened at Tantura and how Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion began the cover-up, which is still going on.

“My whole life I thought, and I still think, that the root of the disaster, including the part . . . that can be called the contamination, is 1948,” explains Katz, who was named after Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism. “To this day the vast majority of what happened in 1948 is not only hushed up but also destroyed.”

Schwarz intercuts archival footage from the war — in which hundreds of Palestinian towns and villages were demolished and some three quarters of a million refugees fled their homes — with scenes from a staged propaganda reenactment and clips of Ben-Gurion and the establishment of the State of Israel. As the evidence mounts, so does the refusal to acknowledge the Catastrophe.

“It’s forbidden to tell. I’m not going to talk about it . . . because . . . it could cause a huge scandal. I don’t want to talk about it,” brigade vet Yossef Diamant says. “That’s it. But it happened; what can you do? It happened. . . . [Katz] told the truth,” he adds with a dismissive laugh.

Casually sitting in a chair outside with a woman on either side of him, Mulik Sternberg proudly says, “The Arabs are an evil, cruel, vindictive enemy, but we were better, in battle. Always. . . . Of course we killed them. We killed them without remorse.” He is clearly unafraid of any possible repercussions.

Mustafa Masri, who lives in Fureidis, where many of the Tantura survivors were relocated, describes seeing the bodies of his murdered father and brother piled on a cart of victims. Professor Yoav Gelber comes right out and says, “I don’t believe witnesses.”

Professor Ilan Pappe puts it all in perspective when he says, “I think the self-image of Israel as a moral society is something I haven’t seen anywhere else in the world. How important it is to be exceptional. We are the Chosen People. This is part of the Israeli self-identification as a very superior moral people. . . . I think it’s very hard for Israelis to admit that they commit war crimes.”

Schwarz is an Israeli-born Jew who worked as a high-tech software entrepreneur before turning to documentaries, making Narco Cultura and Aida’s Secrets with his brother Shaul. Alon, who considers himself “a member of the moderate left side of Israel’s political system,” initially set out to make a film about young human rights activists who are trying to end the 1967 occupation and are labeled by many as traitors — much as Katz is. Schwarz stumbled on Katz’s dilemma by accident.

Documentary seeks to uncover the truth of what happened in Tantura in May 1948

Schwarz is no mere fly on the wall in the film but is actively investigating numerous aspects of the case, putting himself in the story. Tantura is reminiscent of Joshua Oppenheimer’s 2012 The Act of Killing and 2014 follow-up, The Look of Silence, as the director confronts the perpetrators of the 1965–66 genocide in Indonesia, who are proud of what they did. It also recalls the 1968 Mỹ Lai massacre led by US Lt. William Calley Jr. in Vietnam.

Katz, who has had three strokes and uses a motorized scooter to get around, is determined to not give up until justice wins out, despite all that’s happened to his career and his family. “You feel like the country is against you,” his wife, Ruth, tells Schwarz. But none of it might matter in the long run.

“What we remember are the good memories,” says Drora Varblovsky, one of four remaining original residents of Kibbutz Nachsholim, which was started in June 1948 on the former site of Tantura.

“Yes, exactly. I have only good memories,” Tereza Carmi adds. “Because I’m fed up with remembering bad things.”

Tantura opens at IFC on December 2, with Schwarz on hand for Q&As after the 7:50 shows on December 2 and 3.