Nina Menkes delves into such films as The Lady from Shanghai in Brainwashed

BRAINWASHED: SEX-CAMERA-POWER (Nina Menkes, 2022)

DCTV’s Firehouse Cinema

87 Lafayette St.

Opens Thursday, October 20

firehouse.dctvny.org

www.brainwashedmovie.com

In his seminal 1972 book Ways of Seeing, British essayist, novelist, and cultural thinker John Berger writes, “According to usage and conventions which are at last being questioned but have by no means been overcome, the social presence of a woman is different in kind from that of a man. A man’s presence is dependent upon the promise of power which he embodies. . . . The promised power may be moral, physical, temperamental, economic, social, sexual — but its object is always exterior to the man. A man’s presence suggests what he is capable of doing to you or for you. . . . By contrast, a woman’s presence expresses her own attitude to herself, and defines what can and cannot be done to her. Her presence is manifest in her gestures, voice, opinions, expressions, clothes, chosen surroundings, taste — indeed there is nothing she can do which does not contribute to her presence. Presence for a woman is so intrinsic to her person that men tend to think of it as an almost physical emanation, a kind of heat or smell or aura.”

American filmmaker Nina Menkes forever changes the way you’ll see and experience movies in her eye-opening documentary Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power. “As a filmmaker and as a woman, I found myself drowning in a powerful vortex of visual language from which it is very difficult to escape,” she explains at the beginning of the film, an adaptation of her illustrated lecture “Sex and Power: The Visual Language of Oppression.” Producer and director Menkes, whose filmography includes Queen of Diamonds, Magdalena Viraga, and Dissolution, speaks with sixteen women and two men and shows clips from more than one hundred and twenty-five films as she reveals how much the movie industry is reliant on the male gaze, creating fantasy spaces that celebrate men while objectifying women.

Dartmouth filmmaker and faculty member Iyabo Kwayana posits, “I think we have to consider that it is through the formal visual language that we are effectively communicating meaning, and we inherit so much subliminally that comes from this language and it has to do with how shots are composed and framed, how they’re assembled and ordered in a sequence of shots. All of that becomes the grammar and syntax by which meaning is conveyed to a viewer. So in a visual culture such as ours, in which there is a ravenous appetite towards the female as object, if the camera is predatory, then the culture is predatory as well.”

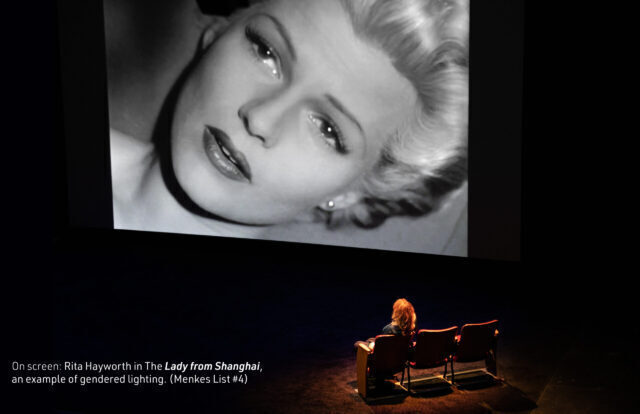

Menkes divides her talk into five sections that comprise what she calls “The List”: “Subject/Object,” “Framing,” “Camera Movement,” “Lighting,” and “Narrative Position.” Among the films she examines are The Lady from Shanghai, Super Fly, Contempt, Carrie, Lost in Translation, Cuties, Crazy Rich Asians, Sleeping Beauty, Do the Right Thing, Blade Runner 2049, and The Silence of the Lambs, revealing how ingrained it is to depict men and women differently, what Transparent producer, writer, and director Joey Soloway calls “propaganda for patriarchy.” Director and activist Maria Giese adds, “Hollywood has been the worst violator of Title VII [part of the 1964 Civil Rights Act] of any industry in the United States — even worse than coal mining.”

Actress Rosanna Arquette shares the abuse she suffered at the hands of Harvey Weinstein as well as the regrets she has about a nude scene she did in After Hours. Menkes includes nude scenes throughout the film, involving Brigitte Bardot, Jane Fonda, Nicole Kidman, and many other familiar stars, describing how they can be “attacks on our selfhood.” She demonstrates how the use of slow motion focuses on a woman’s erotic sensuality but a man’s power and violence. Menkes also explores how the depiction of women on celluloid impacts sexual abuse.

Global Media Center for Social Impact founder Sandra de Castro Buffington asks, “How is rape culture normalized? There are really three key elements that we see on the screen and in real life. One is the objectification of women’s bodies. Another is the glamorization of sexual assault, especially on the screen. And the third is disregard for women’s rights and safety, even if a hand is not laid on another person. These are all of the elements that create an environment that allows one group to gain and maintain power over another.”

California State University faculty member Rhiannon Aarons expounds, “I think this visual language really contributes to female self-hatred and insecurity in a way that is not insignificant. What is normalized as beauty is really seen specifically and dominantly through a male gaze. I think that really changes how we relate in the world in general and not necessarily in the best way.”

Menkes spends extra time delving into such films as Raging Bull, Bombshell, and Mandingo, demonstrating how women’s voices are silenced and power dynamics are ingrained in visual storytelling. She uses a critical scene from Portrait of a Lady on Fire to display how director Céline Sciamma exposes that subject-object power dynamic and turns it around. Among the other women providing important insight are psychoanalyst Dr. Sachiko Take-Reece, writer Jodi Lampert, UCLA Film and Television Archive director May Hong HaDuong, intimacy coordinator Ita O’Brien, producer-director Amy Ziering, cinematographer Nancy Schreiber, author Maya Montanez Smukler, film theorist Laura Mulvey, filmmakers Julie Dash, Eliza Hittman, Catherine Hardwicke, and Penelope Spheeris, and foley artist and activist Lara Dale, who said no to sexual exploitation, effectively ending her career as an actress. Two snippets from a “Sex and Power Talk Discussion” at the California Institute of the Arts feel extraneous, but every other minute of Brainwashed is riveting.

The film is insightfully edited by Cecily Rhett and smartly shot by Shana Hagan, with a compelling score by Sharon Farber; Menkes purposely hired women to head the major departments, something she points out that Oscar-winning director Kathryn Bigelow did not do on The Hurt Locker.

Reflecting on her 2007 feature Phantom Love, Menkes says, “All of my own narrative fiction films have been centrally concerned with expressing the abject feminine — and the wound that is carried deep inside.” We still have a long way to go to heal that wound, but Brainwashed sets us on a path to affect the way we see and interpret cinema. As actor and comedian Charlyne Li tells us, “There’s a saying that people say that if people were to get rid of all the sexual predators that there would be no film industry.”

Brainwashed opens October 20 at DCTV’s Firehouse Cinema, with Q&As with Menkes at the 7:00 screenings on October 20 (moderated by critic and podcaster Violet Lucca) and October 21 and with Geise and director and programmer Dara Messinger on October 22.