Alan Cumming channels Scots poet Robert Burns at the Joyce (photo by Tommy Ga-Ken Wan)

BURN

The Joyce Theater

175 Eighth Ave. at Nineteenth St.

September 21-25, $76-$106

www.joyce.org

Quite by coincidence, the last three shows I’ve seen were all solo plays featuring award-winning performers, three very different productions that run the gamut of what one-person shows can be. Two were based on real people while the third is a work of imaginative fiction, and all three take unique approaches to narrative storytelling and staging.

Continuing at the Joyce through September 25, Alan Cumming and Steven Hoggett’s Burn is an inventive and exciting piece of dance theater that takes the audience inside the head of Scottish poet Robert Burns (née Burnes). Tony and Olivier winner Cumming portrays Burns, the author of such poems as “Auld Lang Syne,” “Scots Wha Hae,” “Tam o’ Shanter,” and “A Red, Red Rose,” as a delightfully impish ghoul in goth-clown makeup and attire. (The cool costumes are by Katrina Lindsay). Hoggett and Cumming follow Burns from his birth in January 1759 to his death in July 1796 at the age of thirty-seven; the text comes primarily from Burns’s poems and letters.

“Here am I,” Burns says at the start. “You have doubtless heard my story, heard it with all its exaggerations. But I shall just beg a leisure moment of you until I tell my own story my own way. My name has made a small noise in this country, but I am a poor, insignificant devil, unnoticed and unknown. I have been all my life one of the rueful looking, long visaged sons of Disappointment. I rarely hit where I aim, and if I want anything I am almost sure never to find it where I seek it.”

Alan Cumming and Steven Hoggett’s Burn is a multimedia wonder (photo by Tommy Ga-Ken Wan)

The son of a gardener and failed farmer, Burns suffered from hypochondria and anxiety, turning to poetry in his teen years. Sitting at a desk, he explains, “My way of poesy is: I consider the poetic sentiment, then choose my theme, begin one stanza, when that is composed — which is generally the most difficult part of the business — I walk away.” As he walks away, the quill pen keeps on writing, the first of several illusions that bring a magical quality to the tale. Ana Inés Jabares Pitz’s spare set consists of a desk and a few chairs, all of which hold surprises.

Burns shares his romantic philandering, talking to ladies’ shoes that dangle from the ceiling. A seeming pile of garbage transforms into a glowing white dress that floats in the air. Andrzej Goulding’s projections on the back wall begin with a dark and ominous thunderstorm, accompanied by Matt Padden’s eerie sounds and Tim Lutkin’s stark lighting, and also include Burns’s handwriting, shots of the Scottish mountains partially hidden by clouds (and fog that seeps onto the stage), and dark images evocative of early experimental cinema that explored the celluloid filmstrip itself.

The fifty-seven-year-old Cumming (Cabaret, Macbeth) is his charmingly sly self in the role, occasionally breaking out into short stretches of choreographed movement (by Hoggett and Vicki Manderson), during which his dialogue is prerecorded. The score consists of several of British composer Anna Meredith’s pulsating electronic landscapes (“Solstice,” “HandsFree,” “Calion,” Descent,” “Return”). There is always something to see and hear; the work is in constant motion, never slowing down for a second. It’s a marvel of timing as all the elements come together in a well-paced sixty-five minutes.

At one point, Burns tells us that his motto is “I dare!” That holds true for Cumming and Hoggett with Burn, which deserves a longer run.

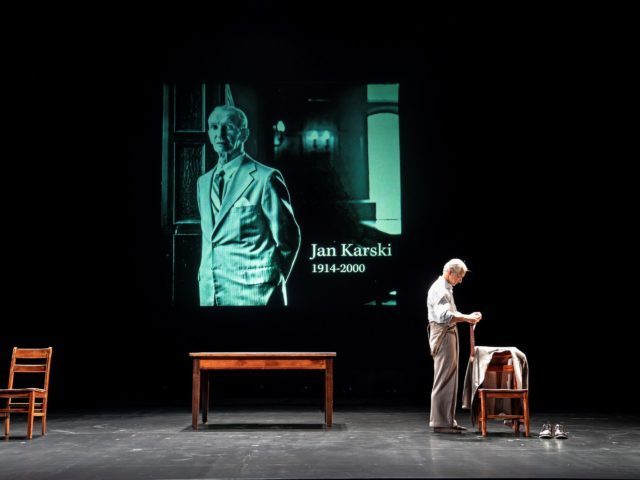

David Strathairn portrays Jan Karski and others in Holocaust tale (photo by Rich Hein)

REMEMBER THIS: THE LESSON OF JAN KARSKI

Theatre for a New Audience, Polonsky Shakespeare Center

262 Ashland Pl. between Lafayette Ave. & Fulton St.

Wednesday – Sunday through October 16, $97

866-811-4111

www.tfana.org

Like Cumming in Burn, Oscar nominee and Emmy winner David Strathairn plays a real person in Clark Young and Derek Goldman’s sharply drawn Remember This: The Lesson of Jan Karski, at Theatre for a New Audience’s Polonsky Shakespeare Center through October 16. But in this case, we know what Karski, born Jan Romuald Kozielewski in Łódź, Poland, in 1914, looked and sounded like.

The play begins with a prologue in which Strathairn explains, “We see what goes on in the world, don’t we? Our world is in peril. Every day, it becomes more and more fractured, toxic, seemingly out of control. . . . We see this, don’t we? How can we not see this? So, what can we do?” He concludes, “Human beings have infinite capacity to ignore things that are not convenient.”

We then see a projection of a scene from Claude Lanzmann’s epic Shoah documentary. He is interviewing Karski, who gets choked up and leaves the room, walking down a narrow hallway. As he returns in the documentary, Strathairn takes his place onstage, emerging as Karski, ready to proceed with his harrowing, all-too-true tale. He refers to himself as “the man who told of the annihilation of the Jewish people while there was still time to stop it.” He was a witness, hence Lanzmann’s interest in filming him.

Karski goes back to his childhood, explaining how his mother, a devout Catholic, taught him to treat everyone the same, especially the Jews, who were harassed by other kids. He was groomed to become a statesman from an early age; he in fact became a Polish diplomat before teaching law at Georgetown for forty years.

A soft-spoken, humble gentleman, Karski had not planned on becoming a hero, and he did not want to be celebrated as one. “I was forgotten, and I wanted to be forgotten,” he says. But he at last shared his story, and it is a thrilling yet tragic one. He is recruited by the Polish resistance and goes to Auschwitz, sending secret messages about the horrors that are happening in Eastern Europe. He ultimately brings his case to several of the most prominent and powerful men in the United States, but we all know how they reacted.

Jan Karski (David Strathairn) is a witness the powers that be won’t listen to in Remember This (photo by Rich Hein)

Calm and composed, Strathairn portrays dozens of characters in the show, from his grandmother, his mother, Lanzmann, Hermann Goering, Polish officers, Russian guards, and Polish prisoners to his sister-in-law, Nazis, a teacher, a priest, a nurse, and such Jewish leaders as Szmul Zygielbojm. (“Remember his name. This man loved his people more than he loved himself. Zygielbojm shows us this total helplessness, the indifference of the world,” Karski says.)

Strathairn (Nomadland; Good Night, and Good Luck) adopts slightly different accents for each character but doesn’t change his costume (by Ivania Stack), an earth-toned suit with suspenders and a button-down sweater vest; throughout the play, he takes his jacket, shoes, and vest off, adjusts his suspenders, puts his jacket, shoes, and vest back on, or just buttons and unbuttons the jacket and vest seemingly at random, but these small movements, seemingly insignificant as they relate to the story, are mesmerizing.

Misha Kachman’s simple set is just a table and a few chairs, not unlike that of Burn, with Zach Blane’s lighting and Roc Lee’s sound adding layers of depth at certain moments. They all come together to depict Karski diving out of a moving train, a stunt pulled off by the seventy-three-year-old Strathairn, who jumps off the table and rolls across the floor.

Written by Young and Goldman and directed by Goldman, the ninety-minute Remember This was originally created by the Laboratory for Global Performance and Politics at Georgetown; fortunately, it does not get bogged down in merely educating the audience but maintains a gripping pace, although the frame intro and conclusion are essentially unnecessary. (There will be TFANA Talks featuring such guests as Bianca Vivion Brooks, Joshua Harmon, Benjamin Carter Hett, and Jerry Raik following the Sunday matinees on September 25 and October 2.) All these years later, it’s still infuriating that America, a land of immigrants, turned its back on the Jews and what became the Holocaust, only entering the war after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

“I report what I see,” Karski, who was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama in 2012, repeats. If only the powers that be listened to him. He might call himself “an insignificant little man,” but Strathairn and Remember This prove him to be so much more.

But in the end, it might be the words of Zygielbojm that pertain closest to what is happening today across the globe: “Madness, madness, madness. They are mad, they are mad. The whole world is mad. . . . This is a mad world. I have to do . . . I don’t know what to do . . . So what do I do?”

David Greenspan plays sixty-six roles in one-man Gertrude Stein adaptation

FOUR SAINTS IN THREE ACTS

The Doxsee @ Target Margin Theater

232 52nd St., Brooklyn

Thursday – Sunday through October 9, $15-$35

212-924-2817

lortel.org

In 1927, soon-to-be literary giant and art collector Gertrude Stein wrote the libretto for composer Virgil Thomson’s 1928 opera, Four Saints in Three Acts. It was a dizzying barrage of words for sixty-six characters, filled with nonsense sentence fragments, inexplicable repetition, and mini-explosions of numbers.

Six-time Obie winner David Greenspan completes his solo trilogy, which began with Barry Conners’s The Patsy and Eugene O’Neill’s Strange Interlude, with a frenetic adaptation of Stein’s libretto, with Greenspan performing every role while not cutting a word from Stein’s original. Just as Cumming embodied Burns and Strathairn manifested Karski, Greenspan fully inhabits Stein’s complex dialogue.

A Lucille Lortel Theatre production running through October 9 at the Doxsee @ Target Margin Theater in Sunset Park, Four Saints is no traditional narrative. In fact, it is almost impossible to know what is going on at any moment; there is no real plot. Instead, it is all about the beauty and rhythm of language and poetry amid the mystery of religious saints.

In 1989, shortly before his death, Thomson wrote in the New York Review, “Curiously enough, British and American ways in both speech and movement differ far less on the stage, especially when set to music, than they do in civil life. Nevertheless, there is every difference imaginable between the cadences and contradictions of Gertrude Stein, her subtle syntaxes and maybe stammerings, and those of practically any other author, American or English. More than that, the wit, her seemingly endless runnings-on, can add up to a quite impressive obscurity. And this, moreover, is made out of real English words, each of them having a weight, a history, a meaning, and a place in the dictionary.”

In a ninety-five-minute tour-de-force performance, the sixty-six-year-old Greenspan gives equal weight to every word he speaks, using various accents and hand movements for different characters. (Saint Chavez, for example, is always identified by bringing his hands together as if holding a baseball bat, reminding me of Hollis Frampton’s Zorn’s Lemma, which creates its own verbal and visual alphabet.) Greenspan moves across a large rug on a platform stage, surrounded on three sides by gentle off-white curtains, portraying such characters as commère, Saint Therese, Saint Martyr, Saint Settlement, Saint Thomasine, Saint Electra, Saint Wilhelmina, Saint Evelyn, Saint Pilar, Saint Hillaire, Saint Bernadine, and compère. (The set and lighting are by Yuki Nakase Link.)

David Greenspan goes it alone in Four Saints in Three Acts at the Doxsee

He says, “Saint Therese seated and not standing half and half of it and not half and half of it seated and not standing surrounded and not seated and not seated and not standing and not surrounded not not surrounded and not not not seated not seated not seated not surrounded not seated and Saint Ignatius standing standing not seated Saint Therese not standing not standing and Saint Ignatius not standing standing surrounded as if in once yesterday. In place of situations.”

He explains, “A scene and withers. Scene Three and Scene Two. This is a scene where this is seen. Scene once seen once seen once seen.”

He expresses, “Once in a while and where and where around around is as sound and around is a sound and around is a sound and around. Around is a sound around is a sound around is a sound and around. Around differing from anointed now. Now differing from anointed now. Now differing differing. Now differing from anointed now. Now when there is left and with it integrally with it integrally withstood within without with drawn and in as much as if it could be withstanding what in might might be so.”

He opines, “Across across across coupled across crept a cross crept crept crept crept across. They crept across.”

Directed by Ken Rus Schmoll (The Invisible Hand, The Internationalist), Four Saints in Three Acts is more than just a flight of fancy; it’s a celebration of language, and of Stein’s radicalism. It doesn’t have the straightforward narrative of Remember This or the special effects of Burn, but it does sing with its own cadence and rhythm, anchored, as in all three plays, by a stellar solo performance.