Los Angeles Plays Itself looks at LA as a character in the movies

MOVIETOWN: LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF AND OTHER LA VISIONS

IFC Center

323 Sixth Ave. at West Third St.

July 15-28, $17 per film, 3-pack $42, 5-pack $60

212-924-7771

www.ifccenter.com

“This is the city: Los Angeles, California. They make movies here. I live here,” Thom Andersen says in his groundbreaking 2003 documentary, Los Angeles Plays Itself. “Sometimes I think that gives me the right to criticize the way movies depict my city. I know it’s not easy — the city’s big; the image is small. It’s hard not to resent the idea of Hollywood, the idea of the movies as standing apart from and above the city.”

The nonfiction work is the centerpiece of the two-week IFC Center series “Movietown: Los Angeles Plays Itself and Other LA Visions,” consisting of two dozen films in which LA plays a major role — and are included in Andersen’s nearly three-hour video essay and love letter. The wide-ranging festival features noir classics, satires, futuristic thrillers, low-budget indies, and teen rom-coms, from Roman Polanski’s Chinatown, Todd Haynes’s Safe, Martha Coolidge’s Valley Girl, and Billy Woodberry’s Bless Their Little Hearts to James Cameron’s The Terminator, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point, John Singleton’s Boyz N the Hood, and Alex Cox’s Repo Man in addition to films by John Cassavetes, John McTiernan, Ridley Scott, Amy Heckerling, and Peter Bogdanovich.

Maybe there’s more to LA than what Alvy Singer argues in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall: “I don’t want to live in a city where the only cultural advantage is that you can make a right turn on a red light.”

Below are select highlights from this fourteen-day cinematic sojourn to the West Coast.

THE BIG LEBOWSKI (Joel & Ethan Coen, 1998)

Friday, July 15, 11:45 pm

Saturday, July 23, 11:40 pm

www.ifccenter.com/films/the-big-lebowski

One of the ultimate cult classics and the best bowling movie ever, the Coen brothers’ The Big Lebowski has built up such a following since its 1998 release that fans gather every year for Lebowski Fest, where they honor all things Dude, and with good reason. The Big Lebowski is an intricately weaved gem that is made up of set pieces that come together in magically insane ways. Jeff Bridges is awesome as the Dude, a laid-back cool cat who gets sucked into a noirish plot of jealousy, murder, money, mistaken identity, and messy carpets. Julianne Moore is excellent as free spirit Maude, Tara Reid struts her stuff as Bunny, and Peter Stormare, Flea, and Torsten Voges are a riot as a trio of nihilists. Also on hand are Philip Seymour Hoffman, David Huddleston, Aimee Mann, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, David Thewlis, Sam Elliott, Ben Gazzara, Jon Polito, and other crazy characters, but the film really belongs to the Dude and his fellow bowlers Jesus Quintana (John Turturro, who is so dirty he is completely cut out of the television version), Donny (Steve Buscemi), and Walter (John Goodman), who refuses to roll on Shabbos. And through it all, one thing always holds true: The Dude abides.

THE LONG GOODBYE (Robert Altman, 1973)

Friday, July 15, 5:30

Saturday, July 16, 1:20 & 10:00

www.ifccenter.com/films/the-long-goodbye

This is one odd detective story. King of the ’70s Elliott Gould stars as a mumbling Philip Marlowe who reluctantly becomes enmeshed in a murder case involving a friend of his played by former Yankee Jim Bouton. Marlowe lives next door to a harem of naked brownie-loving women, and he spends most of his time worrying about his cat. In fact, the opening fifteen minutes, in which he has to go out in the middle of the night to get cat food and then trick his cat, is absolutely priceless, one of the best cat story lines ever. The detective stuff plays second fiddle to director Robert Altman’s ’70s mood piece, which is fun to watch even at its most baffling and senseless.

Rowdy Roddy Piper tries to save the planet from an alien conspiracy in John Carpenter’s They Live

THEY LIVE (John Carpenter, 1988)

Saturday, July 16, 11:45 pm

Friday, July 22, 11:50 pm

www.ifccenter.com/films/they-live

How can you possibly not love a movie in which wrestling legend Rowdy Roddy Piper, brandishing a shotgun and standing next to an American flag, declares, “I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass . . . and I’m all out of bubblegum.” In John Carpenter’s tongue-in-cheek Reagan-era cult favorite, the goofy 1988 political sci-fi thriller They Live, Piper, who passed away in 2015 at the age of sixty-one, stars as John Nada, a drifter who arrives in L.A. and gets a job working construction, where he is befriended by Frank Armitage (Keith David), who is otherwise trying to keep to himself and away from trouble as he makes money to send back to his family. Frank invites John to stay at a tent city for homeless people, across the street from a church where John soon finds some disturbing things happening involving a blind preacher (Raymond St. Jacques), a well-groomed man named Gilbert (Peter Jason), and a bearded weirdo (John Lawrence) taking over television broadcasts and making dire predictions about the future. John then discovers that by using a pair of special sunglasses, he can see, in black-and-white, what is really going on beneath the surface: Alien life-forms disguised as humans have infiltrated Los Angeles, gaining positions of power and placing subliminal messages in signs and billboards, spreading such words and phrases as Obey, Consume, Submit, Conform, Buy, Stay Asleep, and No Independent Thought. John seeks help from Frank and cable channel employee Holly Thompson (Meg Foster), determined to reveal the hidden conspiracy and save the planet.

Aliens use television and billboards to send subliminal messages to humanity in prescient sci-fi satire

Loosely based on Ray Nelson’s 1963 short story and 1986 comic-book adaptation “Eight O’Clock in the Morning,” They Live is a fun, if seriously flawed, film that takes on Reaganomics, consumerism, the media, and capitalism and doesn’t much care about its huge, gaping plot holes. Carpenter, an iconoclastic independent auteur who had previously made such other paranoid thrillers as Assault on Precinct 13, Halloween, Escape from New York, and a remake of The Thing, wrote They Live under the pseudonym Frank Armitage (the name of David’s character as well as a reference to H. P. Lovecraft’s Henry Armitage from “The Dunwich Horror”) and composed the ultracool synth score with Alan Howarth. The movie is famous not only for Piper’s not exactly brilliant performance but for one of the longest fight scenes ever, as John and Frank go at each other for five and a half nearly interminable minutes, as well as the influence They Live had on activist artist Shepard Fairey, who admitted in 2003 that it “was a major source of inspiration and the basis for my use of the word ‘obey.’” The film is all over the place, a jumble of political commentary and B-movie nonsense, but it’s also eerily prescient, especially with what is going on in America today. Keep a watch out for such recognizable character actors as Sy Richardson, George Buck Flower, Susan Blanchard, Norman Alden, Lucille Meredith, and Robert Grasmere, whose names you don’t know but whose faces are oh-so-familiar.

Billy Wilder takes audiences down quite a Hollywood road in Sunset Boulevard

SUNSET BOULEVARD (Billy Wilder, 1950)

Sunday, July 17, 10:40 am & 3:40 pm

Tuesday, July 19, 11:15 am & 5:20 pm

www.ifccenter.com/films/sunset-boulevard

“You’re Norma Desmond. You used to be in silent pictures. You used to be big,” handsome young screenwriter Joe Gillis (William Holden) remarks to an older woman in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard. “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small,” the former star (Gloria Swanson) famously replies. It doesn’t get much bigger than Sunset Boulevard, one of the grandest Hollywood movies ever made about Hollywood. The wickedly entertaining film noir begins in a swimming pool, where Gillis is a floating corpse, seen from below. He then posthumously narrates through flashback precisely what landed him there. On the run from a couple of guys trying to repossess his car, the broke Gillis ends up at a seemingly abandoned mansion, only to find out that it is home to Desmond and her dedicated servant, Max Von Mayerling (Erich von Stroheim). They initially mistake Gillis for the undertaker who is coming to perform a funeral service and burial for Desmond’s pet monkey. (You’ve got to see it to believe it.) When Desmond discovers that Gillis is in fact a screenwriter, she lures him into working with her on her script for a new version of Salome, in which she is determined to play the lead role. “I didn’t know you were planning a comeback,” Gillis says. “I hate that word,” Desmond responds. “It’s a return, a return to the millions of people who have never forgiven me for deserting the screen.” But just as Desmond was unable to make the transition from silent black-and-white films to color and sound pictures, getting Salome off the ground is not going to be as easy as she thinks. Hollywood can be a rather vicious place, after all.

Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) keeps a close hold on screenwriter Joe Gillis (William Holden) in Sunset Boulevard

Nominated for eleven Oscars and winner of three — for the sharp writing, the detailed art/set decoration, and Franz Waxman’s score, which goes from jazzy noir to melodrama — Sunset Boulevard wonderfully bites the hand that feeds it, skewering Hollywood while making references to such real stars as Rudolph Valentino, Mabel Normand, John Gilbert, Greta Garbo, Wallace Reid, and Tyrone Power and such films as Gone with the Wind and King Kong. Actual publicity stills and movie posters abound, in Paramount offices and Desmond’s spectacularly designed home, which was once owned by J. Paul Getty and would later be used for Rebel without a Cause. Cecil B. DeMille, who directed Swanson in many silent films, plays himself in the movie, seen on set making Samson and Delilah. Desmond’s fellow bridge players are portrayed by silent stars Buster Keaton, H. B. Warner, and Anna Q. Nilsson. Meanwhile, before Swanson fired him, von Stroheim directed her in the silent film Queen Kelly, which is the movie Max shows Gillis in Desmond’s screening room. (Swanson herself would go on to make only three more feature films; she passed away in 1983 at the age of eighty-four.) John F. Seitz’s black-and-white cinematography and inventive use of camera placement, from underwater to high above the action, makes the most of Hans Dreier’s sets and Swanson’s fabulous costumes and makeup. Sunset Boulevard is the thirteenth and final collaboration between writer-director Wilder and writer-producer Charles Brackett, who together previously made The Lost Weekend and A Foreign Affair. Wilder and Holden would go on to make Stalag 17, Sabrina, and Fedora together. Finally, of course, Sunset Boulevard concludes with one of the greatest quotes in Hollywood history.

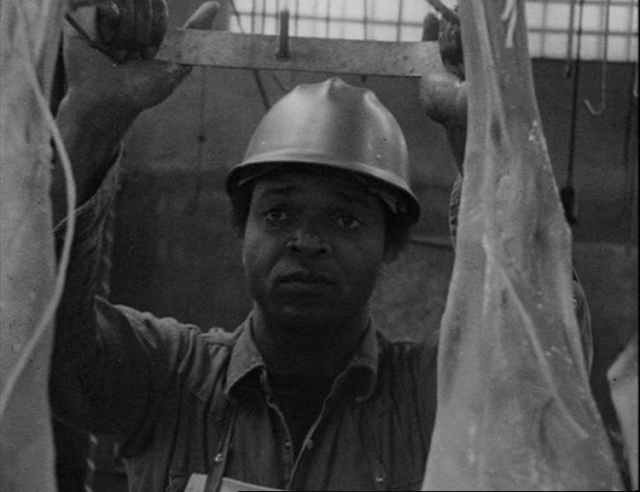

Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep examines black life in postwar America

KILLER OF SHEEP (Charles Burnett, 1977)

Wednesday, July 20, 2:30 & 7:00

Tuesday, July 26, 4:05

www.ifccenter.com/films/killer-of-sheep

www.killerofsheep.com

In 2007, Milestone Films restored and released Charles Burnett’s low-budget feature-length debut, Killer of Sheep, with the original soundtrack intact; the film had not been available on VHS or DVD for decades because of music rights problems that were finally cleared. (The soundtrack includes such seminal black artists as Etta James, Dinah Washington, Little Walter, and Paul Robeson.) Shot on weekends for less than $10,000, Killer of Sheep took four years to put together and another four years to get noticed, when it won the FIPRESCI Prize at the 1981 Berlin Film Festival. Reminiscent of the work of Jean Renoir and the Italian neo-Realists, the film tells a simple story about a family just trying to get by, struggling to survive in their tough Watts neighborhood in the mid-1970s.

The slice-of-life scenes are sometimes very funny, sometimes scary, but always poignant, as Stan (Henry Gayle Sanders) trudges to his dirty job in a slaughterhouse in order to provide for his wife (Kaycee Moore) and children (Jack Drummond and Angela Burnett). Every day he is faced with new choices, from participating in a murder to buying a used car engine, but he takes it all in stride. The motley cast of characters, including Charles Bracy and Eugene Cherry, is primarily made up of nonprofessional actors with a limited range of talent, but that is all part of what makes it all feel so real. Killer of Sheep was added to the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 1989, the second year of the program, making it among the first fifty to be selected, in the same group as Rebel Without a Cause, The Godfather, Duck Soup, All About Eve, and It’s a Wonderful Life, which certainly puts its place in history in context.

DOUBLE INDEMNITY (Billy Wilder, 1944)

Saturday, July 23, 11:15 am

Tuesday, July 26, 11:15 am & 6:15 pm

www.ifccenter.com

IFC Center is offering three chances to catch Billy Wilder’s endlessly romantic noir classic Double Indemnity. Three years after a brunette Barbara Stanwyck tried to swindle Henry Fonda in Preston Sturges’s The Lady Eve, a blonde Stanwyck is looking for a way out of her loveless marriage when opportunity knocks in the form of acerbic insurance salesman Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray). Stanwyck plays alluring, tough-talking femme fatale Phyllis Dietrichson, who falls for Neff and soon convinces him that they should do away with her husband (Tom Powers). They’re both in it “straight down the line,” as she repeats throughout the film, but insurance fraud investigator Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson) isn’t so sure that Mr. Dietrichson’s death was an accident.

John F. Seitz’s inventive black-and-white cinematography — watch for those Venetian blind shadows — set the standard for the genre. MacMurray, who had to be convinced by Wilder to take the part because he thought he’d be awful in the role, is sensational as Neff, oh-so-cool as he recites his cynical dialogue and lights matches with one hand. He might think he’s tough, but he’s no match for Stanwyck, who rules the roost. Both Stanwyck and MacMurray would go on to successful careers in television in the 1960s, he in My Three Sons, she in The Big Valley. Directed by Wilder from a script he wrote with Raymond Chandler based on a pulp novel by James Cain, with music by Miklós Rózsa — how’s that for a pedigree? — Double Indemnity was nominated for seven Oscars and won none.

THE EXILES (Kent Mackenzie, 1961)

Monday, July 25, 11:30 am

www.ifccenter.com/films/the-exiles

Founded in 1990 by Dennis Doros and Amy Heller as a way to preserve great orphaned works, Milestone Films first restored Charles Burnett’s wonderful Killer of Sheep and My Brother’s Wedding. Milestone, the UCLA Film & Television Archive, and preservationist Ross Lipman teamed up again to bring back Kent Mackenzie’s black-and-white slice-of-life tale The Exiles, which debuted at the 1961 Venice Film Festival and screened at the inaugural 1964 New York Film Festival before disappearing until its restoration, upon which it was selected for the 2008 Berlin International Film Festival. The Exiles follows a group of American Indians as they hang out on a long Friday night of partying and soul searching in the Bunker Hill section of Los Angeles, centering on Homer (Homer Nish) and Yvonne (Yvonne Williams), who are going to have a baby. After Yvonne makes dinner for Homer and his friends, the men drop her off at the movies by herself while they go out drinking and gambling and, in Tommy’s (Tommy Reynolds) case, looking for some female accompaniment.

As the night goes on, Homer, Yvonne, and Tommy share their thoughts and dreams in voice-over monologues that came out of interviews Mackenzie conducted with them. In fact, the cast worked with the director in shaping the story and getting the details right, ensuring its authenticity and realism, giving The Exiles a cinéma vérité feel. Although the film suffers from a poorly synced soundtrack — it is too often too clear that the dialogue was dubbed in later and doesn’t match the movement of the actors’ mouths — it is still an engaging, important independent work (the initial budget was $539) about a subject rarely depicted onscreen with such honesty. Mackenzie, who followed up The Exiles with the documentaries The Teenage Revolution (1965) and Saturday Morning (1971) before his death in 1980 at the age of fifty, avoids sociopolitical remonstrations in favor of a sweet innocence behind which lies the difficulties of the plight of American Indians assimilating into U.S. society.