Justice (Deirdre O’Connell), Christopher (Will Dagger), and Ginny (Jamie Brewer) watch Mariah Carey in Glitter in Corsicana (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

CORSICANA

Playwrights Horizons, Mainstage Theater

416 West 42nd St. between Ninth & Tenth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through July 17, $35-$99

www.playwrightshorizons.org

In her acceptance speech for winning the Tony for Best Actress for her performance in Dana H., Deirdre O’Connell said, “I would love this little prize to be a token for every person who is wondering, ‘Should I be trying to make something that could work on Broadway or that could win me a Tony Award? Or should I be making the weird art that is haunting me, that frightens me, that I don’t know how to make, that I don’t know if anyone in the whole world will understand?’ Please let me standing here be a little sign to you from the universe to make the weird art.”

O’Connell has followed up Dana H., in which she never speaks but instead remarkably conveys a prerecorded true story told by playwright Lucas Hnath’s mother, with Will Arbery’s Corsicana, which has its fair share of weird, starting with the word itself, which is spoken two dozen times by the four characters, each of whom lives in their own reality.

Corsicana takes place in the Texas town named after the island of Corsica. Thirty-three-year-old Christopher (Will Dagger) is a teacher and an aspiring filmmaker who lives with his thirty-four-year-old half sister, Ginny (Jamie Brewer), in the family’s ranch house. They are often visited by the sixtysomething Justice (Deirdre O’Connell), who was best friends with their recently deceased mother.

After her mom’s death, Ginny, who has Down syndrome, is looking for something new to do. She doesn’t want to go back to her job at the nursing home or rejoin the choir because she feels she doesn’t belong. “I’m worried. I can’t find my heart,” she tells her brother.

Ginny had suggested that Ginny meet her friend Lot (Harold Surratt), a sixtysomething reclusive artist and musician who has just been “discovered” via a magazine article; Christopher thinks it might be good for Ginny to write a song with Lot, who previously played an original song for Christopher called “Weird.” (The original music is by singer-songwriter and visual artist Joanna Sternberg.)

A self-taught outsider artist, Lot is a loner who has trouble communicating directly with others, speaking in a sharp, straightforward manner, using few words and prone to non sequiturs; he has no phone or computer. He doesn’t want to interact with either the virtual or real world. And although he believes he may be neurodivergent, he is not about to be a babysitter for a woman with special needs.

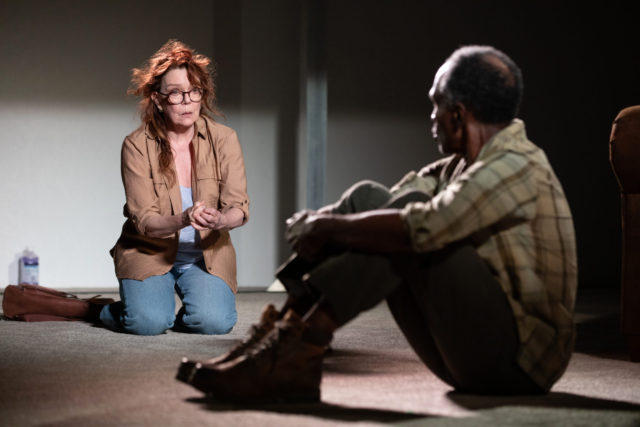

Justice (Deirdre O’Connell) pleads with Lot (Harold Surratt) in new Will Arbery play (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

He tells Christopher: “Yeah, I know ‘special needs.’ Why’d you come here? I know the place in the high school. The hallway in the high school. You know I’m not one of them, right?” Christopher replies, “What?” Lot: “I’m not special needs.” Christopher: “Oh — I didn’t think you were. I assumed the opposite.” Lot: “What’s the opposite? I was only a couple years in that hallway. And they knew I didn’t belong. Got a graduate degree in my forties. So don’t worry about me.” Christopher: “Oh, cool. In what?” Lot: “Experimental mathematics. I proved the existence of God.” Christopher: “Are you serious? Can I see?” Lot: “I threw it away. Art’s a better delivery system.”

Art may be a better delivery system, but Lot prefers not to show anyone his work or exhibit in a gallery, or to even sell it. When Justice, who believes she is being trailed by a ghost, asks to see his latest sculpture, he declares, “No, it’s not ready! You’re not allowed to look back there.” The audience is not allowed to look either; none of Lot’s work is ever revealed. He later compares capitalism and consumption as a “prison . . . a man-made evil.” He also claims that they are all surrounded by dinosaur ghosts.

As the characters continue to interact with one another, Lot is fearful about becoming part of something. “You trying to get me to believe in community?” he asks Justice, who replies, “No. I have no agenda.” Lot: “Uh-huh.” Justice: “What do you have against community?” Lot: “I don’t have to have all the same opinions as you,” as if choosing to spend time with people is an opinion.

But he does find common ground with Ginny, explaining that the two of them are “so complicated, people don’t want to think about it. So they make us more simple. In their brains. They don’t think about it, and they call us simple. And everything is about our needs. All our little needs. Our special needs. Everyone around us becoming burdened by our constant need. And if there’s something that we want? Well, it’s for them to decide if we really need it.”

Over the course of the play, all the characters find some form of commonality with the others while also maintaining barriers, particularly when it comes to physical contact of any kind. “People have to understand touch, and ask for permission, and respect boundaries,” Ginny tells Lot. “Touch can cause problems.”

Obie- and Tony-winning director Sam Gold, who has helmed such marvelously inventive productions as Fun Home, John, and A Doll’s House, Part 2 in addition to critically lambasted versions of King Lear, Hamlet, and Macbeth, injects Corsicana with, well, a weird edge throughout. Laura Jellinek and Cate McCrea’s stage consists of a pair of rotating brown couches set against a white backdrop and ceiling, but Justice and Lot spend time sitting on the floor. Often, when two characters are interacting, one or both of the other actors watch from the far corners. Several times, two of the actors push poles to move part of the set toward the audience in order to change Isabella Byrd’s canopy lighting. Meanwhile, the long, horizontal, slanted back white wall serves as the entrance to Lot’s studio, which he often locks to keep people out of his space — and head.

Christopher (Will Dagger) and Ginny (Jamie Brewer) seek connections in Corsicana (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

There is a lot of repetition in the play, which could use a significant amount of trimming from its two-and-a-half-hour length (including intermission). The terrific cast is led by Surratt’s (Familiar, Serious Money) powerful performance as the antisocial Lot — evoking the biblical figure who lived in Sodom, “a righteous man who was tormented in his soul by the wickedness he saw and heard day after day” — primarily standing stiffly upright when talking as he, Justice, Christopher, and Ginny form a kind of found family. Arbery (Pulitzer finalist Heroes of the Fourth Turning, Plano), who is from Texas and Wyoming, based Christopher and Ginny on himself and one of his seven sisters, who has Down syndrome. He also knows about unique families, having served as executive consultant on the third season of Succession.

Brewer (American Horror Story, Amy and the Orphans) brings an unfettered honesty to Ginny, Dagger (Among the Dead, The Antelope Party) is appropriately offbeat as Christopher, and O’Connell (Circle Mirror Transformation, In the Wake) is just the right kind of quirky as the, um, weird Justice, who is writing a book that echoes the subject of Arbery’s play. She explains to Christopher:

“Well, it’s about anarchism and gifts. About the belief that humans are fundamentally generous, or at least cooperative. That in our hearts, most of us really do want the good. It’s about the evils of centralized power, specially in a country as massive as the USA, let alone a state as big as Texas. It’s about an unforgiving land. It’s about unrealized utopias. It’s about how failing is the point. It’s about surrender. It’s about small groups. It’s about community. It’s about the right to well-being. It’s about family. It’s about the dead. It’s about ghosts. It’s about gentle chaos. It’s about contracts of the heart. And the belief that when a part of the self is given away, is surrendered to the needs of a particular time, in a particular place, then community forms. From the ghosts of the parts of ourselves we’ve given away. A new particular body. Born of our own ghosts. I don’t know. It’s about Texas.”

And there’s nothing weird about that. (Is there?)