John Cale and Lou Reed reunite to honor Andy Warhol in Songs for ’Drella

SONGS FOR ’DRELLA (Ed Lachman, 1990)

New York Film Festival, Lincoln Center

Francesca Beale Theater, Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center

144 West 65th St. between Broadway & Amsterdam Ave.

Tuesday, October 5, 4:30

www.filmlinc.org

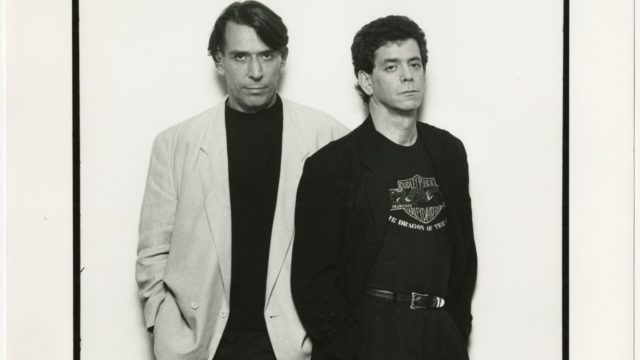

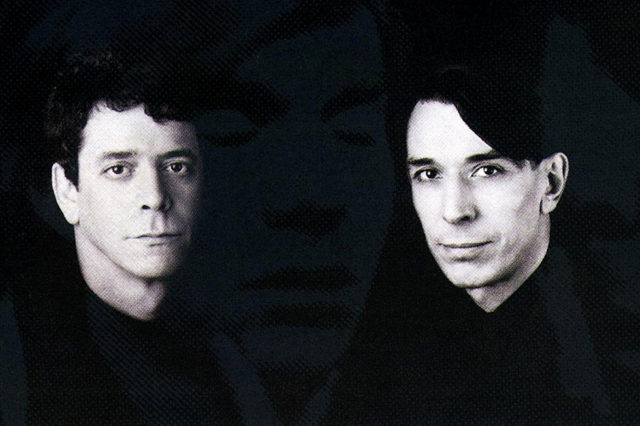

In December 1989, Velvet Underground cofounders John Cale and Lou Reed took the stage at BAM’s Howard Gilman Opera House and performed a song cycle in honor of Andy Warhol, who had played a pivotal role in the group’s success. The Pittsburgh-born Pop artist had died in February 1987 at the age of fifty-eight; although Cale and Reed had had a long falling-out, they reunited at Warhol’s funeral at the suggestion of artist Julian Schnabel. Commissioned by BAM and St. Ann’s, Songs for ’Drella — named after one of Warhol’s nicknames, a combination of Dracula and Cinderella — was released as a concert film and recorded for an album. The work is filled with factual details and anecdotes of Warhol’s life and career, from his relationship with his mother to his years at the Factory, from his 1967 shooting at the hands of Valerie Solanis to his dedication to his craft.

Directed, photographed, and produced by Ed Lachman, the two-time Oscar-nominated cinematographer of such films as Desperately Seeking Susan, Mississippi Masala, Far from Heaven, and Carol — Lachman also supervised the 4K restoration being shown at the New York Film Festival this week — Songs for ’Drella is an intimate portrait not only of Warhol but of Cale and Reed, who sit across from each other onstage, Cale on the left, playing keyboards and violin, Reed on the right on guitars. There is no between-song patter or introductions; they just play the music as Robert Wierzel’s lighting shifts from black-and-white to splashes of blue and red. Photos of Warhol and some of his works (Electric Chair, Mona Lisa, Gun) are occasionally projected onto a screen on the back wall.

“When you’re growing up in a small town / Bad skin, bad eyes — gay and fatty / People look at you funny / When you’re in a small town / My father worked in construction / It’s not something for which I’m suited / Oh — what is something for which you are suited? / Getting out of here,” Reed sings on the opener, “Smalltown.” Cale and Reed share an infectious smile before “Style It Takes,” in which Cale sings, “I’ve got a Brillo box and I say it’s art / It’s the same one you can buy at any supermarket / ’Cause I’ve got the style it takes / And you’ve got the people it takes / This is a rock group called the Velvet Underground / I show movies of them / Do you like their sound / ’Cause they have a style that grates and I have art to make.”

Songs for ’Drella is screening at NYFF59 in new 4K restoration

Cale and Reed reflect more on their association with Warhol in “A Dream.” Cale sings as Warhol, “And seeing John made me think of the Velvets / And I had been thinking about them / when I was on St. Marks Place / going to that new gallery those sweet new kids have opened / But they thought I was old / And then I saw the old DOM / the old club where we did our first shows / It was so great / And I don’t understand about that Velvets first album / I mean, I did the cover / and I was the producer / and I always see it repackaged / and I’ve never gotten a penny from it / How could that be / I should call Henry / But it was good seeing John / I did a cover for him / but I did it in black and white and he changed it to color / It would have been worth more if he’d left it my way / But you can never tell anybody anything / I’ve learned that.”

The song later turns the focus on Reed, recalling, “And then I saw Lou / I’m so mad at him / Lou Reed got married and didn’t invite me / I mean, is it because he thought I’d bring too many people? / I don’t get it / He could have at least called / I mean, he’s doing so great / Why doesn’t he call me? / I saw him at the MTV show / and he was one row away and he didn’t even say hello / I don’t get it / You know I hate Lou / I really do / He won’t even hire us for his videos / And I was so proud of him.”

Reed does say hello — and goodbye — on the closer, “Hello It’s Me.” With Cale on violin, Reed stands up with his guitar and fondly sings, “Oh well, now, Andy — I guess we’ve got to go / I wish some way somehow you like this little show / I know it’s late in coming / But it’s the only way I know / Hello, it’s me / Goodnight, Andy / Goodbye, Andy.”

It’s a tender way to end a beautiful performance, but Lachman has added a special treat after the credits, with one final anecdote and the original trailer he made for Reed’s 1974 song cycle, Berlin. Songs for ’Drella is screening October 5 at 4:30 at the Francesca Beale Theater; it is also being shown October 2 prior to the free outdoor presentation of Todd Haynes’s new documentary, The Velvet Underground, in Damrosch Park, which will be followed by a Q&A with Lachman and Haynes. Lachman and Haynes will also be part of a Q&A with producers Christine Vachon and Julie Goldman and editors Affonso Gonçalves and Adam Kurnitz at the September 30 screening of The Velvet Underground at Alice Tully Hall; Cale was supposed to attend but has had to cancel.

Todd Haynes documents the history of the Velvet Underground in new film

THE VELVET UNDERGROUND (Todd Haynes, 2021)

Thursday, September 30, Alice Tully Hall, 6:00

Saturday, October 2, Damrosch Park, 7:00

Film Comment Live: The Velvet Underground & the New York Avant-Garde, Sunday, October 3, Damrosch Park, free, 4:00

www.filmlinc.org

Much of Haynes’s documentary, which will have its theatrical premiere October 14–21 at the Walter Reade (and streaming on Apple+ beginning October 15), focuses on Warhol’s position in helping develop and promote the Velvets. “Andy was extraordinary, and I honestly don’t think these things could have occurred without Andy,” Reed, who died in 2013, says. “I don’t know if we would have gotten the contract if he hadn’t said he’d do the cover or if Nico wasn’t so beautiful.”

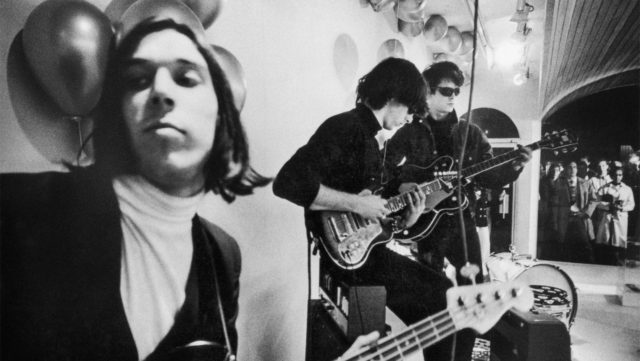

Haynes details the history of the group by delving into Cale and Reed’s initial meeting, the formation of the Primitives with conceptual artists Tony Conrad and Walter DeMaria, and the transformation into the seminal VU lineup at the Factory under Warhol’s guidance — singer-songwriter-guitarist Reed, Welsh experimental composer and multi-instrumentalist Cale, guitarist Sterling Morrison, drummer Maureen Tucker, and German vocalist Nico.

Haynes and editors Gonçalves and Kurnitz pace the film like VU’s songs and overall career, as they cut between new and old interviews and dazzling archival photographs and video, frantic and chaotic at first, then slowing down as things change drastically for the band They employ split screens, usually two but up to twelve boxes at a time, to deluge the viewer with a barrage of sound and image. Among the talking heads in the film are composer and Dream Syndicate founder La Monte Young, actress and film critic Amy Taubin, actress and author Mary Woronov, Reed’s sister Merrill Reed-Weiner, early Reed bandmates and school friends Allan Hyman and Richard Mishkin, filmmaker and author John Waters, manager and publicist Danny Fields, composer and philosopher Henry Flynt, and avant-garde filmmaker and poet Jonas Mekas. “We are not part really of the subculture or counterculture. We are the culture!” Mekas, who passed away in 2019 at the age of ninety-six, declares.

Haynes, who has made such previous music-related films as Velvet Goldmine, set in the 1970s glam-rock era, and I’m Not There, a fictionalized musical inspired by the life and career of Bob Dylan, also speaks extensively with Cale and Tucker, who hold nothing back, in addition to Sterling Morrison’s widow, Martha Morrison; singer-songwriter Jackson Browne, who opened up for the Velvets; and big-time fan Jonathan Richman (of Modern Lovers fame). While everyone shares their thoughts about Warhol, the Factory, the Exploding Plastic Inevitable shows, and the eventual dissolution of the band, Haynes bombards us with clips from Warhol’s Sleep, Kiss, Empire, and Screen Tests (many opposite the people who appear in the film) as well as works by such artists as Maya Deren, Jack Smith, Kenneth Anger, Barbara Rubin, Tony Oursler, Stan Brakhage, and Mekas and paintings by Warhol, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Mark Rothko. It’s a dizzying array that aligns with such VU classics as “I’ll Be Your Mirror,” “I’m Waiting for the Man,” “Heroin,” “White Light / White Heat,” “Sister Ray,” “Pale Blue Eyes,” and “Sweet Jane.”

Several speakers disparage the Flower Power era, Bill Graham, and Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, with Tucker admitting, “This love-peace crap, we hated that. Get real.” They’re also honest about the group’s own success, or lack thereof. Tucker remembers at their first shows, “We used to joke around and say, ‘Well, how many people left?’ ‘About half.’ ‘Oh, we must have been good tonight.’” And there is no love lost for Reed, who was not the warmest and most considerate of colleagues.

The Velvets continue to have a remarkable influence on music and art today despite having recorded only two albums with Cale (The Velvet Underground and Nico and White Light / White Heat) and two with Doug Yule replacing Cale (The Velvet Underground and Loaded) in a span of only three years. Haynes (Far from Heaven, Safe) sucks us right into their extraordinary world and keeps us swirling in it for two glorious hours of music, gossip, art, celebrity, and backstabbing. If you end up watching the film at home, turn it up loud. No, louder than that. Even louder. . . .