Bob Dylan’s Shadow Kingdom is available online through July 20 at midnight

Who: Bob Dylan

What: Prerecorded streaming concert film

Where: veeps

When: Available on demand through July 25 at 11:59 pm

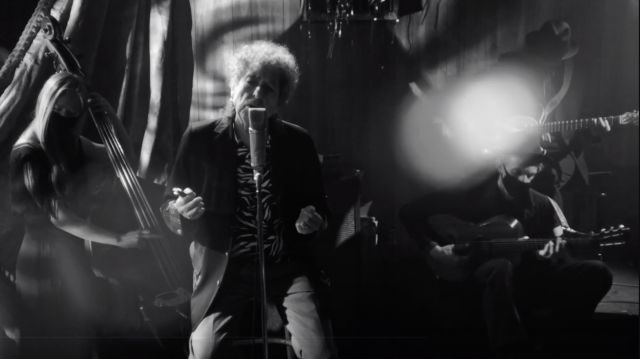

Why: “What was it you wanted / Tell me again so I’ll know / What’s happening in there / What’s going on in your show / What was it you wanted / Could you say it again / I’ll be back in a minute / You can tell me then,” Bob Dylan sings on “What Was It You Wanted,” one of thirteen tunes that make up his first-ever livestreamed performance, the fifty-minute prerecorded concert film Shadow Kingdom: The Early Songs of Bob Dylan, available on the online veeps platform through July 25 at 11:59 pm. There was much speculation and little information in advance as to what the stream would be, although a brief trailer gave a hint of what to expect, a clip of Dylan playing a rollicking blues version of 1971’s “Watching the River Flow” in a smoky speakeasy, filmed in black-and-white.

For decades of the Never Ending Tour, fans have learned to have no expectations when seeing Bob live; he’ll play whatever he wants, continually reinventing tracks from his extensive catalog in fascinating ways, often almost to the point of unrecognizability, but that’s all part of the excitement. The veeps chat lit up with naysayers, complaining that the show was not actually live, with a handful arguing that Dylan wasn’t even really singing, that he and his band — who were wearing masks even though the crowd, which included a number of smokers in the small, claustrophobic space, was not — were lip syncing and miming with their instruments. Some of the grumblers demanded their money back, whereas other Dylanheads declared it was the best twenty-five bucks they’d spent since music venues were shuttered back in March 2020.

The closing credits say Bob was accompanied by Janie Cowen on upright bass, Joshua Crumbly on electric bass, Shahzad Ismaily on keyboards and accordion, and Buck Meek on guitar — many in the chat wondered where regular bassist Tony Garnier and guitarist Charlie Sexton were — but online hypotheses are making the case that not only are they not actually playing the music, but it was prerecorded by a different group of musicians. What’s the truth? We’re certainly not going to get it from Dylan, who filled his must-read memoir with falsehoods that we ate up despite knowing that.

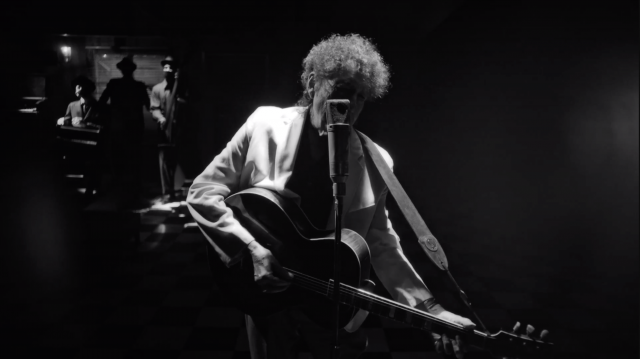

Some chatters were mad that the show was not in color; others were furious about the cigarettes, as if the smoke were coming through their screens; while others were more interested in the wedding ring Dylan was suddenly wearing. Far, far more fans were overjoyed to see Bob with a guitar in his hands — arthritis has prevented him from picking up a six-string for a bunch of years, concentrating instead on piano — and sounding better than he has in a long time, his voice clearly rested from a year and a half off the road. (But was he really singing or playing the guitar and harmonica?) The best way to experience the show is to forget about all that and just sit back and watch the music flow, like you were hanging out in Greenwich Village in the 1960s. (Unfortunately, the chat was only available during the initial stream, so when you watch it, you’ll have “to be alone with” Bob, not interacting with a rabid online audience.)

Dylan reached relatively deep into his past, pulling out new versions of such favorites as “When I Paint My Masterpiece” (masterful!), “Queen Jane Approximately” (majestic!), and “Forever Young” (eternal!) alongside such less-familiar cuts as “To Be Alone with You” from Nashville Skyline, “The Wicked Messenger” from John Wesley Harding, and “Pledging My Time” from Blonde on Blonde. Some of the tunes hadn’t been performed live in more than ten years; “What Was It You Wanted” last made a setlist in 1995.

Dylan began toying with the lyrics right from the opening number, as if adapting them to the pandemic, changing “Gotta hurry on back to my hotel room / Where I got me a date with a pretty little girl from Greece [also sung as “Botticelli’s niece”] / She promised she’d be right there with me / When I paint my masterpiece” to “Gotta hurry on back to my hotel room / Gonna wash my clothes, scrape off all of the weeds / Gonna lock the doors and turn my back on the world for a while / I’ll stay right there till I paint my masterpiece.” A few songs later, he changed “To be alone with you / Just you and me / Now won’t you tell me true / Ain’t that the way it oughta be? / To hold each other tight / The whole night through / Ev’rything is always right / When I’m alone with you” to “To be alone with you / Just you and I / Under the moon / ’Neath the star-spangled sky / I know you’re alive / And I am too / My one desire / Is to be alone with you.”

Bob Dylan is in great form in first online concert film, performing in a dark, smoky room

As at his live shows, the Bobster — who turned eighty this past May, when the film was shot in a fictional Santa Monica nightclub over a seven-day period (not, as mentioned in the credits, at the nonexistent Bon Bon Club in Marseille) — does not talk to the audience; he doesn’t introduce songs or include any concert patter. When I saw him at the Prospect Park Bandshell in 2008, the crowd nearly flipped out when he said he was glad to be back in Brooklyn, surprising us that he knew where he was. My only quibble with the stream is that the name of each song appears onscreen in big, bold letters before it is played; much of the fun at Dylan shows is trying to figure out what the next song is as it starts. I’ll never forget my best friend asking me at a 1978 concert on the Street Legal tour, “When is he going to play ‘Tangled Up in Blue’?” I had to tell him that Bob had just played it.

Each song in Shadow Kingdom is its own set piece, with Dylan in a different position on the stage, wearing one of several outfits. Regardless of where he is sitting or standing, the old-fashioned microphone blocks most of his mouth, furthering the chat conspiracy theory that he is lip syncing. It also prevents us from getting a better view of his extraordinary vocal phrasing, a technique that for him only improves with age, whether on his originals or standards; Dylan can shape a word like nobody else. He never moves around much during songs, but he does show off a few teeny gestures in “Queen Jane Approximately” and “Most Likely You Go Your Way,” (barely) swaying his shoulders and legs (his feet appear to be nearly glued to the floor) while making fists, pointing, and raising his arms a bit. (That’s probably not part of Dom McDougal’s choreography.) The close-knit, intimate production design is by Hannah Hurley-Espinoza and Ariel Vida, with cinematography by Lol Crawley, whose camera remains still when it is on Dylan but does occasionally pan through the band and the crowd. (By the way, just who are those people who got into the show?)

Bob Dylan is as much of a mystery as ever in streaming, limited-run concert film

The name of the show might have come from Robert E. Howard’s 1929 short story, “The Shadow Kingdom,” in which the Texas-born pulp fiction writer and Conan the Barbarian creator explains, “As he sat upon his throne in the Hall of Society and gazed upon the courtiers, the ladies, the lords, the statesmen, he seemed to see their faces as things of illusion, things unreal, existent only as shadows and mockeries of substance. Always he had seen their faces as masks, but before he had looked on them with contemptuous tolerance, thinking to see beneath the masks shallow, puny souls, avaricious, lustful, deceitful; now there was a grim undertone, a sinister meaning, a vague horror that lurked beneath the smooth masks. While he exchanged courtesies with some nobleman or councilor he seemed to see the smiling face fade like smoke and the frightful jaws of a serpent gaping there. How many of those he looked upon were horrid, inhuman monsters, plotting his death, beneath the smooth mesmeric illusion of a human face? Valusia — land of dreams and nightmares — a kingdom of the shadows, ruled by phantoms who glided back and forth behind the painted curtains, mocking the futile king who sat upon the throne — himself a shadow.” More clues from Dylan, perhaps, or yet another red herring? Does it matter?

Directed, produced, and edited by Alma Har’el, an Israeli American music video and film director who has worked with such bands as Beirut, Sigur Rós, and Balkan Beat Box and has made such films as Honey Boy, Bombay Beach, and LoveTrue, the presentation, too short at less than an hour, marvelously captures the mysterious enigma that is Robert Allen Zimmerman, the Minnesota-born folk-rock troubadour who has changed the planet with his music, reinventing himself umpteen times over his more than six-decade-long career. During the coronavirus crisis, he released the outstanding album Rough and Ready Ways, and he has now entered the streaming realm. What’s next? I certainly am not going to hold my breath waiting for a live Zoom concert or interactive Instagram talkback, but will there be a Shadow Kingdom: The Later Songs of Bob Dylan? Will the show ever be available again, on CD, LP, DVD, Spotify, etc.? Will the Never Ending Tour reemerge, after having not been seen since December 8, 2019? It’s Dylan, so it’s best not to expect anything — except something strange, something unusual, something wonderful. Whichever way he is likely to go, we worshippers are sure to follow.