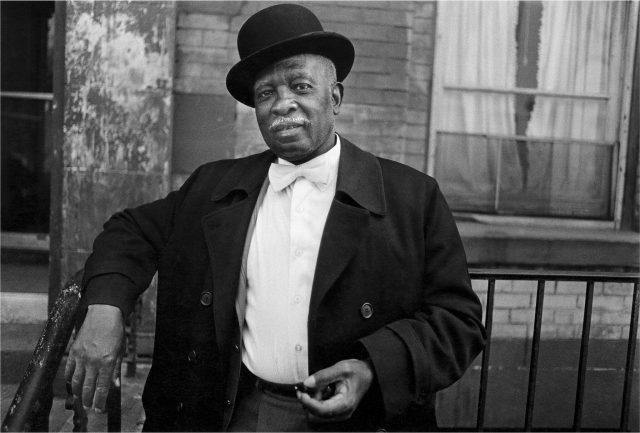

Dawoud Bey, A Man in a Bowler Hat, Harlem, NY, from “Harlem, U.S.A.,” gelatin silver print, ca. 1976 (collection of the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York; Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago; and Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco / © Dawoud Bey)

Who: Dawoud Bey, Torkwase Dyson, Elisabeth Sherman

What: Live online discussion

Where: Whitney Museum Zoom

When: Thursday, July 8, free with advance RSVP, 6:00 (exhibit continues through October 3)

Why: One of the many pleasures of “Dawoud Bey: An American Project,” the exemplary survey of the work of Queens-born photographer Dawoud Bey, is listening to him describe his process on the audio guide. The sixty-eight-year-old artist and Columbia College Chicago professor shares detailed aspects of his career while discussing numerous photos and series. You can hear more from Bey on July 8 at 6:00 when he participates in the Zoom talk “Narrative Materiality” with interdisciplinary artist Torkwase Dyson, moderated by exhibition cocurator Elisabeth Sherman.

On the audio guide, Bey talks about about his series “Night Coming Tenderly, Black,” a 2017 commission for the Front Triennial in Cleveland consisting of photos taken along what was the Underground Railroad in Ohio, dark shots of houses, trees, and the sea without people, “Of necessity, those locations, most of them were never known. They couldn’t be. They weren’t supposed to be. So there is that layer of invisibility built into the history. And so what I did was through research finding a few sites that are in fact known to be related to the Underground Railroad and then began to look at the landscape around those sites imagining a fugitive African American moving through that landscape, what that landscape might have looked like and felt like.”

In her catalog essay “Black Compositional Thought: Black Hauntology, Plantationscene, and Paradoxical Form,” Dyson writes, “Blackness will swallow the whole of terror to be free. It will move across distances, molecules, units — through atmospheres and concrete, in magic and bloodstreams to self-liberate. To image and imagine movements and geographies of freedom, known and unknown, is to regard this space as irreducible, or to regard black spatial geography as irreducible. ‘Night Coming Tenderly, Black’ is attuned to the irreducible place of black liberation inside terror. Each photograph makes manifest in the viewer a full-body, ongoing refusal to belong to a nation, land, person, or state under a system of terror, as conditioned by architecture, agriculture, modernity, or industrialized white supremacy. The process of freeing a full black body from spatial terror while black flesh holds and is seen as material and terror is liberation.”

Bey continues, “They’re all about the imagination. Looking closely at a piece of the land and noticing all of these thorns that certainly make the landscape so much more threatening if one had to move through it. So when I thought about it through that particular narrative, the landscape became for me a very transformed space. And that’s the space and place that I want the viewer to think about when they look at that work. I want them to completely forget about the present. This work is not about the present, which is why those photographs are all so large. I wanted to create a physical space for the viewer to enter into that, allow them just to be in that landscape.”

Named after a quote from Langston Hughes’s poem “Dream Variation” — “Rest at pale evening. . . . / A tall, slim tree. . . . / Night coming tenderly / Black like me.” — the series is notable in that there are no people in these dark, mysterious photographs, which more than hint at the ghosts of those who escaped slavery through the Underground Railroad as well as their descendants. These large-scale works demand and reward intense viewing, beautiful in and of themselves while imbued with the narrative of this country’s original sin.

“Night Coming Tenderly, Black” is one of only several powerful series in the show, which continues on the first and eighth floors of the Whitney through October 3. Bey’s 2012 “Birmingham Project,” which was included in the New Museum’s recently closed “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” features black-and-white diptychs that pair a photo of a child the same age as one of the four Black girls (Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley) killed in the 1963 KKK bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Alabama and the two boys (Johnny Robinson, Virgil Ware) murdered in the aftermath with an image of a grown woman or man the age the victims would have been in 2012 had they lived. It’s a brutal reminder of what racism continues to take away, evoking the missing men, women, and children in “Night Coming Tenderly, Black.”

Bey’s first series, “Harlem, USA,” invites viewers into the Harlem of the mid- to late-1970s, with 35mm black-and-white photographs of Deas McNeil in his barbershop, two girls having fun posing in front of a local restaurant, three well-dressed women leaning on a “Police Line” barrier during a parade, and a dapper old man wearing a white bowtie and a black bowler.

In the 1980s, Bey headed upstate to Syracuse, where he again focused on the Black community in its natural surroundings. “It was a deliberate choice to foreground the Black subject in those photographs, giving them a place not only in my pictures . . . but on the wall[s] of galleries and museums when that work was exhibited,” Bey notes. He moved from the 35mm wide-angle-lens camera to a tripod-mounted 4 × 5-inch-format camera for his Polaroid street portraits of strangers he met, including a boy eating a Foxy Pop, a young man and woman hugging in Prospect Park, and a young man on an exercise bicycle in Amityville, all looking directly at the camera. Bey would give the instant Polaroid picture to his subjects, then print them later from the negative; for this exhibit, they can now be seen nearly life-size.

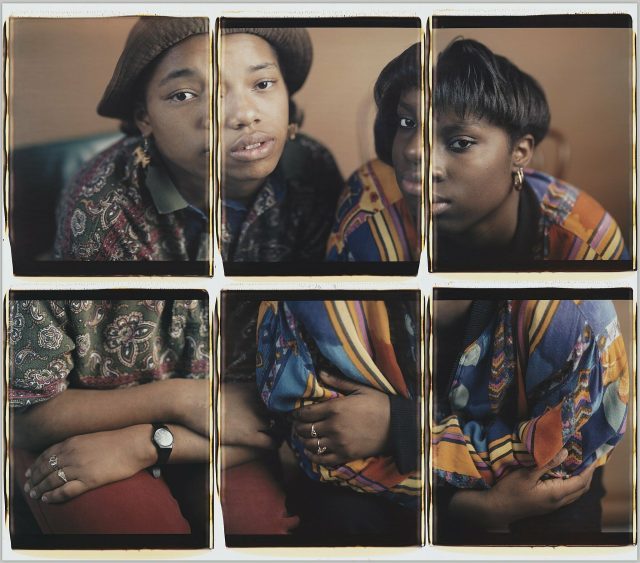

Dawoud Bey, Martina and Rhonda, Chicago, IL, six dye diffusion transfer prints (Polaroid), 1993 (Whitney Museum of American Art; gift of Eric Ceputis and David W. Williams 2018.82a-f / © Dawoud Bey)

In 1991, Bey turned to a two-hundred-pound, six-foot-tall, five-foot wide Polaroid camera to photograph friends and such fellow artists as Lorna Simpson, putting together two, three, and as many as six exposures for each, the edges of the Polaroids visible, letting us inside his process as he emphasizes the complexities of the people in these color images.

Another room is dedicated to Bey’s “Class Pictures,” color photos of marginalized teenagers whose words are seen alongside the pictures. “Sometimes I wonder what color my soul is. I hope that it’s the color of heaven,” Omar says. Kevin admits, “Thanks to the death of my father I grew up much too fast and never learned how to ask anyone for help. I carry my own burdens . . . alone. This is my curse.”

Bey returned to Harlem in 2014–17 for “Harlem Redux,” pigmented inkjet prints that focus on place rather than people in a changing neighborhood that is very different from the Harlem he photographed four decades earlier, best exemplified by Girls, Ornaments, and Vacant Lot, NY, which depicts two hair advertisements of smiling Black girls next to an abandoned, litter-strewn, fenced-in area. “One of the things that was beginning to happen in Harlem was that there were these, as I called them, spaces where something used to be,” Bey says on the audio guide. “And when those places are completely obliterated, when they’re torn down and you end up with a vacant lot, there’s a kind of disruption of place memory. Because at some point, even if you know the community well, you can’t quite remember what used to be there. And that to me was a profound experience.” A visit to the Whitney to see “Dawoud Bey: An American Project” is a profound experience itself, reminding us of what was, and projecting what might be.