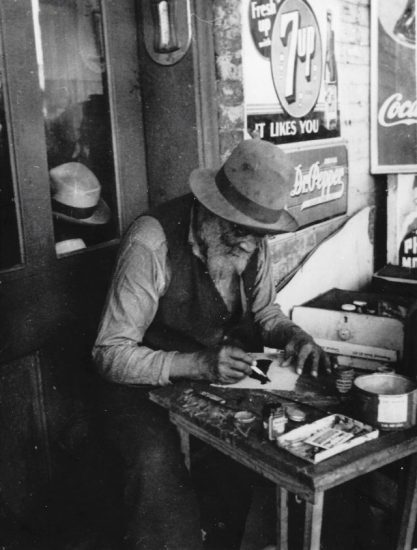

The life and art of Bill Traylor are the subject of illuminating documentary (photo courtesy Jean and George Lewis / Caroline Cargo Folk Art Collection)

BILL TRAYLOR: CHASING GHOSTS (Jeffrey Taylor, 2018)

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

Opened April 16

filmforum.org

www.billtraylorchasingghosts.com

“I think Traylor is probably the greatest artist you’ve never heard of, but he’s getting heard of more and more,” art critic Roberta Smith says at the beginning of Jeffrey Taylor’s Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts, an insightful documentary that runs April 16–22 at Film Forum — both virtually and in person at the West Houston St. theater.

I well remember the first time I truly encountered the scope of Bill Traylor’s art, at a pair of 2013 exhibits at the American Folk Art Museum. I had seen his work before, but these two shows opened my eyes to his immense self-taught skill and his poignant and personal view of the world he had experienced, becoming, in his later years, a unique chronicler of the American South, from slavery and the Civil War through the Great Migration and the Great Depression to Jim Crow and WWII. He passed away in 1949 at the age of ninety-six, leaving behind some 1,500 drawings, all made between 1939 and 1942; it would still be decades until he would be duly recognized him as one of the most important artists of the twentieth century.

Director, producer, and editor Taylor and writer-producer Fred Barron tell Traylor’s uniquely American tale through archival photos, commentary from art connoisseurs and historians, members of Traylor’s family, and, most important, images of hundreds of his works. Born into slavery in Benton, Alabama, in 1853, Traylor was a slave on a cotton plantation, a field hand, a tenant farmer, a shoe repairman, and an ill homeless man while fathering nine children with multiple women before spending three years sitting behind a small refrigerated soda case on Monroe St. in Montgomery, Alabama, drawing both from memory and observation of the bustling Black community in front of him. Using anything he could find — torn paper, stained cardboard with logos on one side — Traylor would draw flat, silhouetted objects, primarily in black but with flourishes of blue, red, and occasional yellows, imbued with a musicality that breathes life into them while also exploring race and class; today, his art evokes elements of both Jacob Lawrence and Kara Walker. Taylor often juxtaposes Traylor’s drawings with photographs of places that might have served as inspiration, which offer further understanding of the art and the man.

“There are certain elements in the work — the use of animal spirits and plant spirits, and there’s hybrid people, there’s were-people — that all of these speak to someone operating intentionally with the desire to render the fantastic. So he’s giving us a whole enchanted, magical realm,” writer, musician, and producer Greg Tate says, adding, “The mystery prevails throughout.” Artist Radcliffe Bailey notes, “When I look at Traylor’s work, I see this freedom of expressing, or seeing what’s going on around him but also being very lyrical about it.” Among the others celebrating Traylor with a deep reverence are archivist Dr. Howard O. Robinson II, professor Richard Powell, and curator Leslie Umberger. Taylor includes readings by actors Russell G. Jones and Sharon Washington, songs by Willie King, Lead Belly, Buddy Guy, and Chick Webb, and tap dances by Jason Samuels Smith, along with the words of Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes as well as the white painter and teacher Charles Shannon, who championed and represented Traylor.

The film’s latter section focuses on Traylor’s descendants, including his great-grandson Frank L. Harrison, who tears up when talking about his ancestor. Some knew of Traylor, and some didn’t, which is all part of his legacy. Umberger, who curated the major 2018-19 Smithsonian retrospective “Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor,” sums it up when she states, “He put down this entire oral history in the language that was available to him, which was the language of pictures.” What pictures they are, and we now know more about where they came from, thanks to Chasing Ghosts.