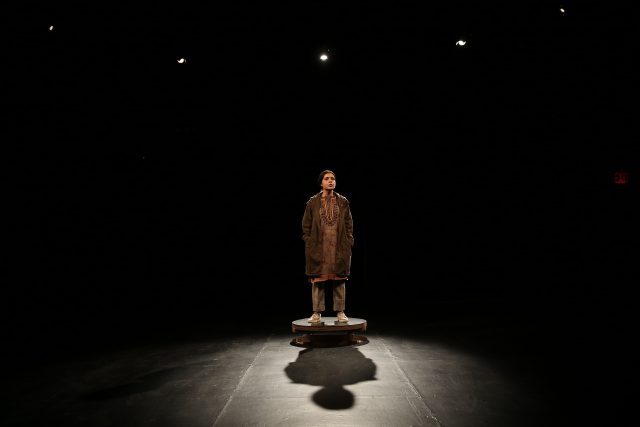

Nazira Hanna delivers the first of three monologues in Richard Maxwell’s Queens Row (photo © Paula Court)

The Kitchen

512 West 19th St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

Wednesday – Saturday through January 25, $20-$25

212-255-5793 ext11

thekitchen.org

www.nycplayers.org

Experimental theater master Richard Maxwell’s Queens Row is a poetic meditation on loneliness in a postapocalyptic world. Continuing at the Kitchen through January 25, the sixty-minute show takes place in the Chelsea institution’s empty upstairs gallery space, a black box with an exposed sink area and a small balcony. The play consists of three monologues delivered by a trio of nonprofessional actors, sharing their characters’ deeply personal stories surrounding a shooting death, each woman somewhat more physical and emotional than the one before. First up is a woman (mixed-media artist Nazira Hanna) in a Native American-style top who is from the fictional town of Queens Row, Massachusetts; she stands stock-still on a small circular platform carved right out of the floor and lifted slightly by blocks of wood. Her words are cold and direct, her body rigid, as she announces, “I am a woman who had a child. I don’t have a name. I don’t have ID, and I never did, if you can imagine. There is no record of my fingertips or my eyeballs. . . . I was born and no one could stop that from happening. I had a child, and no one could stop that from happening. My son was killed, and no one could stop that from happening. And I exist in this place, asserting a certain right to exist, and to speak, and just like you, hopelessly existing.” She talks of a civil war, of riots “fueled by racism, xenophobia, foreign influence, class anger, and a simmering paranoia, hysteria on all sides.” The play was inspired by a dystopian dream Maxwell had, and her tale is like a nightmare, tinged with reality.

Soraya Nabipour picks up the story of the impact of loss in NYC Players production at the Kitchen (photo © Paula Court)

When she is done, she walks offstage through a door and is replaced by a second, younger woman (theater maker, facilitator, and PhD researcher Soraya Nabipour) from Odessa, Texas, wearing sneakers, black leggings, and a red sweater. She addresses a person no longer with us, bringing up seemingly random incidents from their past. “I string together memories as though it were some kind of lifeline,” she says. “Is it that we’re so much the same or that we need each other. We horrify each other but we’d die without each other, you know this, and you can’t stand it. Love is the thing you do when there’s nothing left to do. Love is the thing to do beyond words.” She is slightly more active although still appears confined, her past haunting her.

She is followed by a third woman (musician Antonia Summer, who recently trained at the National Youth Theatre in London) in a colorful shirt and long hair. She is from Las Cruces, New Mexico, and moves her body in herky-jerky ways that match her awkward speech patterns; she speaks as if she is learning language right in front of us. “t 6 d 5 6 s 5 6 e r r t s…………………… ient to fine a ja e, msrtik talking to …. pl this is right mao i, r;lorm r p & u.p.i. I,” she says before becoming understandable. “I get electrified with excitement when the towers which dot the horizon light up and connect together aligning that curve that arcs into me blasting my insides with light I am the offspring orphaned by fate and fatality My.” She talks of a father and a mother, of pain and desire, and asks, “whut is progeny?”

Antonia Summer is the liveliest of three connected women in Richard Maxwell’s postapocalyptic Queens Row (photo © Paula Court)

Written and directed by Maxwell, who previously presented The Evening, Natural Hero, and The End of Reality at the Kitchen with his NYC Players company, Queens Row is a gripping fantasy of a frightening near-future. Each character is circled above by a dozen lights, casting dramatic, often eerie shadows across the floor. (The set and lighting design is by Sascha van Riel, with costumes by Kaye Voyce.) The show isn’t so much a warning shot as an alternate reality that hovers just outside our purview; Maxwell includes several ghostly moments that are as scary as they are disconcerting. Hanna, Nabipour, and Summer — perhaps not uncoincidentally brown, black, and white — are each effective in her own right, the three of them interrelated by absence, implying how we all are connected in this dangerous universe, where dire actions have far-reaching consequences. As always with NYC Players, it is a challenging experience, told in uniquely Maxwellian style.