Bryce Dessner’s Triptych (Eyes of One on Another) runs at BAM June 6-8 (photo by Richard Termine)

BAM Howard Gilman Opera House

Peter Jay Sharp Building

230 Lafayette Ave.

June 6-8, $30-$60, 7:30

718-636-4100

www.bam.org

I was prepared to be blown away by Bryce Dessner’s Triptych (Eyes of One on Another). I’m a big fan of his artsy rock group, the National; I love (who doesn’t?) Patti Smith, whose text figures prominently in the piece; and I thoroughly enjoyed the first part of the Guggenheim’s “Implicit Tensions: Mapplethorpe Now” exhibit, which includes several images that appear in Dessner’s seventy-minute multimedia work. Perhaps my expectations were too high.

Inspired by the 1990 obscenity case against Mapplethorpe’s “The Perfect Moment” exhibit, which took place in Dessner’s hometown of Cincinnati when he was a teenager, Triptych (Eyes of One on Another) explores demons and desire, objectification and beauty, specifically in Mapplethorpe’s XYZ portfolios, which focus on sadomasochism, flowers, and African American male nudes. Accompanying the large-scale projections (by Simon Harding), which appear on a front scrim and/or the back wall, is text from the trial and writings by Smith and poet and activist Essex Hemphill, the latter a critic of Mapplethorpe’s. Dessner’s haunting, ethereal score is performed live by Roomful of Teeth (Cameron Beauchamp, Martha Cluver, Eric Dudley, Estelí Gomez, Abigail Lennox, Thomas McCargar, Thann Scoggin, and Caroline Shaw), joined by soprano Alicia Hall Moran and tenor Isaiah Robinson, the women in silvery white, the men (except for Robinson) in black. (The set and costumes are by Carlos Soto.) Brad Wells conducts, with Jessica McJunkins on violin, Tia Allen on viola, Byron Hogan on cello, Kyra Sims on French horn, Ian Tyson on clarinet and bass clarinet, Laura Barger on piano and harmonium, Donnie Johns and Victor Pablo on percussion, and James Moore on guitar.

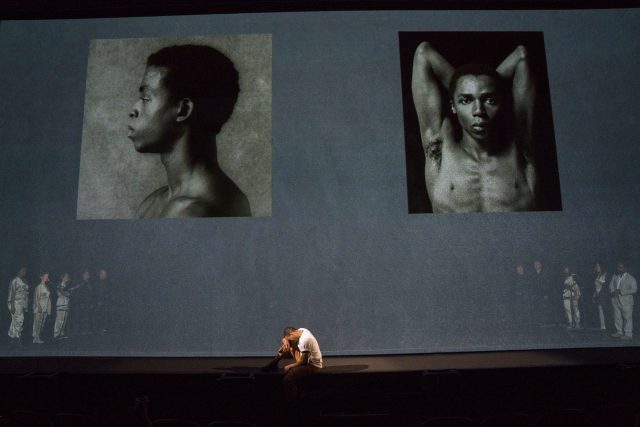

A man cannot look up at Robert Mapplethorpe images in Triptych (Eyes of One on Another) (photo by Richard Termine)

Korde Arrington Tuttle’s libretto boasts numerous phrases that stick in the mind as they are sung and projected on walls and screens: “The devil in us all / darkness as beauty”; “Aesthetics can justify desire”; “unsavory things”; “The Artist machetes a clearance.” However, there are also quotes from the trial, which feel trivial and pedantic, especially when juxtaposed with Robinson and Roomful of Teeth’s extensive later repetition of “In america, / I place my ring / on your cock / where it belongs,” from Hemphill’s American Wedding. Among the photographs are “Dominick and Elliot,” depicting a shirtless white man holding the nether regions of a naked white man tied upside down; Mapplethorpe’s famous 1988 portrait of himself gripping a cane with a skull on it; “Jack Walls,” of a black man pointing a gun above his exposed penis; and “Cedric, N.Y.C.,” in which a black man bows his head, the light and shadows making it look like his right side is black and his left side white.

Director Kaneza Schaal is unable to bring the piece together; the words, music, and imagery feel like separate entities. Through it all, a black man wanders across the stage and into the audience, looking up at the projections, a spectator commenting on the images of black bodies by saying nothing. When the audience enters the Howard Gilman Opera House, he is sitting at the front of the stage, watching the people wander in, implicating us all. But I’m not sure in what.