Sundance-winning documentary reveals the many sides of musician and activist M.I.A.

MATANGA/MAYA/M.I.A. (Steve Loveridge, 2018)

IFC Center

323 Sixth Ave. at West Third St.

Opens Friday, September 28

212-924-7771

www.ifccenter.com

www.miadocumentary.com

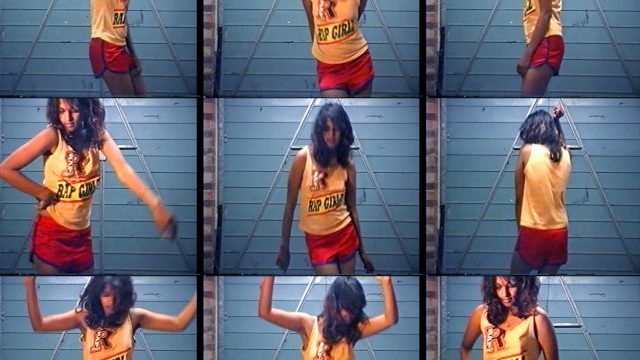

In the mid-1990s, Steve Loveridge and Maya Arulpragasam met at St. Martin’s College and became friends. Over the last twenty years, Loveridge and Maya — better known as M.I.A. — have collaborated on songs and videos, leading up to the documentary Matangi/Maya/M.I.A., an intimate portrait of Arulpragasam, from her childhood days as Matangi in Sri Lanka, where her father was the founder of the Tamil Resistance Movement, to her teen years as Maya, a developing artist, and finally as M.I.A., the controversial music star and political activist who has released such albums as Arular, Kala, and 2016’s AIM, which she claimed would be her last. Maya has been filming herself since she was very young, and she opened up her vast archives to Loveridge, who sifted through nearly nine hundred hours of recordings to make his first film. Loveridge shows Maya working on her music, protesting for peace, and famously raising her middle finger while performing with Madonna at the Super Bowl. M.I.A. is a powerhouse onstage — I was blown away by an October 2007 concert at Terminal Five — but Loveridge reveals her more sensitive and vulnerable sides in addition to her fierce ambition and pride in who she is and where she is from. Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. is now playing at IFC Center; before attending several postscreening Q&As, Loveridge discussed the film with twi-ny, giving thoughtful, extremely honest, and provocative answers to questions about his friendship with Maya, his feelings about the music industry, and his future as a filmmaker.

twi-ny: What was it that first attracted you to Maya at art school?

Steve Loveridge: She was confident. I was very shy and I think she was much better at meeting people, finding ways to access different places. She took me on lots of adventures and made London seem like a playground.

Also, in our work — I think the other students and tutors on the course kind of looked down on pop culture — music videos, TV movies, mainstream film — but Maya and I, being a gay guy and a brown girl, maybe we saw more value and significance in what pop culture could mean and how it could reach and create change in the world because we had personal experience of it changing our ideas of ourselves, helping us have a vision of who we could become, and being a lifeline when we were teenagers and we didn’t have any people the same as us around to guide us in real life.

twi-ny: Could you tell back then that she was primed for international stardom?

sl: Yes. I think everybody’s got a story, everyone is interesting — but if you’re a poor person and don’t have a “way in” to the arts, or any connections, you have to have a special kind of confidence and robustness to go and knock on doors and ask to be let in, because no one’s going to do it for you. She had that. It took a while for her to find the right door, but she was looking for a way in every day.

Steve Loveridge and M.I.A. at New York premiere of documentary at Film Society of Lincoln Center at New Directors/New Films festival (photo by Sean DiSerio)

twi-ny: Do you think it is easier or harder to make a documentary about someone you know so well?

sl: Ordinarily, I’d say it’s harder. I think objectivity is too difficult and I would question the wisdom of a friend making a film about a friend. But in this circumstance I feel like Maya, and her family, and the Tamil community were so jaded and mistrustful of the media and interviewers that this story had to be trusted to someone who had earned that trust on a personal level.

twi-ny: In the film, Maya says that she originally wanted to become a documentary filmmaker, and that is evidenced by how much footage she compiled over the years. Did she ever stray from being the subject and instead act like a director or editor? How involved in the process was she?

sl: It was vital from the outset that she wasn’t involved in the edit at all. Even though we’re friends, just to keep things clear, we got a lawyer and did a contract that said I had final cut and she wasn’t allowed into the edit suite. I think that’s amazing trust on her part — I would never ever let someone do that with my personal videos. Especially as she hadn’t watched most of them for years.

twi-ny: What was it like sifting through her archives?

sl: It was emotional and also very educational — I learnt a lot more about her family story. It also reminded me of why I became her friend in the first place.

twi-ny: Was there anything that she declared was off-limits?

sl: On a couple of the tapes she’s chatting to people about me when she’s in a bad mood, and it’s funny eavesdropping on conversations about you that people had fifteen years ago.

twi-ny: How many hours of footage was available?

sl: It was very difficult to deal with the amount of material. There was about seven hundred hours of vérité filming, one hundred of media archive of M.I.A., about thirty hours of performance. One of the hardest things was watching footage of her and talking about her all day and then also trying to maintain a friendship — it was too much, so we had to take a break from each other for a bit and not really talk much.

twi-ny: Regarding that, there were some issues between you, Maya, and her record label, leading to your posting that you “would rather die than work on this.” How did that all get settled? It certainly appears that you and M.I.A. are on good terms again, if there ever really were problems.

sl: Yeah, the problem wasn’t Maya (although I did think she coulda stepped in and helped me out a bit more — it’s hard for a little filmmaker to deal with Interscope, Roc Nation, and all these music industry people all on your own!).

The basic problem was that I worked on the film for a whole year in 2012, with it funded by Interscope, and then suddenly one day they just stopped the funding — but not in a professional, courteous way; they just didn’t pay their bills, stopped answering the phone, and left the production company just guessing. I got angry that Maya’s management weren’t interested in helping me sort the situation and we had a fight about it.

Part of the frustration was that in 2013, Sri Lanka was controversially chosen to host the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, which felt like a real blow to the Sri Lankan Tamil community in their quest for some kind of accountability for the human rights abuses that had happened at the end of the civil war in 2009.

Maya was really, really keen to get the film out in some form that year, in case it helped raise awareness in some tiny way, so it was difficult feeling blocked by her own team.

In the end, the situation was resolved by scrapping the whole project with the record label. I went away and got a job, forgot about the movie for a year, and then in 2014 we found funding from Cinereach, a New York not-for-profit who had seen the trailer I leaked online and got in touch. We started again from scratch with a whole different approach. Making the film in the independent documentary space instead of from inside the music industry transformed it completely, and I was able to make a film that matched my vision.

So when Maya says the film took seven years, or ten years, like she keeps telling interviewers — it wasn’t all my fault! It really only took from 2014 to 2017, which apparently isn’t that bad for a feature doc, especially as I was a first-timer and had nearly nine hundred hours of material.

twi-ny: Are you fully satisfied with the final product? Is the Maya onscreen the Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. you’ve known for more than twenty years?

sl: I am. It’s definitely only about a certain aspect of her story — I focused on her cultural identity and how she negotiates being all these different things at once, and I think it does a good job at evoking what that feels like to be around. People describe the film as “messy in a good way,” and that’s how she feels. I left out all the gossipy relationship stuff with boyfriends, and it’s not really a traditional music doc in that there’s not much of her artistic process or output other than when it serves the identity narrative. But I feel like her music and art are out there and available for people to discover and dip into as much as they like.

twi-ny: Do you have a favorite song/album/video of hers?

sl: “The Message” is great, on her third album [Maya] — whoever wrote that is a genius. [Ed. note: The song was cowritten by Loveridge with Sugu Arulpragasam, Maya’s brother.] But my favorite is always “Galang” because it was the first thing. When the record label sent us the first pressing, it was so exciting holding a vinyl record in my hand that she’d actually made, and then doing the video with all her stencil artwork in it and seeing it on YouTube, it felt like some kind of validation and like the world was suddenly opening up for us.

twi-ny: This is your first feature documentary; do you plan on making more films in the future?

sl: Maybe — I’d certainly never sign up for something again where I only get paid based on hitting certain stages; making this film has crippled my personal finances, and it’s going to be hard to ever contemplate doing that again! I honestly sometimes feel like filmmaking is really only for rich people. But I love stories and storytelling and maybe I’ve learnt enough about the things that slowed this project down to not make the same mistakes again and I could do it in a way that can work for me creatively and financially.