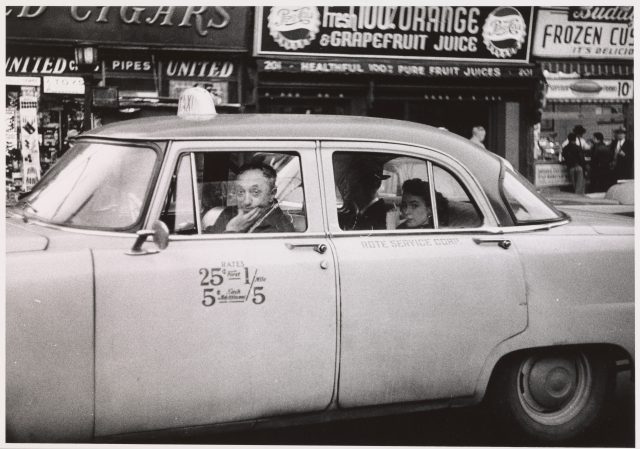

Diane Arbus, “Taxicab driver at the wheel with two passengers,” gelatin silver print, 1956 (© The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC. All Rights Reserved)

The Met Breuer

945 Madison Ave. at 75th St.

Tuesday – Sunday through November 27, suggested admission $12-$25

212-535-7710

www.metmuseum.org

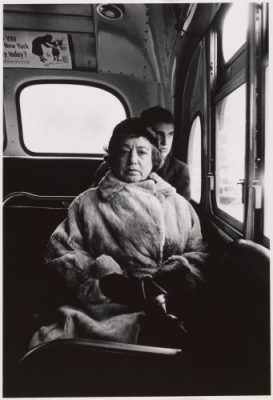

The Met Breuer doesn’t just invite visitors into the early work of photographer Diane Arbus in the sensational show “diane arbus: in the beginning.” It ingeniously immerses them in the world that so attracted the New York City artist in her formative years, allowing museumgoers to make their own path through the people she encountered. “We’re looking at 1956 to 1962, made primarily in New York City, from Times Square to Coney Island to the Lower East Side, the same terrain that so many other artists of the era covered, offer[ing] this artist a new way of understanding who we are and who we might be. You feel the authentic quality of each of the individuals,” curator Jeff Rosenheim says in a Met Breuer video. “She seems to be able to separate the individual from the society. That is the power of a great Diane Arbus picture, that incessant need to know, and to record, and to follow her own eyes to wherever it took her, is defining of her career.” Consisting of more than one hundred works, most of which have never been shown publicly before and were printed by Arbus herself, the exhibition features photographs mounted on two sides of large rectangular stanchions arranged in rows in the gallery, allowing people to weave in and around Arbus’s fascinating landscape. Born in 1923 in New York City, Arbus got her first camera from her husband in 1941. (She was married for twenty-eight years to actor and photographer Allan Arbus, best known for playing psychiatrist Sidney Freedman on the M*A*S*H television series.) By the mid-to-late fifties, Arbus was documenting a wide variety of men, women, and children primarily in New York City as well as sideshow performers in Palisades Park, strippers in Atlantic City, and female impersonators on Long Island. One of her favorite haunts was Hubert’s Dime Museum and Flea Circus, where she photographed freaks, but none of her pictures were exploitative.

Diane Arbus, “Lady on a bus, N.Y.C.,” gelatin silver print, 1957 (© The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC. All Rights Reserved)

“I do feel I have some slight corner on something about the quality of things. I mean it’s very subtle and a little embarrassing to me but I really believe there are things which nobody would see unless I photograph them,” she said. She also noted, “For me the subject of the picture is always more important that the picture. And more complicated.” Most of her subjects were well aware they were being photographed and posed for the camera, although some were caught unaware. In “Miss Stormé de Larverie, the Lady Who Appears to Be a Gentleman, N.Y.C. 1961,” an elegant trans person, cigarette in hand, sits confidently on a park bench. In “Miss Makrina, a Russian Midget, in her kitchen, N.Y.C. 1959,” a small woman pauses while cleaning. In “Kid in a hooded jacket aiming a gun, N.Y.C. 1957,” a child in a winter coat points a gun at the camera. In “Seated female impersonator with arm crossed on her bare chest, N.Y.C. 1960,” the subject is topless, his anatomy clashing with his makeup and hairstyle. And in “A Jewish giant at home with his parents in the Bronx, N.Y. 1970,” a man hunches over, towering above his parents in their living room. There are also photos of a tattooed man, the Human Pincushion, scenes from movies, a family relaxing on their expansive lawn, a trapeze act, and an old lady in a hospital bed nearing her last breath. In the early 1960s, Arbus would switch to a 2¼-inch square-format Rolleiflex camera, continuing to capture a different side of America, but “in the beginning” wonderfully reveals where it all started. “A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know,” Arbus, who committed suicide in 1971 at the age of forty-eight, famously said. The same can be said for this must-experience exhibit.