László Moholy-Nagy, “Room of the Present” (Raum der Gegenwart), mixed media, constructed in 2009 from plans and other documentation dated 1930 (Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, © 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society, New York, photo by David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

1071 Fifth Ave. at 89th St.

Daily through September 7, $25 (pay-what-you-wish Saturday 5:45 – 7:45)

212-423-3587

www.guggenheim.org

“For a new ordering of a new world the need arose again to take possession of the simplest elements of expression, color, form, matter, space,” László Moholy-Nagy wrote in 1922’s “On the Problem of New Content and New Form.” That belief is on spectacular display in “Moholy-Nagy: Future Present,” which continues at the Guggenheim through September 7. The first major U.S. retrospective of the Austria-Hungary–born utopian modernist in nearly half a century, the show is a natural fit for the swirling ramp of Frank Lloyd Wright’s building, unfurling chronologically as Moholy-Nagy (1895 – 1946; pronounced “muh-HOH-lee nahj) experimented with an ever-widening range of artistic disciplines, melding art, technological innovation, utilitarian design, science, and social transformation. The exhibit begins with a kind of preface, Moholy-Nagy’s “Room of the Present,” which was never realized in his lifetime. The Gesamtwerk (“total work”) features films by Viking Eggeling, Sergei Eisenstein, and Dziga Vertov, photographic slides, posters, sculptures, architectural designs, and, in a box in the center, a re-creation of Moholy-Nagy’s most famous work, the kinetic “Light Prop for an Electric Stage.” It’s an excellent preparation for what follows, more than three hundred diverse works that appear tailor made for the Guggenheim space — in fact, his work is part of the museum’s founding collection (courtesy of Hilla Rebay) and was included at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, the forerunner of the Guggenheim.

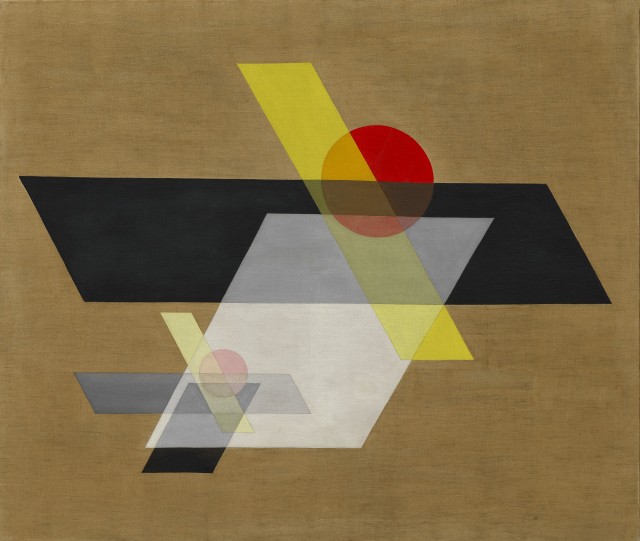

László Moholy-Nagy, “A II (Construction A II),” oil and graphite on canvas, 1924 (© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society, New York)

Moholy-Nagy, who was also a writer and Bauhaus teacher who left Europe for good in 1937 and moved to Chicago, where he started the New Bauhaus, today’s Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology, produced enamel paintings with abstract geometric forms, haunting camera-less photograms, striking typography, avant-garde film, theater and opera stage design, collages using cut-outs resulting in seemingly impossible perspective, and three-dimensional works using such industrial materials as Trolit, Formica, Plexiglas, and Galalith. The exhibition is like marching in a parade of eye-opening creativity, all from the vision of one man. “Dual Form with Chromium Rods” hangs from above, like an imaginary space station. The oil and graphite painting “A 19” captures the essence of Moholy-Nagy’s fascination with color and geometry. “Photogram,” from 1926, reveals the large hand of the artist. “Space Modulator” (1939-45) and “Papmac” feature lines incised on Plexiglas and paint on both the inside and the outside of the plastic. “Slide” is a manipulation in which the Tiller Girls dance troupe appears to be racing down an imaginary slide in a way that would make Busby Berkeley proud. And finally, when you arrive at the top, you get to go back down again, experiencing Moholy-Nagy’s breathtaking oeuvre in reverse; while that is true, of course, for every Guggenheim show, it’s a real joy going backward through this particular artist’s forward-thinking process. “If the unity of art can be established with all the subject matters taught and exercised, then a real reconstruction of this world could be hoped for — more balanced and less dangerous,” Moholy-Nagy wrote in 1943’s “The Contribution of the Arts to Social Reconstruction.” The exhibit, one of the best of 2016, is on for only a few more days; it would be a shame to miss it. It’s also a shame that Moholy-Nagy died of leukemia in 1946 at the age of fifty-one; it would have been thrilling to see what he could have done in the ensuing years, as technological innovation spiraled in the aftermath of WWII.