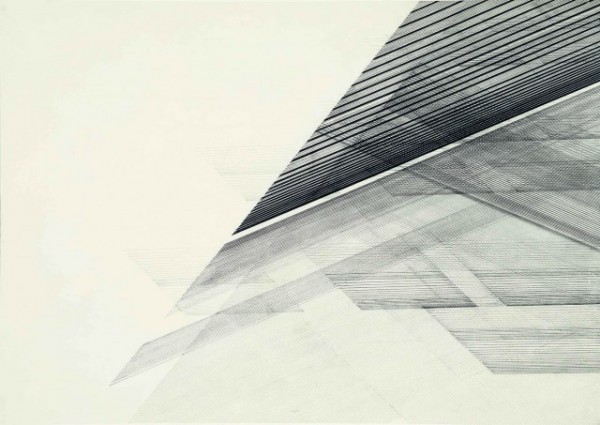

Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled, ink and graphite on paper, ca. 1975 (Sikander and Hydari Collection)

The Met Breuer

945 Madison Ave. at 75th St.

Friday, June 3, free with suggested museum admission, 6:00

Exhibition continues through June 5

212-731-1675

www.metmuseum.org

The Met Breuer instantly established its own identity in March, when it opened in the old Whitney space with an experimental performance residency by jazz great Vijay Iyer and an eye-opening exhibition on little-known Indian artist Nasreen Mohamedi, along with the major show “Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible,” which more than hinted at further changes to come at this new outpost. On Friday, June 3, the Met Breuer will host the MetFridays lecture “The Maximum Out of the Minimum: Reconsidering Nasreen Mohamedi,” with University of Washington associate professor Sonal Khullar, artist Seher Shah, and Sheena Wagstaff, Met chairman of the Departments of Modern and Contemporary Art. “It’s an odyssey of an artist who, despite all the difficulties, was intent on creating work that really made a difference, and that is both personally very impressive but was artistically, well, you can see for yourself,” Wagstaff says in the exhibition trailer. The Indian artist’s first U.S. museum retrospective features more than 130 drawings, paintings, photographs, and diaries by Mohamedi, who died in 1990 at the age of fifty-three but continued working to the end of her life despite battling a rare neurological disorder. Mohamedi favored sharp horizontal and diagonal lines, polygonal shapes, and grids that explored light and space. The progression of her career took her from abstract ink-and-watercolor works on paper to gelatin silver prints of outdoor locations with unique linear angles to extraordinary ink-and-graphite drawings that eventually took on a scientific, futuristic quality, very different from what her contemporaries were doing in South Asia and beyond.

Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled, gelatin silver print, ca. 1972 (Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi)

All of the works are untitled, allowing viewers to supply labels in their own thought processes if they choose. Mohamedi’s creativity and imagination are so compelling, you’re likely to wonder why you’re hearing about her only now, more than a quarter century after her death, although a critical reevaluation has been building over the last ten years. She was inspired by the writings of Rainer Maria Wilke and Albert Camus and the architectural work of Le Corbusier as well as by Kasimir Malevich and Wassily Kandinsky and fellow Indian artists M. F. Husain, Tyeb Mehta, and V. S. Gaitonde but amassed an oeuvre that was uniquely her own. In her 2014 poetic essay “Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved,” the artist’s friend Geeta Kapur wrote, in conjunction with a show at the Tate, “Remember Nasreen’s frail limbs, ascetic face, ungendered artist persona. Remember her calling as an unrequited beloved, her narcissistic engagement with her body and the stigmata she barely cared to hide. And always her departing gesture, her return, her masochism and its reward of absurdity and grace. Her continual tracking of a mirage.” You can experience all this more at this beautiful exhibition, with the June 3 panel discussion a happy bonus. “A precise specularity, the flight of an angel shearing space. Then, in the dark night of the soul, where the ejected body persists, Nasreen was content to work with a poverty of means,” Kapur, an influential art critic, adds. “To counter the spectacle of love and of spiritual ambition, she was willing to break apart. She would simply survive, and let the calligraph, the graphic sign, speak.”