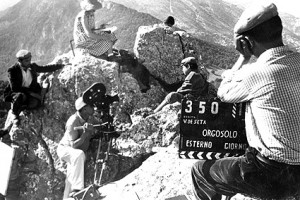

Sardinian brothers Michele (Michele Cossu) and Peppeddu (Peppeddu Cuccu) are on the run from the law in Vittorio De Seta’s BANDITI A ORGOSOLO

BANDITI A ORGOSOLO (BANDITS OF ORGOSOLO) (Vittorio De Seta, 1961)

Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater

144 West 65th St. between Eighth Ave. & Broadway

Saturday, May 23, 7:00

Festival runs May 22-31

212-875-5050

www.filmlinc.com

“The souls of these men are still primitive. What is right according to their law is not right according to that of the modern world,” an unseen narrator explains at the beginning of Vittorio De Seta’s sadly overlooked debut feature, Banditi a Orgosolo, about shepherds scraping to get by in a vast mountainous region of Sardinia. In the black-and-white post-neorealist film, Michele (Michele Cossu) and his young brother, Peppeddu (Peppeddu Cuccu), tend to their flock of sheep, for which Michele still owes money. After a trio of former shepherds turned bandits shows up, Michele is visited by the police; not wanting to get involved, he lies to the carbinieri, insisting he has not seen anyone else. A firefight ensues between the police and the bandits, leaving one cop dead, and Michele and Peppeddu are on the lam, hunted by the police while desperately trying to hold on to their flock as they make their way through what Michele refers to as “bad places.” Winner of the New Cinema Award at the 1961 Venice Film Festival, Banditi a Orgosolo is a dark, bleak tale, shot by De Seta in nearly infinite gradations of black and white, Valentino Bucchi’s ominous score lurking in the background. Cossu, a nonprofessional actor from the region, portrays Michele with a stark earnestness and a clear understanding of the futility of his character’s situation. A former documentarian, De Seta (The Uninvited, Lettere dal Sahara), who wrote the screenplay with Vera Gherarducci, doesn’t make any epic proclamations about society’s ills, instead letting the story about changing times and abject poverty in Sardinia unfold at an often agonizing snail’s pace. The shepherds and their small villages, representative of the old ways, are being left behind, even as the state takes the place of centuries-old oppressors, doing what it can to keep them down and destitute.

“The souls of these men are still primitive. What is right according to their law is not right according to that of the modern world,” an unseen narrator explains at the beginning of Vittorio De Seta’s sadly overlooked debut feature, Banditi a Orgosolo, about shepherds scraping to get by in a vast mountainous region of Sardinia. In the black-and-white post-neorealist film, Michele (Michele Cossu) and his young brother, Peppeddu (Peppeddu Cuccu), tend to their flock of sheep, for which Michele still owes money. After a trio of former shepherds turned bandits shows up, Michele is visited by the police; not wanting to get involved, he lies to the carbinieri, insisting he has not seen anyone else. A firefight ensues between the police and the bandits, leaving one cop dead, and Michele and Peppeddu are on the lam, hunted by the police while desperately trying to hold on to their flock as they make their way through what Michele refers to as “bad places.” Winner of the New Cinema Award at the 1961 Venice Film Festival, Banditi a Orgosolo is a dark, bleak tale, shot by De Seta in nearly infinite gradations of black and white, Valentino Bucchi’s ominous score lurking in the background. Cossu, a nonprofessional actor from the region, portrays Michele with a stark earnestness and a clear understanding of the futility of his character’s situation. A former documentarian, De Seta (The Uninvited, Lettere dal Sahara), who wrote the screenplay with Vera Gherarducci, doesn’t make any epic proclamations about society’s ills, instead letting the story about changing times and abject poverty in Sardinia unfold at an often agonizing snail’s pace. The shepherds and their small villages, representative of the old ways, are being left behind, even as the state takes the place of centuries-old oppressors, doing what it can to keep them down and destitute.

Banditi a Orgosolo is getting a rare screening on May 23 at 7:00 as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center series “Titanus: A Family Chronicle of Italian Cinema,” a ten-day, twenty-three-film retrospective honoring the Italian production company founded by Gustavo Lombardo in 1904 and later run by his son, Goffredo, and grandson, Guido, that remained active until 1964 (although it continues to occasionally release work). The festival displays the wide range of Titanus’s output, including Michelangelo Antonioni’s Le Amiche, Dario Argento’s The Bird with Crystal Plumage, Ermanno Olmi’s The Fiancés, Francesco Rosi’s The Magliari, Elio Petri’s Numbered Days, Federico Fellini’s The Swindle, Steno’s Totò Diabolicus, and Vittorio De Sica’s Two Women, but not Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard; the tremendous cost of filming Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s epochal novel played a major role in the company’s downward fortune.