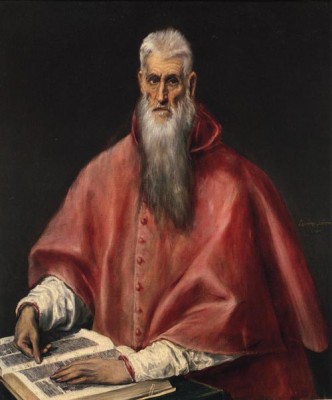

El Greco, “St. Jerome,” oil on canvas, 1590-1600, Henry Clay Frick Bequest (photo by Michael Bodycomb)

EL GRECO AT THE FRICK COLLECTION

The Frick Collection

1 East 70th St. at Fifth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through February 1, $20 (pay-what-you-wish Sundays 11:00 am – 1:00 pm)

212-288-0700

www.frick.org

In the summer of 2008, the Frick moved six of its masterpieces from the Living Hall to the Oval Room while the former was being refurbished, offering art lovers the opportunity to view such Frick favorites as Hans Holbein the Younger’s breathtaking “Sir Thomas More” and El Greco’s marvelous “St. Jerome” in close conjunction and different surroundings, giving them a kind of new lease on life. In celebration of the quadricentennial of the death of Crete-born artist Domenikos Theotokopoulos, better known as El Greco, the Frick has moved all three of its paintings by the Spanish master into the Oval Room: “St. Jerome,” “Vincenzo Anastagi,” and “Purification of the Temple.” Presented side by side for the first time ever, the trio forms a striking triumvirate. In the center, above the fireplace, stands Italian knight Vincenzo Anastagi, wearing armor over his upper body and puffy green pantaloons, his helmet on the floor to his left, an open window barely visible to his right, his sword oddly showing through between his legs, a curtain behind him creating geometric shapes in the background. He is both mysterious and dignified. On one side of “Vincenzo Anastagi” is a rare religious scene purchased by Henry Clay Frick, “Purification of the Temple,” a small, richly dense, boldly colorful depiction of Christ throwing the moneychangers out of the temple. To Christ’s right are sinners, a relief of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden above them; to his left are his believers, a relief of Abraham about to sacrifice Isaac above them. El Greco’s brushwork dazzles in this compact, claustrophobic, emotionally powerful work. Meanwhile, on the other side of “Vincenzo Anastagi” resides “St. Jerome,” the biblical translator looking just away from the viewer. His head, ears, nose, gray-white beard, and fingers are elongated, his red robe sharply defined against a dark background. Up close, one can revel in the folds of his clothes, the touch of color peeking through the end of his white sleeves, his left thumb placed firmly in the margin of the Bible in front of him. His face is craggy and wrinkled, with dark, deep-set eyes and sunken cheekbones. The painting is centered by the vertical buttons running down St. Jerome’s robe, pulling at the viewer. It’s a striking portrait that is a joy to behold in this new setting, like experiencing it again for the first time.

El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos), detail, “View of Toledo,” oil on canvas, ca. 1598–99 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H. O. Havemeyer Collection)

EL GRECO IN NEW YORK

Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Ave. at 82nd St.

Gallery 608

Through Sunday, February 1, recommended admission $25

212-535-7710

www.metmuseum.org

A later version of El Greco’s portrait of St. Jerome, “Saint Jerome as Scholar,” is part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “El Greco in New York,” which brings together all of their El Greco holdings along with those from the Hispanic Society of America, collected by Archer Huntington. The Met’s pieces are highlighted by the unfinished and truncated “The Vision of Saint John,” in which the apostle, in blue dress, dominates the left side of the frame, holding his hands up to the heavens, the color palette similar to the Frick’s “Purification of the Temple”; “Cardinal Fernando Niño de Guevara,” a portrait of the Spanish inquisitor in elegant dress sitting in a chair, his hands dangling over the armrests, with ornate wallpaper behind him and a sheet of paper at his feet, looking as if he is ruing what he has to do next; and “View of Toledo,” one of the greatest landscapes in art, with dark, foreboding clouds hovering over lush green fields and gray buildings, a condensed, ominous depiction of “the Holy City.” The Hispanic Society works include “Pietá,” showing Christ being carried in the center, the three crosses nearly hidden at the upper left, his mother in agony behind him; “The Holy Family,” with the baby Jesus nursing at his mother’s teat; the rare miniature “Portrait of a Man”; and “Saint Francis,” a side view of the friar that was originally part of a larger canvas. Over the course of the more than four hundred years since El Greco began painting, his work has been in and out of style, forgotten and rediscovered, widely hailed and sinfully dismissed. But the gathering of all his paintings in New York, from the Frick, the Met, and the Hispanic Society, reveal him to be a man ahead of his time, an artist whose influence continues to grow.