Bernardí Roig’s “The Mirror (exercises to be another)” will continue to intrigue visitors at Claire Oliver through January 11 (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

BERNARDÍ ROIG: THE MIRROR (exercises to be another)

Claire Oliver

513 West 36th St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

Through January 11, free, 10:00 am – 6:00 pm

212-929-5949

www.claireoliver.com

The centerpiece of Spanish artist Bernardí Roig’s latest exhibition at the Claire Oliver Gallery in Chelsea, “The Mirror (exercises to be another),” is the all-white title work, a sculpture of two men on a platform facing each other as if looking in a mirror, a bright fluorescent light both blinding and dividing them. Cast in polyester resin and marble dust, the men stand barefooted, their bellies hanging over their unbuttoned pants, one of the figures with his fingers in his ears, the other having apparently just ripped off part of his face, including his mouth and an eye. It’s a wry comment on one of Roig’s primary themes, people’s inability to communicate in contemporary society, slyly referencing the iconic “See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil” trope, while also engaging in a search for truth and reality, as one man is a distorted version of the other. In the far corner, “The Invisibility of Memory (La invisibilidad de la memoria)” features a similar white figure (though with a third arm), his head downtrodden, his body defeated, hanging from a metal frame that holds a video screen showing unclear images that eventually fade away. Roig also includes fourteen charcoal drawings, inspired by Ingres’ “Portrait of Monsieur Bertin” and Federico de Madrazo’s “Portrait of Gertrudis G. de Avellaneda,” which, like the sculptures, examine identity through the subject, the viewer, and the artist.

Roig, who was born in Palma de Mallorca and had the first show in this space back in 2002 — he’s been with Claire Oliver for fourteen years — recently said, “Images are like the foam of the subconscious mind.” Although his sculptures are instantly engaging, extremely pleasing to the eye, they are loaded with deeper meaning, inviting those who gaze upon them to go well beyond the surface. “It is gratifying to see the response to his work from curators, critics, and collectors alike; we have watched him grow as an artist and are proud to represent his works,” Oliver told twi-ny. “Working with the artist is a pleasure; Roig is highly intellectual but remains grounded and humorous as well. His thought process is deliberate and the works produced, without exception, are of the highest quality.” A provocative thinker with a strong art-historical bent, Roig discussed language, dialogue, running out of ideas, and the human body while staying in New York City with his family during the run of the show, which closes January 11.

twi-ny: What was your initial impetus behind creating all-white sculptures cast from real people? Do you have favorite models?

Bernardí Roig: I started by casting my father’s body, which was what was closest at hand, to address the symbolic figure of the great castrator. It was a big, heavily built body . . . and then afterwards there came other similar ones, always bulky and always people connected to me. Once positivized, they are white for two reasons: firstly, to gain in visual lightness and refute their affirmative and statuary quality so that they are simply images and, secondly, to help me detain the moment. Sculpture is an instant trapped in a form. All Goethe’s Faust can be reduced to one single sentence: “Time stands still! You are so beautiful. . . .” Only then does one understand that the moment is white. This brooks no doubt. And in all certainty it is white, because light, once stilled, coagulates. We might then say that the gaze has been submerged in a glass of milk, and in this glass of milk we recognize the annunciation of a form of knowledge where the signifieds have still not copulated.

twi-ny: These white figures, especially when bright light is projected onto them, are a kind of blank slate, setting up a potentially wide-open, complex dialogue between object and viewer. While some of your regular themes involve blindness, death, and the individual’s uneasy search for identity, there is something inherently aesthetically pleasing about your sculptures; people immediately react with happiness upon seeing them. Is there an intended contradiction there?

BR: I’d say that the intentions are contradictory because they are made of opposites, just like our thoughts. The themes my work engages with are by no means strange; they are embedded in the medulla of all thinking people. I’m not very sure of people’s relationship with my work. It’s hard to really tell, and I imagine that the spectrum of readings is as wide as the number of individual spectators. The images we make come from deep down, from far back, and they rise like foam to the surface of the unconscious.

Language was invented to try to bridge the gap of noncommunication, but it obviously falls short. I also accept that a convulsive image can produce a feeling of happiness, something that also happens with Surrealism.

twi-ny:The exhibition at Claire Oliver also features charcoal drawings, including several based on Ingres’ “Portrait of Monsieur Bertin” and Madrazo’s “Portrait of Gertrudis G. de Avellaneda.” What struck you about those two portraits?

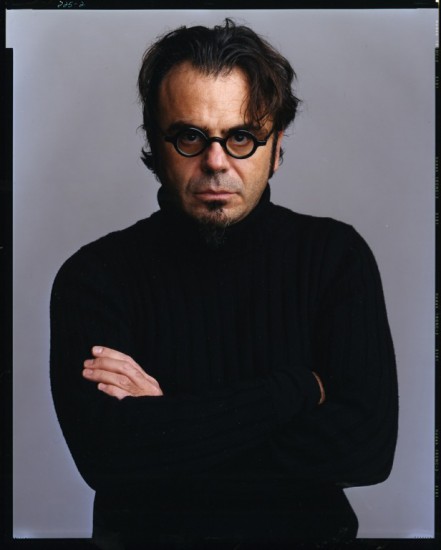

Bernardí Roig explores language, communication, the human body, and more in latest exhibit (photo by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders)

BR: I started out from two historic paintings to make this new series of fourteen large drawings which I’ve called “Je est un autre.” Seven male portraits reinterpreting the “Portrait of Monsieur Bertin” by Ingres (1832), housed in the Louvre, facing seven female portraits reinterpreting the “Portrait of Gertrudis G. de Avellaneda” (1857) by Madrazo, on view at the Lázaro Galdiano Museum in Madrid. The title of the series, “Je est un autre,” is a celebrated sentence from Rimbaud’s Lettre du voyant (“Letter of the Seer”) to his friend Paul Demeny, where the poet accepted the loss of identity and splitting of the self through negation.

These fourteen drawings play with the superimposition of reflected identities, revealing how any representation of identity contains the latent experience of its opposite. “Monsieur Bertin” is a frontal depiction of a bourgeois man, opulent, arrogant and powerful, even more powerful than the emperor himself, while Gertrudis de Avellaneda is an enlightened, cosmopolitan Spanish poet, born in Cuba, who represents female resistance to the hermetic, masculine, and oppressive academic world in Spain in the mid-nineteenth century.

twi-ny: For “Instante Blanco,” which is currently at el Museo Nacional de Escultura, you placed your white sculptures among the institution’s polychrome works, creating a kind of intervention. Are you pleased with the way it turned out? Do you plan on doing more of these types of installations?

BR: The use of polychrome is in search of realism, to bring the carved wood closer to the truth, to try to produce belief through a whole itinerary marked out by the palpability of the flesh. Most of the works in the Museo Nacional de Escultura were originally devotional religious images whose contemplation held out some kind of guarantee. What I proposed was an itinerary of whispered dialogues with the space itself and not so much with the works.

When you work with historic museum spaces you expand the boundaries of experience. Each exhibition I do has to produce the unforeseen. Though my works hit you immediately as sculptures, I work above all with places and for each place I pose different questions. But I don’t try to answer them. I don’t believe that the purpose of art is to come up with answers but perhaps to hone the incisiveness of the questions.

I’ve already done these kinds of interventions in the Cathedral of Burgos, in Cà Pesaro Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna at the fifty-fourth Venice Biennale, and at the Lázaro Galdiano Museum in Madrid, and at the current moment I am working on a project for the “Intersections” program at the Phillips Collection in Washington.

twi-ny: You’re often quite critical of your own work. You recently said, “I have the feeling that I am always repeating the same ideas and that I am incapable of saying new things. . . . Every time you want to delay more the moment of showing anything, but you have to do it.” Is it difficult for you to let go and open a new exhibition? Is it hard for you to accept praise? The general public, and critics, seem to take pure delight in your work.

BR: It’s true that I find it increasingly more difficult to add something to what has already been said. . . . The edges of words are more and more frayed all the time. That said, it is equally true that you are part of a chain of images from which you can’t escape, and that’s why it is better to get them out of your head before they explode inside it. These images are often only leftover scraps that the head spits out; other times they have the necessary density to guarantee the meaning of the work, just at the moment when the unforeseen appears. That would be the most fertile ground. As Guido, the character played by Marcello Mastroianni in Fellini’s 8½, says: “I really have nothing to say, but I want to say it all the same.”

twi-ny:You just spent the holidays in New York, and now you’ve gotten to see the city blanketed with snow, in a way emulating your sculptures. How are the holidays different in New York than in Mallorca?

BR: There’s one big difference: right now in New York there is a major exhibition of an artist who, in a place infested by banal low-intensity images, makes you believe again in grand Art: Richard Serra. It is worthwhile living in a world where an artist can still produce a shiver in the gaze.