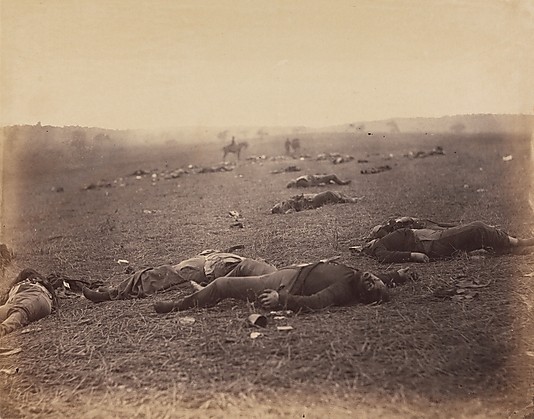

Timothy O’Sullivan, “A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania,” albumen silver print from glass negative, 1863 (Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Ave. at 82nd St.

Through August September 2, $25 adults, children under twelve free

212-535-7710

www.metmuseum.org

“First, a warning shot from the battlefield,” curator Jeff L. Rosenheim begins in the “Shadows of Ourselves” prologue to the catalog that accompanies the expansive exhibition “Photography and the American Civil War,” which continues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through September 2. “This book is not a history of the Civil War, but rather an exploration of the role of the camera at a watershed moment in American culture.” Held in commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, the wide-ranging show features more than two hundred images taken at the dawn of the art of photography, by such early camera enthusiasts as Timothy H. O’Sullivan, soldier A. J. Russell, Mathew B. Brady, George N. Barnard, and Alexander Gardner. The works include tintype studio portraits, battlefield scenes, a close-up of a runaway slave’s flayed skin, medical procedures including amputation, a haunting “Burial Party” of skeletons, a shocking photo of an “Emaciated Union Soldier Liberated from Andersonville Prison,” and shots of such key figures as Sojourner Truth, Robert E. Lee, and Abraham Lincoln.

![Unknown, “[Captain Charles A. and Sergeant John M. Hawkins, Company E, ‘Tom Cobb Infantry,’ Thirty-eighth Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry],” ambrotype, 1861-62 (David Wynn Vaughan Collection)](https://twi-ny.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/photography-american-civil-war-e1377517263437.jpg)

Unknown, “[Captain Charles A. and Sergeant John M. Hawkins, Company E, ‘Tom Cobb Infantry,’ Thirty-eighth Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry],” ambrotype, 1861-62 (David Wynn Vaughan Collection)

Combining pure reportage with an artistic bent, the photographs changed the way the public saw the war, and themselves. As printer and photographer Andrew Gardner wrote in a caption for O’Sullivan’s “A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania,” which depicts a field of fallen solders, “Such a picture conveys a useful moral: It shows the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry. Here are the dreadful details! Let them aid in preventing such another calamity falling upon the nation.” These images also went on to influence such twentieth-century social realist photojournalists as Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. In addition, the availability of cameras and portrait studios allowed the soldiers to pose for a kind of ID card that could be used to both identify them and show to their families, in full dress regalia. “Photography and the American Civil War” provides a gripping view of the war itself as well as the new ways it was being portrayed. The companion exhibition, “The Civil War and American Art,” comprising approximately sixty paintings (and another eighteen photographs) made between 1852 and 1877 by such artists as Frederic E. Church, Sanford R. Gifford, Winslow Homer, and Eastman Johnson, also runs through September 2.