Tuesday, April 3, WORD, 126 Franklin St., free (advance RSVP requested), 718-383-0096, 7:00

Thursday, April 5, Tenement Museum, 103 Orchard St., free (advance RSVP requested), 212-982-8420, 6:30

Saturday, April 28, and Sunday, April 29, MoCCA Festival, 69th Regiment Armory, 68 Lexington Ave., times TBA

Illustrator and cartoonist Leela Corman makes her graphic novel debut with Unterzakhn (Schocken, April 3, $24.95), a dramatic tale of twin sisters coming-of-age on the Lower East Side in the early twentieth century. Young Esther Feinberg gets a job working for a burly woman who operates a burlesque theater and a brothel, while Fanya starts helping out an elegant female obstetrician who also performs illegal abortions. The gripping family drama takes on an added poignancy knowing that Corman and her husband, cartoonist Tom Hart (How to Say Everything), recently suffered a horrific tragic loss, shortly after moving from New York City to Gainesville, Florida. (Hart writes about it here.) Corman will be at WORD in Brooklyn on April 3 for the official launch of Unterzakhn, and she will follow that up with a Tenement Talk at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum on April 5. She will also be signing copies of the book at the MoCCA Festival, taking place April 28-29 at the 69th Regiment Armory. We recently discussed graphic novels, a woman’s right to choose, and belly dancing with Corman.

twi-ny: Unterzakhn is reminiscent of such other graphic novels as Persepolis and Fun Home, yet while both of those were deeply personal memoirs, your book is fiction (but feels like a family memoir). Are there personal memories that can be found in Unterzakhn that you’re willing to share here? Or are the stories and characters a complete fiction?

Leela Corman: The books you mention are works of urgent personal and historical memoir. They are in a different genre. I’m a fiction writer. I think it does fictional comics a disservice to constantly refer back to autobiography, and I wonder why people always seem to expect comics to be autobiographical now. I don’t think it’s a good thing, though I love both books you mentioned, so this is not to take away from those works. Fictional storytelling pulls from all areas of a writer’s life, including (and especially) the imagination. No, there are no significant, specific personal memories in Unterzakhn. Some characters are inspired by people I’ve known, but that would be about 5-10% “real person” and 90-95% fictional character — or more. There’s an alchemical process when creating fiction. Memoir is a different art form, with its own processes. I’m worried that serious fiction in comics is being undervalued, and that anything autobiographical is getting attention, whether it’s interesting or not.

As I said above, I’m not sure that the focus on autobiography is always such a good thing for comics. There are a few places where it works well: 1) When learning to write and draw comics; this would be student work, and is not always for public consumption. 2) When someone REALLY has something to say, and can tie their personal experience to something important happening in the world — Fun Home, MAUS, Persepolis. 3) When someone can turn their personal observations into something interesting for the rest of us, and can avoid solipsism. Great examples of this are Vanessa Davis, who is hilarious and universal, and John Porcellino, who is a poet of observation. 4) If you’re Lynda Barry. She can do anything.

Belly dancer and cartoonist Leela Corman returns to her native New York to talk about her new book, UNTERZAKHN

twi-ny: Unterzakhn comes along at a critical moment in American society, when abortion clinics and organizations such as Planned Parenthood are coming under more fire than ever in the political arena. Did that specifically influence the creation of the book? How do you feel about what’s going on in the country regarding a woman’s right to choose what to do with her body?

Leela Corman: I initially started this project in 2003, and that was my explicit goal, to explore the consequences of not having a choice. If you are a woman in this society, these rights have always been threatened, and this conflict has always been hot. There’s very little difference to me between the discourse in 2012, and the discourse in the ’80s and ’90s, when I was growing up. I’ll wager that every woman my age has older relatives who had to have illegal abortions, unwanted pregnancies, or both. There is absolutely NO excuse for anyone in the public sphere, especially men, to have any say whatsoever in what women do with their bodies. My feelings can be summed up by a photo I saw recently of a woman about my mom’s age holding a sign that read, “I cannot BELIEVE I still have to protest this shit.”

The story eventually moved away from this subject matter, but it is clearly part of the base of the book. I’m glad it’s visible, beneath the tulle and the hair pomade. These issues may be used as political chess pieces by men, but for women, they’re the urgent stuff of our daily lives. We owe much more than we realize to the women who fought not only for our right to a safe abortion (because women will have them, legal or not) but for our right to plan and control how many children we have. We shouldn’t ever take it for granted. Whatever freedoms any of us have, in general, someone else fought and died for them.

By the way, they’re women’s health care clinics, for the most part, not simply “abortion clinics.” Reducing women’s health care centers to “abortion clinics” is inaccurate. Planned Parenthood offers prenatal care for women who want to be pregnant, as well as general women’s health care. When I was in college, they were the only clinic I could afford to go to. I wouldn’t have had any medical care if not for them. The Planned Parenthood clinic I regularly went to for my general medical care was the one that that turd from New Hampshire attacked, about a week after one of my appointments, in fact. He killed the receptionist, and possibly more people, I don’t remember every detail. [Ed note: On December 30, 1994, John Salvi killed receptionist Shannon Lowney in a Planned Parenthood clinic in Brookline, Massachusetts.]

twi-ny: A lot of your illustration work has dealt with women’s undergarments, including Underneath It All, and Unterzakhn translates as “Underthings.” What draws that subject to you?

Leela Corman: Underneath It All was a commission. I’m an illustrator. I work on assignment and can’t control what people think my style is appropriate for. I do what people pay me to, in that realm of my life.

twi-ny: You’re also a professional belly dancer. How did you get into that?

Leela Corman: Quite accidentally. I went to a Moroccan restaurant on Atlantic Avenue that no longer exists, I think, and was pulled up to dance by the house dancer. I just imitated her, and afterwards I thought, hmm, This is fun, maybe I’ll take a class. When I got laid off from my job at Thirteen, I had time, so I signed up for classes at the Greenpoint Y, across the street from my house. The teacher happened to be Ranya Renee, who coincidentally happened to be the perfect teacher for me; she became my mentor, and really turned me into a dancer. I didn’t expect to fall in love with classical Arabic music, and with Egyptian dance in particular, but I did, and I turned out to have a natural ability to do it.

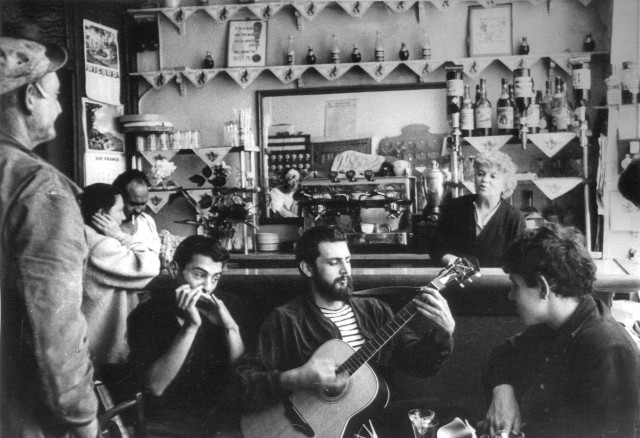

Jean-Pierre Léaud gives a bravura performance in Jean Eustache’s Nouvelle Vague classic about love and sex in Paris following the May 1968 cultural revolution. Léaud stars as Alexandre, a jobless, dour flaneur who rambles on endlessly about politics, cinema, music, literature, sex, women’s lib, and lemonade while living with current lover Marie (Bernadette Lafont), obsessing over former lover Gilberte (Isabelle Weingarten), and starting an affair with new lover Veronika (Françoise Lebrun), a quiet nurse with a rather open sexual nature. The film’s three-and-a-half-hour length will actually fly by as you become immersed in the complex characters, the fascinating dialogue, and the excellent performances. Much of the movie consists of long takes in which Alexandre shares his warped view of life and art in small, enclosed spaces, the static camera focusing either on him or his companion. The Mother and the Whore is screening on April 3 at 7:30 as part of FIAF’s retrospective of the fifty-plus-year career of French New Wave star Lafont, which also includes Claude Chabrol’s The Good Time Girls, Nelly Kaplan’s A Very Curious Girl, François Truffaut’s The Mischief Makers and Such a Gorgeous Girl Like Me, and Olivier Peyon’s Stolen Holidays. Lafont will be at FIAF on April 17 to participate in a Q&A following the April 17, 7:00, Truffaut double feature and will also read published and unpublished letters from Truffaut (in French) on April 18 in Le Skyroom.

Jean-Pierre Léaud gives a bravura performance in Jean Eustache’s Nouvelle Vague classic about love and sex in Paris following the May 1968 cultural revolution. Léaud stars as Alexandre, a jobless, dour flaneur who rambles on endlessly about politics, cinema, music, literature, sex, women’s lib, and lemonade while living with current lover Marie (Bernadette Lafont), obsessing over former lover Gilberte (Isabelle Weingarten), and starting an affair with new lover Veronika (Françoise Lebrun), a quiet nurse with a rather open sexual nature. The film’s three-and-a-half-hour length will actually fly by as you become immersed in the complex characters, the fascinating dialogue, and the excellent performances. Much of the movie consists of long takes in which Alexandre shares his warped view of life and art in small, enclosed spaces, the static camera focusing either on him or his companion. The Mother and the Whore is screening on April 3 at 7:30 as part of FIAF’s retrospective of the fifty-plus-year career of French New Wave star Lafont, which also includes Claude Chabrol’s The Good Time Girls, Nelly Kaplan’s A Very Curious Girl, François Truffaut’s The Mischief Makers and Such a Gorgeous Girl Like Me, and Olivier Peyon’s Stolen Holidays. Lafont will be at FIAF on April 17 to participate in a Q&A following the April 17, 7:00, Truffaut double feature and will also read published and unpublished letters from Truffaut (in French) on April 18 in Le Skyroom.

The annual New Directors, New Films series, a joint presentation of MoMA and the Film Society of Lincoln Center, has been highlighting works by up-and-coming international directors for more than forty years. But the 2012 slate of films includes one intriguing surprise: Stanley Kubrick’s 1953 seldom-seen psychological war drama, Fear and Desire. Kubrick’s first full-length film, made when he was twenty-four, is a curious tale about four soldiers (Steve Coit, Kenneth Harp, Paul Mazursky, and Frank Silvera) trapped six miles behind enemy lines. When they are spotted by a local woman (Virginia Leith), they decide to capture her and tie her up, but leaving Sidney (Mazursky) behind to keep an eye on her turns out to be a bad idea. Meanwhile, they discover a nearby house that has been occupied by the enemy and argue over whether to attack or retreat. Written by Howard Sackler, who was a high school classmate of Kubrick’s in the Bronx and would later win the Pulitzer Prize for The Great White Hope, and directed, edited, and photographed by the man who would go on to make such war epics as Paths of Glory, Full Metal Jacket, and Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Fear and Desire features stilted dialogue, much of which is spoken off-camera and feels like it was dubbed in later. Many of the cuts are jumpy and much of the framing amateurish. Kubrick was ultimately disappointed with the film and wanted it pulled from circulation; instead it was preserved by Eastman House in 1989 and restored twenty years later, which is good news for film lovers, as it is fascinating to watch Kubrick learning as the film continues. His exploration of the psyche of the American soldier is the heart and soul of this compelling black-and-white war drama that is worth seeing for more than just historical reasons. “There is a war in this forest. Not a war that has been fought, nor one that will be, but any war,” narrator David Allen explains at the beginning of the film. “And the enemies who struggle here do not exist unless we call them into being. This forest then, and all that happens now, is outside history. Only the unchanging shapes of fear and doubt and death are from our world. These soldiers that you see keep our language and our time but have no other country but the mind.” Fear and Desire lays the groundwork for much of what is to follow in Kubrick’s remarkable career.

The annual New Directors, New Films series, a joint presentation of MoMA and the Film Society of Lincoln Center, has been highlighting works by up-and-coming international directors for more than forty years. But the 2012 slate of films includes one intriguing surprise: Stanley Kubrick’s 1953 seldom-seen psychological war drama, Fear and Desire. Kubrick’s first full-length film, made when he was twenty-four, is a curious tale about four soldiers (Steve Coit, Kenneth Harp, Paul Mazursky, and Frank Silvera) trapped six miles behind enemy lines. When they are spotted by a local woman (Virginia Leith), they decide to capture her and tie her up, but leaving Sidney (Mazursky) behind to keep an eye on her turns out to be a bad idea. Meanwhile, they discover a nearby house that has been occupied by the enemy and argue over whether to attack or retreat. Written by Howard Sackler, who was a high school classmate of Kubrick’s in the Bronx and would later win the Pulitzer Prize for The Great White Hope, and directed, edited, and photographed by the man who would go on to make such war epics as Paths of Glory, Full Metal Jacket, and Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Fear and Desire features stilted dialogue, much of which is spoken off-camera and feels like it was dubbed in later. Many of the cuts are jumpy and much of the framing amateurish. Kubrick was ultimately disappointed with the film and wanted it pulled from circulation; instead it was preserved by Eastman House in 1989 and restored twenty years later, which is good news for film lovers, as it is fascinating to watch Kubrick learning as the film continues. His exploration of the psyche of the American soldier is the heart and soul of this compelling black-and-white war drama that is worth seeing for more than just historical reasons. “There is a war in this forest. Not a war that has been fought, nor one that will be, but any war,” narrator David Allen explains at the beginning of the film. “And the enemies who struggle here do not exist unless we call them into being. This forest then, and all that happens now, is outside history. Only the unchanging shapes of fear and doubt and death are from our world. These soldiers that you see keep our language and our time but have no other country but the mind.” Fear and Desire lays the groundwork for much of what is to follow in Kubrick’s remarkable career.