Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn is a poignant, poetic farewell to the cinema

GOODBYE, DRAGON INN (Tsai Ming-liang, 2003)

Metrograph (in-person and digital)

7 Ludlow St. between Canal & Hester Sts.

Thursday, December 21, 7:15

Thursday, December 28, 1:45

Saturday, December 30, 12:30

metrograph.com

Taiwanese master Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn is a heart-stirring elegy to going to the movies, returning to Metrograph screens after streaming in a gorgeous 4K restoration at Metrograph Digital in 2020. The accidentally prescient 2003 film takes place in central Taipei in and around the Fu-Ho Grand Theater, which is about to be torn down. For its finale, the Fu-Ho is screening King Hu’s 1967 wuxia classic Dragon Inn, Hu’s first work after moving from Hong Kong to Taiwan; the film is set in the Ming dynasty and involves assassins and eunuchs.

In 2021, Tsai’s film seems set in a long-ago time as well. It opens during a crowded showing of Dragon Inn in which Tsai’s longtime cinematographer, Liao Pen-jung, places the viewer in a seat in the theater, watching the film over and around two heads in front of their seat, one partially blocking the screen, which doesn’t happen when viewing a film on a smaller screen at home — especially during a pandemic, when no one was seeing any films in movie theaters. So Goodbye, Dragon Inn takes on a much bigger meaning, since the lockdown has changed how we experience movies forever.

Most of the film focuses on the last screening at the Fu-Ho, with only a handful of people in the audience: a jittery Japanese tourist (Mitamura Kiyonobu), a woman eating peanuts or seeds (Yang Kuei-mei), a young man in a leather jacket (Tsai regular Chen Chao-jung), a child, and two older men, played by Jun Shih and Miao Tien, who are actually the stars of the film being shown. (They portray Xiao Shao-zi and Pi Shao-tang, respectively, in Dragon Inn.) In one of the only scenes with dialogue, Miao says, “I haven’t seen a movie in a long time,” to which Chun responds, “No one goes to the movies anymore, and no one remembers us anymore.”

The tourist, a reminder of Japan’s occupation of Taiwan from 1895 to 1945, spends much of the movie trying to find a light for his cigarette — a homoerotic gesture — as well as a better seat, as he is constantly beset by people sitting right next to him or right behind him and putting their bare feet practically in his face or noisily crunching food, even though the large theater is nearly empty. In one of the film’s most darkly comic moments, two men line up on either side of him at a row of urinals, and then a third man comes in to reach over and grab the cigarettes he left on the shelf above where the tourist is urinating. Nobody says a word as Tsai lingers on the scene, the camera not moving. In fact, there is very little camera movement throughout the film; instead, long scenes play out in real time as in an Ozu film, in stark contrast to the action happening onscreen.

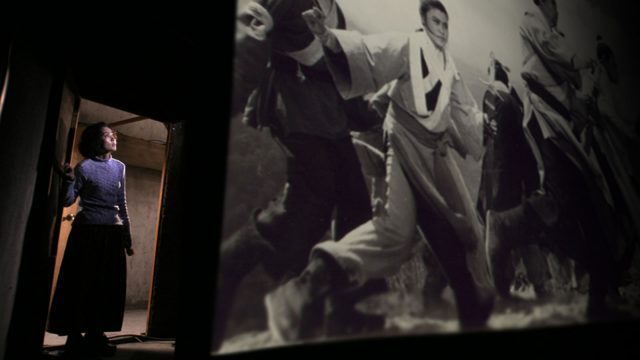

Meanwhile, the ticket woman (Chen Shiang-chyi), who has a disabled foot and a severe limp, cleans the bathroom, slowly steams and eats part of a bun, walks down a long hallway, and brings food to the projectionist (Tsai mainstay Lee Kang-sheng). She is steeped in an almost unbearable loneliness; she peeks in from behind a curtain to peer at the few patrons in the theater, and at one point she emerges from a door next to the screen, looking up as if she wishes to be part of the movie instead of the laborious life she’s living.

A woman (Chen Shiang-chyi) works during the final screening at the Fu-Ho Grand Theater in Goodbye, Dragon Inn

In his Metrograph Journal essay “Chasing the Film Spirit,” Tsai, whose other works include Rebels of the Neon God, The River, The Hole, Days, and What Time Is It There? — which has a scene set in the Fu-Ho, where he also held the premiere — writes, “My grandmother and grandfather were the biggest cinephiles I knew, and we started going to movies together when I was three years old. We would go to the cinema twice a day, every day. Sometimes we would watch the same film over and over again, and sometimes we would find different cinemas to watch something new. That was a golden age for cinema, and I’m proud my childhood coincided with that time.”

He continues, “Nowadays everyone watches movies on planes. On any given flight, no matter the airline, you can choose from hundreds of films: Hollywood, Bollywood, all different types of movies. However, you can count on one thing: You’ll never find a Tsai Ming-liang picture on a plane, as I make films that have to be seen on the big screen.” Unfortunately, in 2020-21, we had no choice but to watch Goodbye, Dragon Inn on small monitors, but now you can catch this must-see, stunningly paced elegiac love letter on the silver screen, sitting in a dark theater with dozens or hundreds of strangers, staring up at light being projected onto a screen at twenty-four frames per second, telling a story as only a movie can, with a head partially blocking your view, bare feet in your face, and someone crunching too loudly right behind.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]

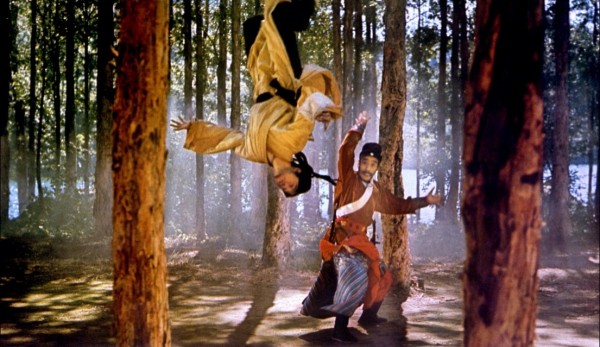

Watching King Hu’s 1969 wuxia classic, A Touch of Zen, brings us back to the days of couching out with Kung Fu Theater on rainy Saturday afternoons. The highly influential three-hour epic features an impossible-to-figure-out plot, a goofy romance, wicked-cool weaponry, an awesome Buddhist monk, a bloody massacre, and action scenes that clearly involve the overuse of trampolines. Still, it’s great fun, even if it is way too long. (The film, which was initially shown in two parts, earned a special technical prize at the 1975 Cannes Film Festival.) Shih Jun stars as Ku Shen Chai, a local calligrapher and scholar who is extremely curious when the mysterious Ouyang Nin (Tin Peng) suddenly show up in town. It turns out that Ouyang is after Miss Yang (Hsu Feng) to exact “justice” for the corrupt Eunuch Wei, who is out to kill her entire family. Hu (Come Drink with Me, Dragon Gate Inn) fills the film with long, poetic establishing shots of fields and the fort, using herky-jerky camera movements (that might or might not have been done on purpose) and throwing in an ultra-trippy psychedelic mountain scene that is about as 1960s as it gets. A Touch of Zen is ostensibly about Ku’s journey toward enlightenment, but it’s also about so much more, although we’re not completely sure what that is. The film is screening on October 5 at 9:00 as part of the fifty-third New York Film Festival’s Revivals sidebar, which continues through October 11 with

Watching King Hu’s 1969 wuxia classic, A Touch of Zen, brings us back to the days of couching out with Kung Fu Theater on rainy Saturday afternoons. The highly influential three-hour epic features an impossible-to-figure-out plot, a goofy romance, wicked-cool weaponry, an awesome Buddhist monk, a bloody massacre, and action scenes that clearly involve the overuse of trampolines. Still, it’s great fun, even if it is way too long. (The film, which was initially shown in two parts, earned a special technical prize at the 1975 Cannes Film Festival.) Shih Jun stars as Ku Shen Chai, a local calligrapher and scholar who is extremely curious when the mysterious Ouyang Nin (Tin Peng) suddenly show up in town. It turns out that Ouyang is after Miss Yang (Hsu Feng) to exact “justice” for the corrupt Eunuch Wei, who is out to kill her entire family. Hu (Come Drink with Me, Dragon Gate Inn) fills the film with long, poetic establishing shots of fields and the fort, using herky-jerky camera movements (that might or might not have been done on purpose) and throwing in an ultra-trippy psychedelic mountain scene that is about as 1960s as it gets. A Touch of Zen is ostensibly about Ku’s journey toward enlightenment, but it’s also about so much more, although we’re not completely sure what that is. The film is screening on October 5 at 9:00 as part of the fifty-third New York Film Festival’s Revivals sidebar, which continues through October 11 with