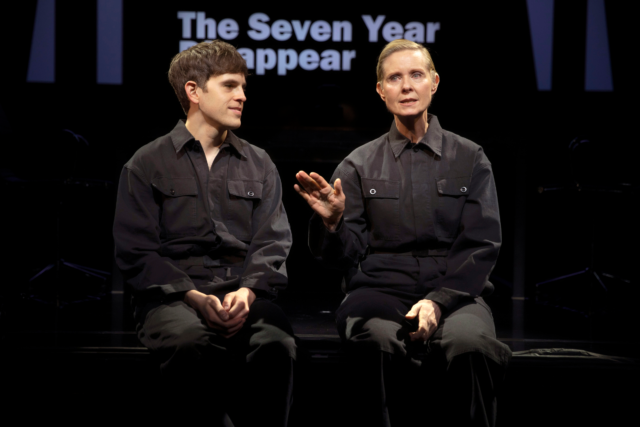

Chris Domig and Len Cariou star in touching revival of Tuesdays with Morrie (photo by Jeremy Varner)

TUESDAYS WITH MORRIE

St. George’s Episcopal Church

209 East Sixteenth St. at Rutherford Pl.

Through March 23, $20-$55

www.seadogtheater.org

“I never give advice,” Morrie Schwartz tells Mitch Albom in Tuesdays with Morrie.

Maybe not, but nearly everything that comes out of his mouth are words to live by — and die by.

Albom’s Tuesdays with Morrie, the true story of the friendship between sports reporter Albom and Brandeis professor Schwartz, started as a 1997 book, subtitled An Old Man, a Young Man, and Life’s Greatest Lesson. Mick Jackson turned it into a popular 1999 film, starring Jack Lemmon as Schwartz and Hank Azaria as Albom. It won four Emmys, including Outstanding Made for Television Movie, and put the memoir at the top of the bestseller list for a combined twenty-three weeks. In November 2002, Albom and Jeffrey Hatcher adapted the book into an off-Broadway play directed by Obie winner David Esbjornson.

The show is now back in a warm, intimate revival from Sea Dog Theater running in the long, narrow chantry at St. George’s Episcopal Church through March 23, anchored by two wonderful performances.

As the audience enters the space, Mitch (Chris Domig) is sitting behind a grand piano at the center of the room, playing jazz tunes. After a few songs, Morrie (Len Cariou) enters, joining Mitch on the piano bench and enjoying the music. The play proper soon begins, with Mitch directly addressing the audience, telling us about a college class he had taken with Morrie called “The Meaning of Life.” Mitch, the only student, remembers, “There was no required reading, but many topics were covered: love, work, aging, family, community, forgiveness . . . and death.” Those are the same topics covered in the play.

Mitch, who is thirty-seven, and Morrie, who is seventy-eight, switch back and forth between talking to the audience and reenacting scenes from their past together. Mitch took all of Morrie’s classes at Brandeis; the two became fast friends, with Mitch calling his mentor “Coach.” When Mitch graduates in 1979, he promises to keep in touch, but sixteen years pass with no contact, until he sees his old teacher on Nightline, explaining to Ted Koppel that he has ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease. Feeling guilty, Mitch goes to see Morrie; when his teacher asks him what happened, Mitch responds, “Life happened.”

What Mitch thought would be a one-time visit becomes a weekly event, and Mitch begins recording his Tuesday discussions with Morrie, who has found it somewhat surprising that people are so interested in him now. “I’m not quite alive, I’m not quite dead, I’m ‘in-between,’” he says. “I’m about to take that last journey into the great unknown. People want to know what to pack.”

Morrie might not ever give advice, but he speaks in memorable aphorisms that avoid being overly treacly:

“Dying is only one thing to be sad over. Living unhappily is something else.”

“Why be predictable?”

“Aging is not just decay . . . . A tree’s leaves are most colorful just before they die.”

“Age is not a competition.”

“There’s no ‘point’ in loving; loving is the point.”

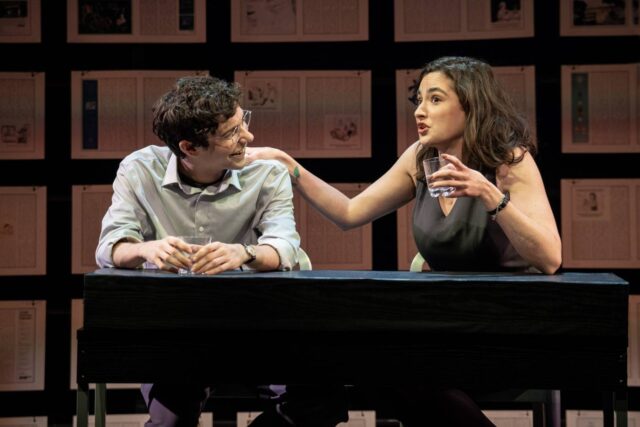

Mitch (Chris Domig) worries about his dying friend, Morrie (Len Cariou), in Tuesdays with Morrie (photo by Jeremy Varner)

The two men share stories from their lives, delving into career choices, music, romantic partners, parents, and children. Initially, Mitch is tentative and anxious, regularly on his phone as he prepares for his next column, interview, or television appearance. He does slow down a bit as Morrie grows more and more ill, the end approaching, which makes Mitch more sad than Morrie. Mitch might have told us early on, “I don’t need a ‘life therapist,’” but he is learning so much from Coach — and so are we.

Tuesdays with Morrie feels right at home in St. George’s, even as it features two Jewish characters; Guy DeLancey’s set and lighting center around the piano and cast glows on the pillars, and Eamon Goodman’s sound, from the dialogue to actor and composer Domig’s expert keyboard playing to a snippet of a pop standard, are never lost in the high-ceilinged room over the course of the play’s easygoing hundred minutes.

Tony winner and Emmy nominee Cariou (Sweeney Todd, A Little Night Music) is gentle and touching as Morrie; at eighty-four, Cariou has both the stage and the life experience, and it shows in his every gesture and turn of phrase. You can’t help but love being in his presence, as actor and character.

Domig, the cofounder of Sea Dog Theater, is terrific as the self-involved, super-ambitious Mitch, who has never stopped and smelled the roses. Domig is almost too nice; Morrie tells Mitch that he can be “mean-spirited,” something I noticed while watching Albom for several years on the Sunday morning ESPN program The Sports Reporters. Cariou and Domig also dodge around some of the more clichéd and melodramatic aspects of the script with the help of director Erwin Maas; the trio has spent a lot of time working together on the project, beginning with a reading at St. George’s in 2021, and they clearly have developed an infectious camaraderie.

“Are you at peace with yourself?” Morrie asks Mitch.

After seeing this adaptation of Tuesdays with Morrie, your answer will be a lot clearer.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]