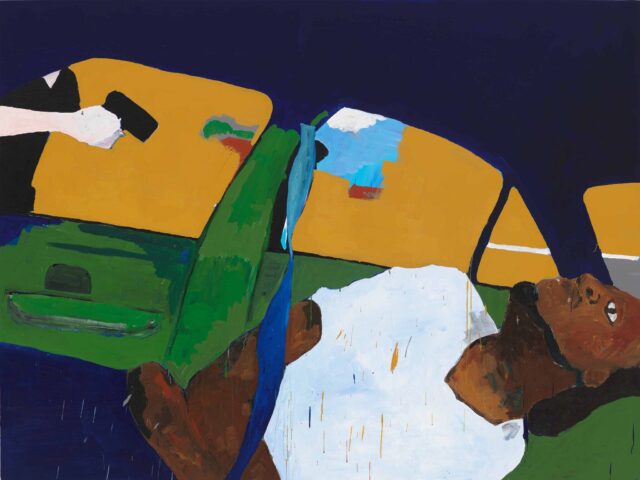

Henry Taylor, THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH!, acrylic on canvas, 2017 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from Jonathan Sobel & Marcia Dunn / © Henry Taylor)

HENRY TAYLOR: B SIDE

Whitney Museum of American Art

99 Gansevoort St.

Through January 28, $24-$30

212-570-3600

whitney.org

Among the many joys of the Whitney exhibit “Henry Taylor: B Side,” one of the best exhibitions of 2023 — catch it before it closes January 28 — is the audio guide. The work itself is extraordinary: stunning portraits, installations, assembled sculptures, early drawings, painted objects. Taylor, who was born in 1958 in Oxnard, California, and lives in Los Angeles, shares intimate details of his process on the guide, as do several subjects of his, artists themselves.

Regarding the above painting, a depiction of the murder of Philando Castile based on video taken by his girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, Taylor says, “It was definitely emotional. . . . I do have a habit. I was a journalism major. Articles and things permeate. And then you say, no,I don’t want to do it. So, you have this ambivalence. But it’s not like I’m grabbing certain headlines. Sometimes we become, sort of, nonchalant is not the word, but when something happens over and over, we become sort of immune to it. But I think I just really reacted, you know what I mean?”

Below are six more works, with highlights from the audio.

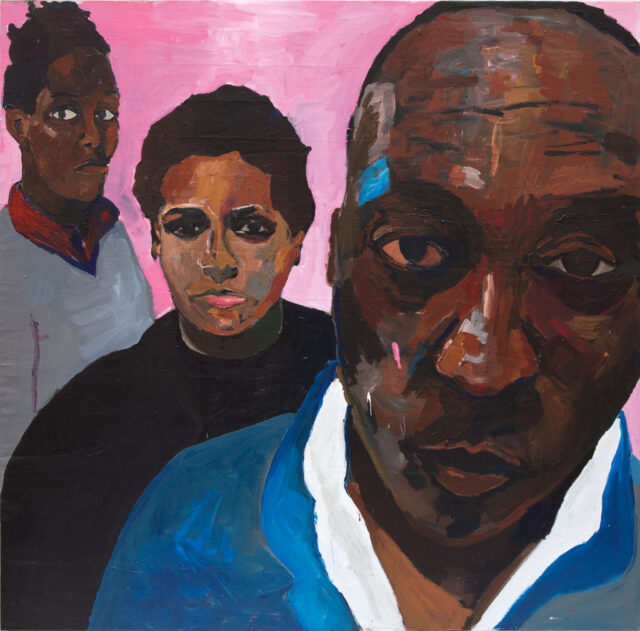

Henry Taylor, i’m yours, acrylic on canvas, 2015 (courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth / photo by Sam Kahn)

Henry Taylor: I don’t always work from photographs, but this was a photograph taken by Andrea Bowers, and I liked it. . . . In the original photograph was just my son and I. And I added my daughter. Sometimes I might have material in the studio that I just grab or gravitate to. Sometimes it’s just there for a long time. So, you just put it to use, so to speak.

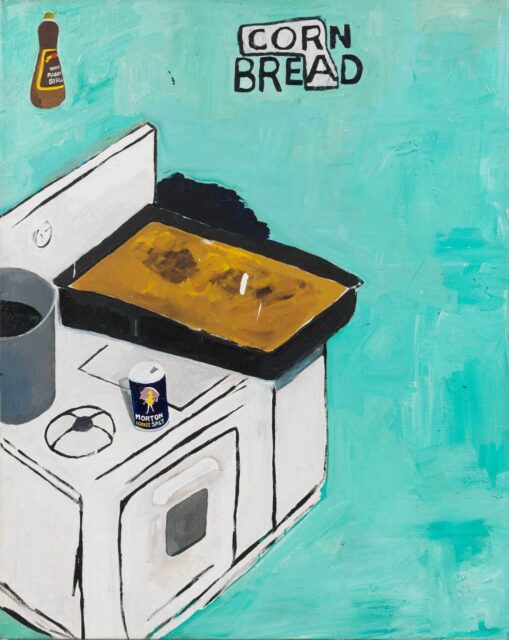

Henry Taylor, Cora (cornbread), acrylic on canvas, 2008 (courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth / © Henry Taylor; photo by Jeff McLane

Andrea Bowers: It’s a beautiful old stove. And when Henry was living in downtown Los Angeles, near Chinatown, he had this beautiful old stove, very similar to this, and he cooked constantly. And his meals were fantastic. And he always said that his mother taught him how to cook. And so, I love that he found her name, “Cora,” in the word “cornbread.” And I think this was always a painting that Henry always had hanging wherever he lived. Seemed to be really meaningful to him, like a really special painting. . . . I think that Henry has painted almost every day of his life. . . . When you start working with materials, there’s things that are going to come up, that’s a whole different kind of knowledge or communication. And I think that’s where Henry’s brilliance lies, just the day-to-day working. He loves to do it. And he paints all the time, and that’s beautiful.

Henry Taylor, Andrea Bowers, acrylic on canvas, 2010 (courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth / photo by Robert Bean)

Andrea Bowers: Henry and I are friends, so I was over there all the time. So it was like, “Okay, I’m going to sit here.” I don’t know, it was probably, like, probably five sessions or something, but for kind of long periods, he kept working on it. I’m sure everyone has told you that he makes really funny faces when he draws? Oh, okay. So, Henry’s really famous for that, the intensity that he gets on the face and the speed at which he’s looking and recording, looking, recording, looking and recording, with this kind of squint, and real intensity with one eye. And the other he’s squinting with. So that’s really fun, because he’s so in it, and he’s so focused. And you can see it. You’re just constantly aware of being recorded, This is real work he’s doing. It’s really interesting and fun.

Installation view of “Henry Taylor: B Side,“ including Y’ALL STARTED THIS SHIT ANYWAY, mixed media, 2021 (photo by Ron Amstutz)

Henry Taylor: You hear writers who talk about, oh, I wrote that song in twenty minutes, and it was a hit. This one just came together. And it seemed to have a nice compact little story — for me anyway. There’s a head, a decapitated . . . or just a mannequin’s head. And maybe I was thinking of just putting everything together or some of the materials like, oh, I had a bull. I have the head. I’m thinking about Native Americans. I’m thinking about green pastures and I’m thinking about golf, and I’m thinking about land and you know the white golf thing. I just thought that the buffalo and everything just kind of worked for me. And the cowboy boots, you know, that kind of goes. The buffalo, the boots. Buffalo Bill. Hey!

Henry Taylor: My brother was about five years older than me, four grades, when I was in the ninth he was in twelfth. So, he made me aware of things like Bobby Seale, Eldridge Cleaver, George Jackson. And so, I was thinking about a leather jacket. I had an idea to make only one jacket. But huge, because I didn’t know anything about this space [at LACMA]. But I was given another space. So, I was experimenting, say like closet-size. So, maybe I had eight jackets. So, it just took off from there. And I thought about the [January 6] insurrection. That is scary to me. But I don’t think — the Panthers weren’t trying to be intimidating. This was trying to save people.

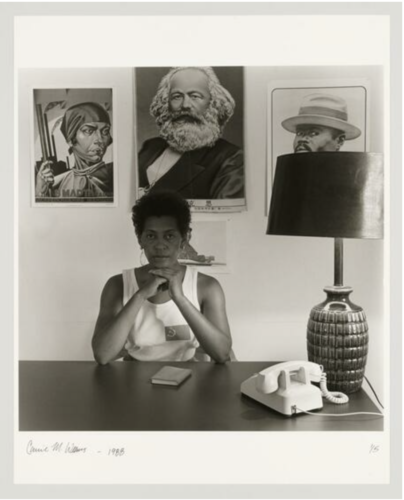

Henry Taylor, Deana Lawson in the Lionel Hamptons, acrylic on canvas, 2013 (courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth / photo by Sam Kahn)

Henry Taylor: Deana [Lawson] is a photographer, a really good one, and a dear friend. And I was fortunate enough to go to Haiti with her and watch her in action. I guess this is something I did when I was visiting A. C. Hudgins, who was a collector out in the Hamptons. But, and that’s what we’d do out there, or I would do out there. I’d always have canvas there. I think I’m one of those people that just travels with material and likes to engage with nature and with people. And musicians often carry their guitar and play and collaborate and so, I look at it like that. It’s just something I enjoy doing. I love to paint.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]