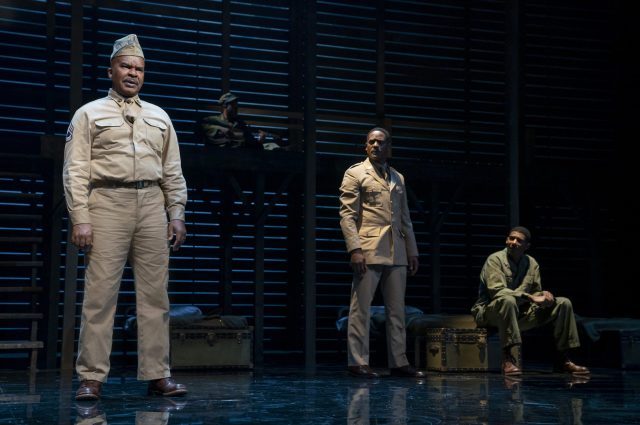

Capt. Richard Davenport (Blair Underwood) and Pvt. James Wilkie (Billy Eugene Jones) watch Sgt. Vernon C. Waters (David Alan Grier) in flashback in A Soldier’s Play (photo by Joan Marcus)

American Airlines Theatre

227 West 42nd St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through March 15, $59-$299

212-719-1300

www.roundabouttheatre.org

Perhaps no one knows Charles Fuller’s A Soldier’s Play better than David Alan Grier, even more so than Fuller himself. In the show’s original 1981-83 Negro Ensemble run, which earned Fuller the Pulitzer Prize and featured Adolph Caesar, Denzel Washington, and Samuel L. Jackson, Grier replaced Larry Riley as Pvt. C. J. Memphis. In Norman Jewison’s 1984 film, starring Caesar, Washington, Riley, Howard E. Rollins Jr., Wings Hauser, Robert Townsend, and Patti LaBelle, Grier played Cpl. Bernard Cobb. And now Grier is taking on the role of controversial sergeant Vernon C. Waters in the show’s Broadway debut, a Roundabout production that moves with expert military precision at the American Airlines Theatre.

It’s 1944, and Waters is in charge of an all-black unit of the 221st Chemical Smoke Generating Company at Fort Neal, Louisiana, under the command of Capt. Charles Taylor (Jerry O’Connell). In the opening moment, a drunk Waters is on his knees on a platform, calling out, “They’ll still hate you!” A shot rings out, and Waters falls dead, murdered in cold blood by an unseen perpetrator. Capt. Richard Davenport (Blair Underwood), a black lawyer attached to the 343rd Military Police Corps Unit, arrives to solve the crime, but the white Taylor has a problem with that.

“I didn’t know that Major Hines was assigning a Negro, Davenport,” Taylor says. “My preparations were made in the belief that you’d be a white man. I think it only fair to tell you that had I known what Hines intended I would have requested the immediate suspension of the investigation. . . . I don’t want to offend you, but I just cannot get used to it — the bars, the uniform — being in charge just doesn’t look right on Negroes!” Taylor attempts to talk Davenport out of accepting the case, in part because of the danger he thinks he will face from the local KKK, but Davenport is not about to be scared into leaving. “I got it. And I am in charge! All your orders instruct you to do is cooperate!” he firmly declares.

Capt. Charles Taylor (Jerry O’Connell) is not thrilled that Capt. Richard Davenport (Blair Underwood) has come to investigate a murder in Roundabout Broadway production (photo by Joan Marcus)

Assisted by Taylor’s right-hand man, Cpl. Ellis (Warner Miller), Davenport begins interrogating the members of the unit, which includes Pfc Melvin Peterson (Nnamdi Asomugha), Pvt. Louis Henson (McKinley Belcher III), Cpl. Cobb (Rob Demery), Pvt. Tony Smalls (Jared Grimes), Pvt. James Wilkie (Billy Eugene Jones), and Pvt. Memphis (J. Alphonse Nicholson), each of whom had a unique relationship with Waters, via their responsibilities to the army as well as through their place on the company’s extremely successful baseball team, as most of them played in the Negro League. Their stories unfold in flashback as Davenport and the witness sit stage right as the captain watches the action take place in the center and at left. Derek McLane’s two-level wooden set switches from the men’s barracks to Davenport’s and Taylor’s offices as chairs and desks are brought on and offstage and beds are pushed from the back to the front, accompanied by sharp lighting by Allen Lee Hughes.

Davenport also speaks with key white suspects Lt. Byrd (Nate Mann) and Capt. Wilcox (Lee Aaron Rosen); the former in particular is an avowed racist with no respect for Davenport. “Where I come from, colored don’t talk the way he spoke to us — not to white people they don’t!” Byrd says about Waters, talking about the night of the killing. Davenport discovers that Waters apparently had many more enemies than friends, resulting in plenty of suspects.

Broadway debut of Charles Fuller’s A Soldier’s Play is set in an all-black army barracks during WWII (photo by Joan Marcus)

Directed with adroit sureness by Tony winner Kenny Leon (A Raisin in the Sun, American Son) and loosely inspired by Herman Melville’s 1924 novella Billy Budd, A Soldier’s Play is a scorching look at racism, in the military in 1944 as well as today. Waters strongly believes that black men need to rethink their place in society and how they will succeed. “The First War, it didn’t change much for us, boy — but this one — it’s gonna change a lot of things,” he tells Memphis. “The black race can’t afford you no more. There use ta be a time when we’d see somebody like you, singin’, clownin’ — yas-sah-bossin’ — and we wouldn’t do anything. . . . Not no more. The day of the geechy is gone, boy — the only thing that can move the race is power. It’s all the white respects — and people like you just make us seem like fools.” It’s not a position that everyone agrees with, but Grier (Porgy and Bess, In Living Color) handles the role with a grace and intelligence that makes Waters neither hero nor villain, instead a strong-willed individual with a different experience than his fellow soldiers, and a different way of approaching the future.

Underwood (A Streetcar Named Desire, The Trip to Bountiful), whose father is a retired army colonel, is bold and steadfast as Davenport, a fearless man who is going to stand by his convictions and fight for what he’s earned. O’Connell (Stand by Me, Seminar) is resolute as Taylor, who is somewhat caught in the middle, a stand-in for much of America of the 1940s (and today), wrestling with the racism he grew up with while seemingly trying to accept that things are changing. Leon and Fuller (Zooman and the Sign, A Gathering of Old Men) do an excellent job developing the characters, each actor — there are no women in this testosterone-filled tale — getting the chance to speak his mind, wearing Dede Ayite’s effective costumes and eliciting some whoops when taking them off. Now almost forty years old, A Soldier’s Play doesn’t feel dated in the least. In fact, it feels all too of-the-moment, and all too necessary.