Jess Thom’s multidimensional Not I is a stirring evening of communal theater (photo by James Lyndsay)

BRIC House Ballroom

January 10 – January 19, $30

647 Fulton St.

publictheater.org

www.bricartsmedia.org

London-born comedian and disability activist Jess Thom returns to the BRIC House Ballroom with a spectacular sixty-minute presentation, a brilliantly conceived evening that reimagines the theatrical experience, for both actor and audience. In May 2016, Thom, who has Tourette Syndrome, held the New York premiere of her Edinburgh Fringe hit Backstage in Biscuit Land at the Brooklyn arts institution, delivering a “one-woman show for two” that humorously looks at her life and how she deals with Tourette’s, a neurological disorder that causes her to uncontrollably shout out words and phrases, such as “biscuit,” “hedgehog,” “sausage,” “I love cats,” and “Fuck a goat.” (Only ten percent of those with Tourette’s have copralalia, involving foul language.) She also uses a wheelchair, as her disability comprises various physical tics, such as banging her chest whenever she says “biscuit,” that make it too dangerous for her to walk on her feet.

Back at BRIC for the Public Theater’s Under the Radar Festival, Thom is performing Samuel Beckett’s 1972 monologue Not I in a relaxed, inclusive environment. As you enter the small, intimate black-box space, Thom is in her wheelchair, greeting each audience member and inviting them to sit either on cushions, benches, or folding chairs. She is friendly and outgoing, and she doesn’t pause or change moods when the tics come up. She even plays off them; for example, when she says, “I love cats,” she quickly adds something like, “Well, I don’t really even like cats,” and when she proclaims, “Fuck a goat,” she responds by assuring everyone that no one will be having sex with an animal. Meanwhile, to her right, ASL performer Lindsey D. Snyder signs everything Thom says, including the verbal tics. Reaching the whole audience matters to Thom: The seating in Not I is inspired by how she was rudely treated when she attended a 2011 show by stand-up comic Mark Thomas, when theater staff confined her to a sound booth because other members of the audience objected to her gesticulations and vocal outbursts.

Once everyone is settled, she explains the plans for the evening and describes how a friend had told her that she should consider staging her own version of Not I, because it relates so organically to her life. The play, which has been performed by such actresses as Jessica Tandy, Beckett muse Billie Whitelaw, Julianne Moore, and Lisa Dwan and gets its title because it is told in the third person by the protagonist, is an ellipses-filled diatribe of incomplete thoughts and tangents that generally runs between nine and fifteen minutes; it is not a race, but the performer is expected to go through the 2,268 words as fast as possible. “I am not unduly concerned with intelligibility. I hope the piece may work on the nerves of the audience, not its intellect,” Beckett wrote in a 1972 letter to Tandy prior to the play’s world premiere at Lincoln Center. Dressed all in black, wearing a balaclava and a hoodie, Thom, in her wheelchair, is lifted eight feet in the air (the set is designed by Ben Pacey), and she is lit so only the bottom half of her face can be seen. Usually, only the actress’s mouth can be seen, as if it exists by itself, but changes had to be made because of Thom’s Tourette’s. As she power-drives through the piece, she occasionally gets caught in a series of “biscuit” moments but then forges ahead. She is moving through the dialogue so fast, and so unpredictably, that Snyder, also dressed in black and taking the place of the Auditor, the second character in the play, is practically dancing on the floor. (Beckett’s movement directions for the Auditor note, “This consists in simple sideways raising of arms from sides and their falling back, in a gesture of helpless compassion.”)

The audience is not meant to understand every word and plot detail as a woman, identified as “Mouth” in the script, relates several stories involving shopping in a supermarket, going to court, sitting on a mound in Croker’s Acres, and searching for cowslips in a field, bringing up such concepts as shame, torment, sin, pleasure, and guilt. This protagonist has suffered an unnamed trauma that has led to her becoming an outcast from society and virtually unable to communicate with others via speech. It’s clear why Thom’s friend suggested Not I for her, perhaps most evident from the following excerpt:

“what? . . tongue? . . yes . . . lips . . . cheeks . . . jaws . . . tongue . . . never still a second . . . mouth on fire . . . stream of words . . . in her ear . . . practically in her ear . . . not catching the half . . . not the quarter . . . no idea what she’s saying . . . imagine! . . no idea what she’s saying! . . and can’t stop . . . no stopping it . . . she who but a moment before . . . but a moment! . . could not make a sound . . . no sound of any kind . . . now can’t stop . . . imagine! . . can’t stop the stream . . . and the whole brain begging . . . something begging in the brain . . . begging the mouth to stop . . . pause a moment . . . if only for a moment . . . and no response . . . as if it hadn’t heard . . . or couldn’t . . . couldn’t pause a second . . . like maddened . . . all that together . . . straining to hear . . . piece it together . . . and the brain . . . raving away on its own . . . trying to make sense of it . . . or make it stop . . .”

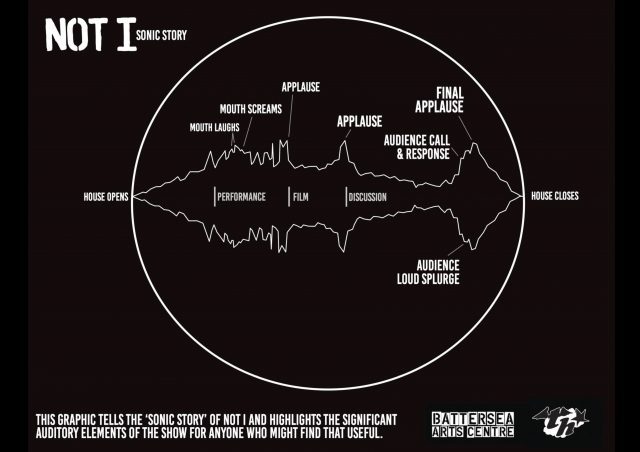

Not I has a sound map to ensure everyone is comfortable and no one feels excluded for auditory reasons

When we go to live theater and watch someone stumble over lines or hesitate and stammer as if they’ve lost their place, our hearts tend to sink and we don’t want the actor to be embarrassed. But when Thom, tearing through the words at a frenetic pace, suddenly goes into “biscuit” mode, not only are we rooting for her, we are with her every second, willing her on to get to the finish line with glory. It’s exhilarating when she storms back into Beckett’s language. But it’s important to note that we are not rooting for her because of or in spite of her disability (a word, by the way, that she freely uses); we are helping carry her to the end in a communal act that goes far beyond mere kindness.

The Beckett section is followed by Sophie Robinson’s short documentary Me, My Mouth, and I, which goes behind the scenes of the creation of Thom’s performance, and then Thom — who is also known as Touretteshero for her work with children and for her same-named organization that seeks to “change the world one tic at a time” — offers the audience the chance to talk to their neighbors about their thoughts on the play and ask her questions. The evening, which is passionately directed by her longtime collaborator Matthew Pountney, concludes with Thom signing copies of her 2012 book, Welcome to Biscuitland, in which Stephen Fry writes in the foreword, “Jess is a true hero, with or without her Touretteshero costume. Jess fuck biscuit Thom, I biscuit fuck fuck biscuit salute biscuit you.” And so will you.