Faye Driscoll’s Thank You for Coming: Space is making its NYC premiere at Live Artery festival (photo by Maria Baranova)

LIVE ARTERY

New York Live Arts

219 West 19th St.

January 8-11, $15-$30

Festival continues through January 15

newyorklivearts.org

fayedriscoll.com

Faye Driscoll concludes her seven-year “Thank You for Coming” trilogy with Space, a bold and courageous solo work making its New York City debut at New York Live Arts’ Live Artery winter performance festival this week. In March 2014’s Thank You for Coming: Attendance at Danspace, audience members could be as involved as they wanted to be as five dancers merged into one and Driscoll deconstructed and reconstructed the set as well as the relationship between performer and viewer. In November 2016’s Thank You for Coming: Play at BAM, Driscoll channeled passion, rage, intimacy, and an exhilarating frolicsomeness with five dancers and surprise appearances.

Inspired by the death of her mother, Space is about the physical and metaphysical weight we all carry every day as we attempt to shape our lives in a world that is whirling out of our control. The audience enters a blaringly white space on the stage, sitting in two rows of folding chairs; Nick Vaughan and Jake Margolin’s set evokes a waiting room between life and rebirth, a kind of bardo.

Faye Driscoll’s Thank You for Coming: Space concludes seven-year artistic journey between audience and performer (photo by Maria Baranova)

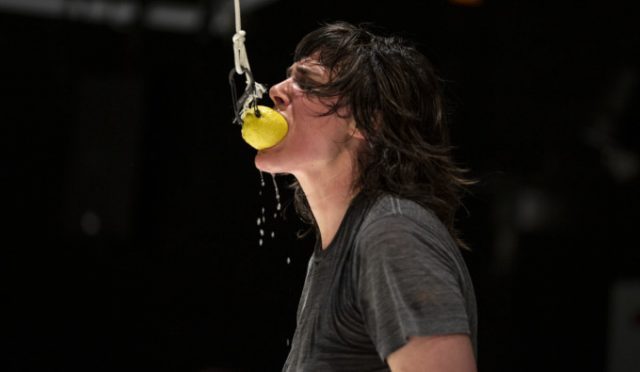

In each corner is a small platform, and various objects lie on the floor or hanging from the rafters, including small, triangular black sandbags, numerous microphones, boots, cinder blocks, and a lemon. Driscoll, a California native based in Brooklyn, enters the room on a warm, unpretentious note, thanking us for taking time out of our busy schedules to get out of bed, put on clothes, and come to the theater to see her. She moves to the center and sends a rusty, soundless bell into motion, circling around us but not quite hitting anyone, then slowing down like a pendulum, as if we are all running out of time. Over the next seventy-five minutes, Driscoll, barefoot, wearing black jeans and a gray T-shirt, records gasps, sighs, and roars into microphones, stomps around in boots connected to speakers, and lifts cinder blocks. She makes specific requests of the audience to perform an array of critical tasks, from raising and lowering objects via a pulley system to holding her hands to maintain her balance; each interaction with animate or inanimate objects results in Driscoll experimenting with new dance movements, merging reality and performance with relentlessly building intensity.

When she throws clumps of clay, it is as if she is demonstrating that we have only so much control over our life and our bodies and might just have to abandon ourselves to chaos. In fact, elements of the piece itself are unpredictable; the night I went, one of the objects got caught in the lighting above, forcing Driscoll (There Is So Much Mad in Me, You’re Me) to improvise, although there is a looseness as well that allowed her to discuss the situation briefly with one of the tech people. (Kudos must go out to sound engineer Zachary Crumrine, sound designer Andrew Gilbert, and text adviser Amanda K. Davidson, who keep us fully immersed and on our toes in the participatory piece.)

“Space confronts what is simultaneously the most certain and uncertain of human states, our undoing and our final flourishing,” Driscoll explains in the program, which also notes that the work was in process during the death of her mother. “It is a reckoning with the fact that one being’s transition from the state of the living calls forth a concurrent transition in those not dead.” Space ultimately transforms into a darkly funny meditation on death in a strange monologue by Driscoll, who is dripping wet with sweat. Her performance is fierce and ferocious, intimate and heart-rending; she holds nothing back, leaving the audience exhilarated and uncomfortable, frightful and concerned, yet oddly victorious. By the time it’s over, she has engaged four of our five senses (only Driscoll gets to taste) while referring not only to the end of life but of the show we’ve just experienced, as well as the trilogy itself. But rebirth awaits; the audience gets up and goes on with their lives, and Driscoll will go on with hers, including bringing Space to the Walker Art Center in March and the Wexner Center in April.