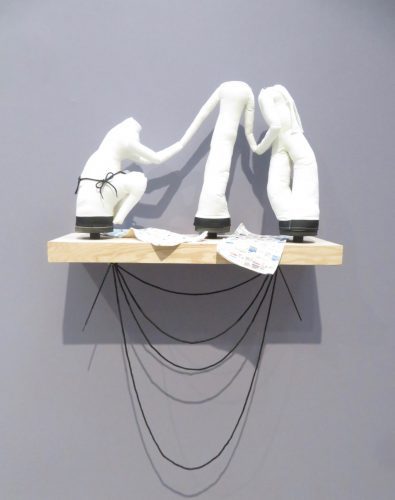

Paul Chan, Khara En Tria (Joyer in 3), nylon, fans, vinyl, polyfil, 2019 (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Greene Naftali Gallery

508 West 26th St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

Through October 19, free

www.greenenaftaligallery.com

Hong Kong-born, Nebraska-raised artist Paul Chan uses inflatable air dancers to reference art-historical themes and offer his take on the sorry state of the world in “The Bather’s Dilemma,” continuing at Greene Naftali through October 19. Chan, whose video installations include The 7 Lights, in which animated versions of people and debris fall from above, has created a series of beach tableaux in which the air dancers, generally seen as happy synthetic beings flailing about playfully, are weighed down, stuck, facing the problems tearing us apart despite their often bright color schemes. “At every age, overwhelming structural iniquities bring meaningless and arbitrary suffering and pain,” Chan writes in his “Sex, Water, Salvation, or What Is a Bather?” essay for the “Artistic License: Six Takes on the Guggenheim Collection” show on view at the Museum Mile institution through January 12. “And at every age, people organize to resist the best they can to try to stop the calamities from claiming more lives. Progress here means the collective power to stop ourselves from what we are most in danger of becoming. But progress takes a toll, especially on those who want it most. Resistance wears down the spirit, and makes a mess of the body and mind. It is a shame that it feels natural to expect suffering in oneself for the sake of ending it in others, and commonplace to accept this terrible symmetry as the price one pays for progress.”

Paul Chan, detail, La Baigneur 7 (Teenyelemachus), nylon, fan, dye paint on nylon, shoes, concrete, suicide cords, 2018 (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

At Greene Naftali, works such as Khara En Tria (Joyer in 3), 2chained or Genesia and Nemesia, Phenus 1, and La Baigneur 7 (Teenyelemachus) employ specially placed fans to make the figures move in specific patterns with one another, rather than randomly as air dancers usually do. Towels serve as counterweights and also are hung on the walls like canvases. The works recall paintings by Cézanne, Munch, and Renoir but are not celebrations in the sand. Chan continues, “The bather in art breaks with this terrible symmetry by offering an image of another way forward. Works that take up this motif invite us to reflect on how pleasure renews us. They are reminders that pleasing and being pleased – without aggression or guilt – expands our capacity for fellow feeling. Genuine pleasure is rejuvenating. And like that perfect night of sleep, it has a clarifying quality, as if one has emerged from a kind of cleansing. This sense of being cleansed is stimulating and healing, insofar as it helps renew us to more ably face what the day demands.” However, he makes clear: “Progress without pleasure at heart is not progress at all. But pleasure without progress in mind is destructive, deadening, or a bore.”

Paul Chan, Untitled (Katabasis with suspensions), muslin, nylon, polyfil, wire, wood, rope, inkjet on cotton, 2019 (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Poordysseus is an upside-down bather trapped in a vitrine. The hunched-over, black La Baigneur 7 (Teenyelemachus) includes what Chan calls “suicide cords,” electrical wiring plugged into shoes. The blue Bropheus wears a shirt that says, “Iche Hab Diche Lieb, Mann” (“I love you, man”), and he is situated on a beach towel made of opioid labels and an American flag color scheme. In the back room, smaller models stand on wooden platforms on the wall, studio detritus hanging below. The beach is supposed to be a place of beauty, a respite from the intense pressure of daily life, an opportunity to commune with nature, and one’s fellow human beings, in a carefree manner, despite the possibility of jellyfish and sharks in the water. But Chan also sees at least some hope in “The Bather’s Dilemma”; in the abovementioned essay, he is writing about the Guggenheim show but it also relates to his Greene Naftali exhibit: “Consider the following artworks as spirited invitations that encourage us to recall how enlivening it is to be near or in a river, some lake, or the open sea — and maybe a figure or two, naked or clothed, alone or no, to remember all that has been lost, how close it all is to disappearing, and what it takes to go on.”