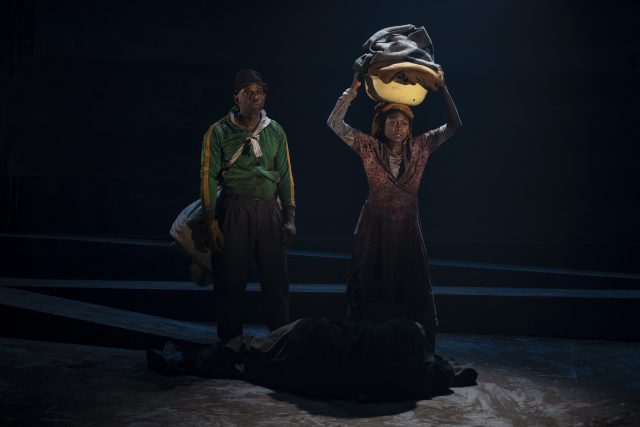

Boesman (Sahr Ngaujah) and Lena (Zainab Jah) arrive in the middle of nowhere in stark Fugard revival at the Signature (photo by Joan Marcus)

The Pershing Square Signature Center

The Alice Griffin Jewel Box Theatre

480 West 42nd St. between between Ninth & Tenth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through March 17, $35

www.signaturetheatre.org

For its fiftieth anniversary, South African playwright and director Yaël Farber reimagines Athol Fugard’s 1969 Boesman and Lena as an anti-Apartheid Waiting for Godot at the Signature, where it opens tonight and continues through March 17. Coincidentally, Farber’s fierce adaptation of Mies Julie, which transports August Strindberg’s Miss Julie to South Africa in 2012, is being performed at Classic Stage through March 10. At the Signature, the audience enters the Alice Griffin Jewel Box, where a large translucent plastic tarp flutters across the front of the stage like a sad, empty flag, blocking most of the set from view, except for the people in the center of the first row, who have to go under it to sit down. Boesman (Sahr Ngaujah) and Lena (Zainab Jah) come in through the aisles, laden with heavy bags that look like garbage, carrying their physical and metaphorical burdens with them. They are homeless, looking for a place to rest their weary, worn-out bodies. Boesman tears down the tarp, revealing a barren landscape in the middle of nowhere, the mud flats of the Swartkops River, save for one bare tree, echoing Samuel Beckett’s Godot. Susan Hilferty’s dark, drab set creates just the right atmosphere of dread; Hilferty also designed the appropriately ratty costumes for the play, which was inspired by an actual incident that Fugard experienced in 1965.

“Why did you walk so hard? In a hurry to get here? Jesus, Boesman! What’s here?” Lena asks as Boesman sets up a makeshift camp in the liminal space. “Look at us! Boesman and Lena with the sky for a roof again. What you waiting for?” While he tries to set up a place for them to sleep using the tarp and the tree, she rambles on about the sad circumstances of their life, which annoys him to no end. “‘When she puts down her bundle, she’ll start her rubbish.’ You did,” he says. “Rubbish?” she asks. “That long turd of nonsense that comes out when you open your mouth!” he replies. They bicker like George and Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, although she does most of the complaining. Lena: “This is a lonely place. Just us two. Talk to me.” Boesman: “I’ve got nothing left to say to you. Talk to yourself.” Lena: “I’ll go mad.” Boesman: “What do you mean ‘go’ mad?” But behind it all is the unspoken state of the nation, a South Africa mired in racism, where the white minority brutally rules over the dispossessed black majority.

Boesman (Sahr Ngaujah) mock-threatens Lena (Zainab Jah) as the Old African (Thomas Silcott) sits quietly in Boesman and Lena (photo by Joan Marcus)

A third person arrives, a slow-moving, raggedy Old African (Thomas Silcott) who mumbles in his tribal Xhosa language, which neither Boesman nor Lena understands. (The script translates his dialogue; he essentially explains that he is looking for his relatives but got lost.) Boesman is not about to share what little they have with the old man, or Outa, as Boesman calls him (he also refers to him with the offensive slang term “kaffir”), but Lena has sympathy for his situation. “To hell! He doesn’t belong to us,” Boesman cries out. “There was plenty of times his sort gave us water on the road,” Lena says. The couple keep up their war of words, arguing about happiness, geography, names, and dogs as they soldier on with what little they have. Lena also shows the Old African the bruises she has from where Boesman hits her. “And now? What’s going to happen now?” Boesman asks. “Is something going to happen now?” Lena responds. It’s both a pure Beckett moment as well as a commentary on how their miserable lives, and the lives of all the black and brown people of South Africa, are not about to change for the better any time soon.

Three lost souls try to escape the darkness of their world in Signature revival (photo by Joan Marcus)

Ngaujah (Mlima’s Tale, Fugard’s The Painted Rocks at Revolver Creek at the Signature) and Jah (School Girls; or, the African Mean Girls Play, Eclipsed) fully embody the desperation of their characters, a pair of lost souls with nowhere to go. The roles have previously been played onstage by Keith David and Lynne Thigpen in 1992 at City Center, on film by Danny Glover and Angela Bassett in 2000, and, in the original 1969 South African theatrical production, by Fugard and Yvonne Bryceland, both of whom are white; Glynn Day, who is also white, portrayed the Old African, reportedly in blackface. Silcott (Fugard’s Coming Home; Bring in ’Da Noise, Bring in ’Da Funk) is unrecognizable as the old man, beaten down to the point where he is practically invisible, fading into the darkness.

By having the characters wander through the aisles several times, Farber (Salomé, Amajuba: Like Doves We Rise) is implicating each one of us in their futility, as if Boesman and Lena are homeless and searching for a warm bed in an overcrowded New York City or refugees seeking a new life in an America that no longer welcomes them with open arms. Boesman treats the Old African much the same way. While there is hope and optimism in Godot, which has more than its fair share of comedic moments, the future is bleak for Boesman and Lena. “Now’s the time to laugh. This is also funny. Look at us!” Lena says, but their meager existence is no joke. This is the sixth Fugard play the Signature has produced as part of his ongoing residency since the company moved to its current building in 2012, including Blood Knot, The Train Driver, and Master Harold . . . and the Boys, and all those involved, from the cast and crew to the audience, have clearly benefited from so much time spent with Fugard.