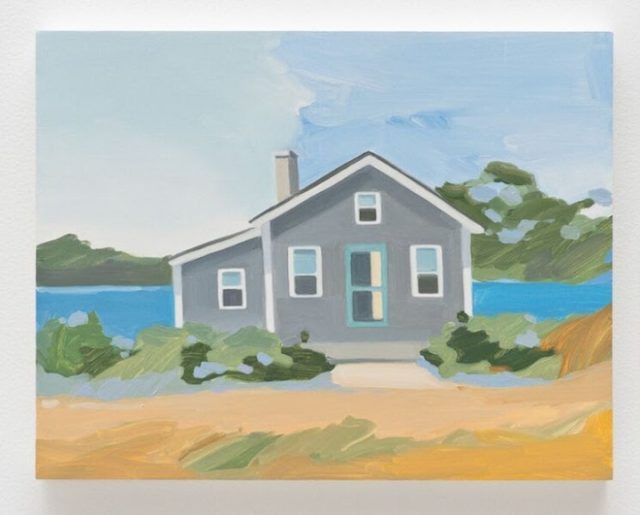

Maureen Gallace, “Beach Shack, Door,” oil on panel, 2015 (courtesy 303 Gallery)

MoMA PS1

22-25 Jackson Ave. at 46th Ave.

Thursday – Monday through September 10, suggested donation $5-$10 (free for New York City residents), 12 noon – 6:00 pm

718-784-2084

www.moma.org

For more than twenty-five years, painter Maureen Gallace has let her work do her talking for her. The Stamford-born, New York-based artist gives very few interviews, and the only monograph about her seems to be a thirty-two-page accompaniment to a small 2004 gallery show, with text by Rick Moody, who was born in New York City but also grew up primarily in Connecticut. For Gallace’s first major survey, the gorgeous “Clear Day,” continuing at MoMA PS1 through September 10, MoMA has provided very only the most basic of information; there is no catalog, no extensive wall or label text, and very spare press materials about the nearly seventy works. But that goes hand in hand with the wonderful aura and mystery that surround her small canvases, mostly exquisitely rendered paintings of homes on Cape Cod, each much more than it first appears. In 2016, as part of the Met’s “Artist Project,” Gallace made a short video discussing the still lifes of Paul Cézanne, concentrating on his paintings of apples. It’s a fascinating analysis of the painter and the painting; in fact, change just a few words here and there and Gallace could have just as easily been referring to her own creative process and output.

Maureen Gallace, “Surf Road,” oil on panel, 2015 (courtesy 303 Gallery)

“[Cézanne] was taking this simple, naïve everyday object that we’re all familiar with, but the paintings don’t ever feel about copying the apples. The paintings are about painting; you can see the canvas. Everything points back at what it took to make the painting,” she says over shots of some of Cézanne’s works. “Every single mark is laid bare, so he really wanted everybody to know the experience of the painter, and he took forever to make the paintings. . . . I’m someone who often takes an hour to make a brushmark; painting is a lot of thinking, a lot of staring. The emotion comes from the way paint is handled. The forms seem kind of crude because they’re built up from the marks. They’re so solid, the apples, they almost become sculpture. It’s like you could feel those apples in your hand. . . . There is an uneasiness to these paintings, and I think that comes from the shifting perspective. There’s no horizon line . . . and the tilting can be a little claustrophobic and destabilizing. There’s perfectionism in there; it’s so Type B, controlled, but also, it wasn’t about the one painting that was going to be the masterpiece. I mean, I think that was the point, to keep going, keep going, keep going and getting better and better and better, and so it was okay to fail. There’s less pressure on the painting because you’ll just get it right the next time. I think he was trying to put everything that he knew about painting into each object. . . . It’s a type of experience that some painters have; they need to distill things down to get at the essence of what painting is, even if it’s just choosing an apple.”

Maureen Gallace, “Clear Day,” oil on panel, 2012 (courtesy 303 Gallery)

In Gallace’s case, the apples have been replaced by cottages along the water on the Cape. Each house is different, but nearly every structure is not quite a true representation of reality, with compelling flourishes of abstraction. Gallace, who works from sketches and photographs rather than en plein air, often leaves out doors and windows, or paints roads that twist in impossible ways, or depicts a house that seems to be built right on top of the water. There are no interiors; in some works, you can see right through windows and across the ocean, as if there is no furniture inside, and there are no people anywhere. Gallace’s use of line, light, and color is breathtaking, much more complex than one might initially notice. The horizontal and angled lines of “Cape Cod, Winter” make the work resemble a Dali-esque faceless double portrait. The blue and white of the structure in “Blue Beach Shack” nearly disappears into the blue and white of the sky. Lush greenery surrounds a gray house in “September 1.” “Surf Road” consists of a patch of flowers in the left foreground, a windowless white and gray barn in the right background, and a deserted roadway through the middle, a pair of telephone poles standing like ghosts, with no wires connecting them to anything. There are no cars to be seen on “Merritt Parkway, Winter,” one of Connecticut’s busiest thoroughfares, a curious overpass awaiting in the distance. The “Clear Day” show seems to falter only in a series of flower still lifes, which are more direct, lacking the deft sense of otherworldliness and isolation that can be found in the cottage canvases.

Maureen Gallace, “Summer House/Dunes,” oil on panel, 2009 (courtesy 303 Gallery)

Arranged at eye level across several galleries at PS1, one after another in a nearly endless display that disorients visitors’ sense of place, the paintings evoke the phenomenal still lifes of Italian master Giorgio Morandi, which featured bottles, pitchers, bowls, and other common objects. In addition to Morandi, Gallace has also cited Fairfield Porter, Edward Hopper, Jane Freilicher, Albert York, Agnes Martin, and Robert Ryman as influences. In a short 2009 piece for Travel & Leisure magazine, “An Artist’s New England,” Gallace wrote of Truro, in Cape Cod, “Part of the reason I love Truro is that Edward Hopper lived here. His work has been a big influence on mine. His landscapes are so beautifully painted and are so much about the essence of the places he depicts.” As with her description of Cézanne’s works, she could be talking about her own paintings, which are beautiful indeed, and transport viewers to another place. “The house doesn’t mean anything per se. It’s an empty vessel,” she told Elle Décor in 2010, when she was part of the 2010 Whitney Biennial. Gallace skillfully imbues these empty vessels with a kind of psychological mystery, leaving it up to each viewer to come up with their own private narrative.